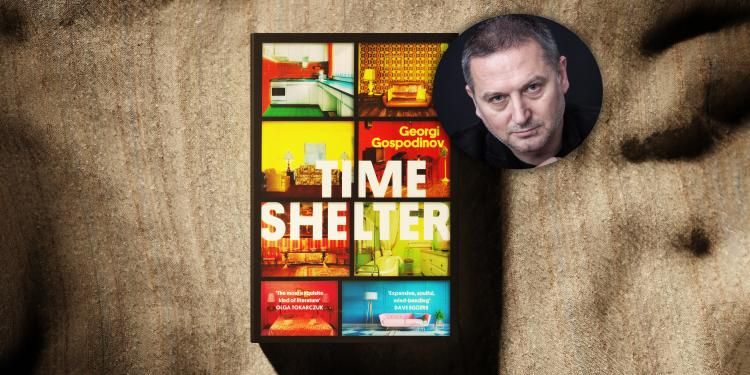

Angela Rodel interview: ‘Translators don’t play second fiddle to authors, it’s like a duet’

The winner of the International Booker Prize 2023, translator Angela Rodel talks about the inspiration behind Time Shelter in an exclusive interview

The author of Time Shelter, now the winner of the International Booker Prize 2023, talks about populism, Brexit, nostalgia – and his grandmother’s stories

Read interviews with all of the International Booker Prize 2023 authors and translators here.

How does it feel to be shortlisted for the International Booker Prize 2023, and what would winning mean to you?

I was happy, as were many people in Bulgaria. It turns out that Time Shelter is the first book written in Bulgarian to be nominated for the [International] Booker. This encourages writers not only from my country, but also from the Balkans, who often feel themselves outside the sphere of English-speaking attention. It is commonly assumed that ‘big themes’ are reserved for ‘big literatures’, or literatures written in big languages, while small language, somehow by default, are left with the local and the exotic. Awards like the International Booker Prize are changing that status quo, and this is very important. I think every language has the capacity to tell the story of the world and the story of an individual person. If my novel, Time Shelter, wins, I will know that its anxieties and forebodings have been understood.

What were the inspirations behind the book? What made you want to tell this particular story?

My urge to write this book came from the sense that something had gone awry in the clockworks of time. You could catch the scent of anxiety hanging in the air, you could touch it with your finger. After 2016 we seemed to be living in another world and another time. The world’s disintegration with the encroachment of populism and playing the card of the ‘great past’ in the US and in Europe provoked me. Brexit was the other trigger. I come from a system that sold a ‘bright future’ under communism. Now the stakes have shifted, and populists are selling a ‘bright past’. I know via my own skin that both cheques bounce, they are backed by nothing. And that’s why I wanted to tell this story about the ‘referendums on the past’, undertaken by every European country. How does one live with a deficit of meaning and future? What do we do when the pandemic of the past engulfs us? The last chapter of the novel describes how the past comes to life: the troops and tanks amassed to reenact the beginning of World War II unexpectedly invade the neighbouring country’s territory. The novel was published in Bulgarian in 2020.

How long did it take to write the book, and what does your writing process look like? Do you type or write in longhand? Are there multiple drafts or sudden bursts of activity? Is the plot and structure intricately mapped out in advance?

The idea for my character Gaustine, who establishes ‘clinics of the past’ to create protected time for people losing their memory, came to me 15 years ago. In the last six or seven years, I’ve come to realise the past can be a ‘discrete monster’ and its collective return is not at all innocent. During this period, I started doing lots of research – I had a year-long fellowship at the New York Library’s Cullman Center. The writing process itself took me nearly three years. I always scribble the first draft or notes in a notebook, and only then type them up on the computer. As it happens, I always end up with seven drafts of my novels. The idea of going from the clinics of the past, which deal with patients’/residents’ private pasts, to European referendums on the past was the basic framework for the plot from the outset. But I’m the kind of writer who likes to follow language and the stories themselves. I think language is smarter than we are. I come from poetry, so every word is precious to me. I write my novels sentence by sentence. And if I can get to the point where I’m following the narrator’s voice, with its language and rhythm, and even sometimes surprising myself with the way the story is unfolding, that’s good for the book. I don’t like novels written like the Periodic Table, where the writer knows from the start what’s going to be in each box. I want the story to excite me, to be natural and human, not going from point A to point B, but instead getting lost and found. Besides, a novel about the loss of memory (both personal and collective) couldn’t be otherwise.

I’m always suspicious of translators who have no questions about the text

Where do you write? What does your working space look like?

At the very beginning, when I’m writing in my notebook, I can be anywhere. It might seem strange to see someone using a notebook and surreptitiously jotting down thoughts in some random place, in the afternoon. I love afternoons. Then, when it comes to the real writing, I prefer to be in the same place, for it to be morning and to be alone. I never managed to get a ‘room of my own’, so I write in the living room when my family isn’t there. I used to smoke a lot, but I don’t anymore, I’ve found that if the story grabs hold of you, you don’t need anything else around you: coffee, cigarettes, nuts. Your only goal is to not lose the flow of the language.

What was the experience of working with the book’s translator, Angela Rodel, like? How closely did you work together on the English edition? Did you offer any specific guidance or advice? Were there any surprising moments during your collaboration, or joyful moments, or challenges?

I love working directly with my translators, getting their questions and answering them. I’m always suspicious of translators who have no questions about the text. I know I’ve left a lot of traps in my writing; references, quotes, allusions. As an author for whom language itself is paramount, I suspect my books are not at all easy to translate. I think Angela Rodel did truly impressive work with her translation, because she often had to translate not only the text itself, but the context of all the stories inside the novel. The novel plays with the reenactment of different decades of the twentieth century, and there are many subtle places where the slang of a given era must also ring true. In this new construction of the past, different layers of language and memory are activated. How can the past be translated at all, personally and collectively? And how can nationalist kitsch be translated for the different countries in the novel?

I recall that English was happily indulgent towards the title, which is a neologism. In French, Spanish and Danish the play on ‘bomb shelter’ didn’t work as well. Another problem was with the direct speech, which in the original is not marked as direct speech. In Bulgarian it’s somewhat easier to follow, but in English not so much. We also had a long discussion with the editor about whether to mark speech with quotation marks or follow the logic of the original. We decided to risk it, hence Angela had the difficult task of translating the two voices – Gaustin’s and the narrator’s, which run in parallel, like two threads, intertwining and separating. This blending and diverging of voices is logically important to the novel, so I’m glad we kept the original approach to the speech.

Why do you feel it’s important for us to celebrate translated fiction?

Let me put it simply. When we have ears and eyes (and a translation) for the story of the Other, when we hear and read it, they become a person like us. Storytelling generates empathy. It saves the world. Especially a world like the one we live in today. We write to postpone the end of the world. And the end of the world is a very personal thing. It happens in different languages. Translation gives us the sense that we are working towards this postponement together. It gives us the sense that in my Bulgarian story of sadness and anxiety, in someone else’s Peruvian story, for example, and in your English story, we are hurting in a very similar, human way. There is no other way to tame that pain and respond to it than to tell it. And the more languages we tell it in, the better.

If you had to choose three works of fiction that have inspired your career the most, what would they be and why?

My grandmother’s stories that I listened to as a child. Stories that blended fiction and reality, with no clear end to one and beginning to another. Stories that had voices and whispers, and miracles at the end. Plus, the characters lived in the same village as us. Then there was the first Andersen story I read on my own, ‘The Little Match Girl’, and the magnifying glass of the tears through which I opened that story each time. I don’t trust writers or storytellers who haven’t cried when reading that story. Over the theme of death and childhood there. I think it influenced my writing afterwards – as well as my character Gaustine, who says, ‘There is only childhood and death, and nothing in between.’ And third, I’ll point to two works that are key to Time Shelter and to the theme of time and memory in general: Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain and Borges’ Funes the Memorious. I find Mann increasingly important, a kind of Einstein of literary and historical time. Whereas with Borges, you get the private hell of memory, though I’ve always dreamed of having such a super-memory for all perishable things, a memory of clouds and dogs at three in the afternoon.

Angela Rodel