Six things you need to know about the International Booker Prize 2023 shortlist

As the International Booker Prize 2023 shortlist is announced, discover the most interesting facts and trends that have emerged in this year’s selection

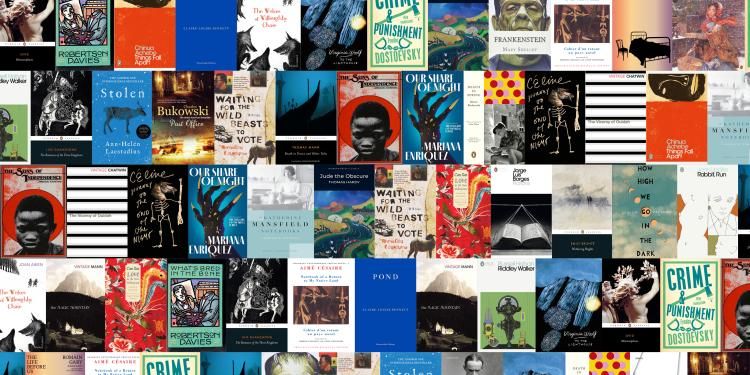

We asked each of our shortlisted authors and translators which three works of fiction have inspired them and their careers the most. Here’s what they said…

Romance of the Three Kingdoms by Luo Guanzhong

I read this book so many times when I was in school! I don’t remember any other reading experience that was so powerful and overwhelming. I can’t pretend to understand how this book affected my consciousness and sensibilities, but I can’t deny this book’s literary influence on me as a fiction writer, many years later.

Rabbit, Run by John Updike

Before this, the books I read when I was young followed remarkable lives. Stories about adventure and romance, hardship and adversity, struggle and triumph. What I realised when I read this novel at 18 was that, for the most part, not much happens in life. And while that truth was very disappointing, it was also oddly a relief.

Post Office by Charles Bukowski

I was already middle-aged when I read this book for the first time. I read it at a very difficult time, personally. Chinaski, the weary protagonist, is also going through a hard time. Strangely, though, I felt happy while I was reading it. Setting aside its literary significance, it was because I felt I would be able to bear it all, no matter how difficult, if I could look at the world through Bukowski’s eyes - if I could arm myself with Bukowski’s gaze to stand up against the world - and be accompanied by alcohol, too.

Cheon Myeong-kwan

Right now, I can’t stop thinking about a few books I read this month…

Our Share of Night by Mariana Enriquez, translated by Megan McDowell

For its elegant depiction of horrific violence and the different ways dialogue was handled.

Stolen by Ann-Helén Laestadius, translated by Rachel Wilson-Broyles

For its exploration of trauma and its visceral depiction of the differences between Swedish and Sámi languages and cultures in a third language (English).

How High We Go in the Dark by Sequoia Nagamatsu

For its lyrical depiction of grief and loss and its interlocking narrative structure.

Chi-young Kim

Wuthering Heights by Emily Brontë

Brontë touched my heart and mind when I was a child in Guadeloupe thus proving the force and magic of literature. Consequently, I adapted it into a Caribbean setting under the title La Migration des coeurs in French and Windward Heights in English.

Jude the Obscure by Thomas Hardy

For the same reasons as above.

Things Fall Apart by Chinua Achebe

Because it was the first book I read on the ravages of colonisation.

Maryse Condé

© P. Matsas Leemage- Hollandse HoogteTo the Lighthouse by Virginia Woolf

Because she inspired me to translate Maryse Condé’s novel Crossing the Mangrove.

The Viceroy of Ouidah by Bruce Chatwin

Because he inspired me to translate Maryse Condé’s novel The Last of the African Kings.

Cahier d’un retour au pays natal/Notebook of a Return to My Native Land by Aimé Césaire

Because he inspired me to translate Black Skin, White Masks and The Wretched of the Earth by Frantz Fanon.

Richard Philcox

Les soleils des indépendances/The Suns of Independence by Amadou Kourouma

Voyage au bout de la nuit/Journey to the End of the Night by Céline

La vie devant soi/The Life Before Us by Romain Gary/Emil Ajar

These are my fundamental fictions, the ones that pushed me to write. These three novels are alike in one thing: their reinvention of language! These authors made me understand that your mind will always revel in the beauty of language. To make the substance understood, the style matters above all. A fiction without style is a simple dissertation, destined for university libraries, not bookshops. However, the destiny of fiction is to touch everyone, without the distinction of education, in the name of language and style, in the name of beauty and delight.

GauZ’

© DMAn impossible question, but I’ll give it a try:

Riddley Walker by Russell Hoban

The novel that first exploded in my mind with the possibility of language, sound, music and emotion was Riddley Walker, the towering, poignant apocalyptic vision of the late, great Russell Hoban.

Waiting for the Wild Beasts to Vote by Ahmadou Kourouma

Many books have marked my career as a translator, but perhaps the most important is Waiting for the Wild Beasts to Vote by Ahmadou Kourouma, a brilliant, biting satire of post-colonial Africa that marries an oral tradition as old as time itself with a warmth, a wit and a savage power that can evoke a whole world and reshape it in the conjuring.

Love in the New Millennium by Can Xue, translated by Annelise Finegan Wasmoen

More recently, Can Xue’s Love in the New Millennium (translated by Annelise Finegan Wasmoen) was among a series of novels (including Sayaka Murata’s Convenience Store Woman, translated by Ginny Tapley Takemori, and Olga Tokarczuk’s Flights, translated by Jennifer Croft) that burst into my consciousness and forced me to rethink everything I thought I knew about literature. That is the real power of stories, and the true greatness of translation.

Frank Wynne

© Nick BradshawThe Little Match Girl by Hans Christian Andersen

This was the first Andersen story I read on my own, and the magnifying glass of the tears through which I opened that story each time. I don’t trust writers or storytellers who haven’t cried when reading that story. Over the theme of death and childhood there. I think it influenced my writing afterwards – as well as my character Gaustine, who says, ‘There is only childhood and death, and nothing in between.’

The Magic Mountain by Thomas Mann

This work is key to Time Shelter and to the theme of time and memory in general: and Borges’ Funes the Memorious. I find Mann increasingly important, a kind of Einstein of literary and historical time.

Fictions by Jorge Luis Borges

With Borges’ Funes the Memorious you get the private hell of memory, though I’ve always dreamed of having such a super-memory for all perishable things, a memory of clouds and dogs at three in the afternoon.

Georgi Gospodinov

© Phelia BaruhCrime and Punishment by Fyodor Dostoevsky

Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment blew my angsty teen mind – it was one of the first novels in translation I ever read (although I didn’t really register this fact at the time). Dostoevsky inspired me to start studying Russian, which led to Slavic linguistics, which eventually led me to Bulgarian… I reread it regularly every five years or so (in different translations, my Russian is too rusty for the original at this point) and can happily report that I have yet to be disenchanted.

Death in Venice by Thomas Mann

This book, which I first read in English and then reread shortly thereafter in German, was the first work to give me a taste of translation’s magical energy, showing the way a translation recreates an atmosphere, capturing the shades and hues of the language and a world.

What’s Bred in the Bone by Robertson Davies

More generally, my all-time favorite writer is the Canadian novelist Robertson Davies – I can only hope my translations might someday approach in some small way his witty and brilliant use of English. It turns out he was shortlisted for the Booker in 1986… inspiring company to aspire to!

Angela Rodel

La vie devant soi/The Life Before Us by Romain Gary/Emil Ajar

Because of its ironic and humorous way of criticising racism in French society and its beautiful description of how it feels to be a migrant child.

Los recuerdos del porvenir/Recollections of Things to Come by Elena Garro

Because it allowed me to see that my country is indeed a magical place.

Suicidos ejemplares/Model Suicides by Enrique Vila-Matas

Because it made me understand that the ‘short story’ is a major genre.

Guadalupe Nettel

The Wolves of Willoughby Chase by Joan Aiken

Frankenstein by Mary Shelley

Pond by Claire-Louise Bennett

My career comes from a love of reading, and so I’ll list three books that have meant a lot to me over the years: a book I loved as a child – The Wolves of Willoughby Chase by Joan Aiken; a book I read in my twenties and which I suspect I will return to many times over the years: Frankenstein by Mary Shelley; and a book that blew me away as an adult: Pond by Claire-Louise Bennett.

Rosalind Harvey

Death in Spring by Mercè Rodoreda

Death in Spring is a celebration, a wonderful bacchanalia dedicated to life, literature, the impossible, and the wild, mysterious nature of that untouchable thing we call imagination. What is untouchable? With every phrase, every comma and every full-stop, Mercè Rodoreda places it beneath your eyes and nose, warm, vibrant and unobstructed. It leaves me drunk. Sick with happiness, beauty, and passion.

The Katherine Mansfield Notebooks by Katherine Mansfield

If my bedroom is a monastic cell, Mansfield’s diaries rest on the bedside table like a bible. To me, Katherine Mansfield is the how. How she says what she says is the enigma of beauty. When I feel I’m not writing well, I stop writing. And I read Mansfield’s diaries.

Metamorphoses by Ovid

Ovid’s Metamorphoses is grounded in Greco-Roman tradition, which is in large part also my tradition. They’re a game, a poetic game that is incredibly baroque and fun, luxurious and filled with images that nourish and awaken my subconscious. Rereading Ovid means connecting with that subconscious, opening the doors to goddesses and monsters, to a natural world that is at once divine and human, bound. Ovid is inexhaustible, inspiring.

Eva Baltasar

Reading the work of two Jameses – Baldwin and Kelman – blew the top of my head off. Writing by Kate Briggs, Sawako Nakayasu, Don Mee Choi, Lina Mounzer and so many others on translation has provided steady, generative company. But most of all, closely reading and translating Eva Baltasar, Claudia Hernández, Susana Moreira Marques, Mariana Oliver and Geovani Martins, as well as all the other authors I’ve had the pleasure to work with, has informed and changed my practice; each experience taught me an invaluable lesson about how to engage with and write literature in translation.

Julia Sanches

© Dagan Farancz