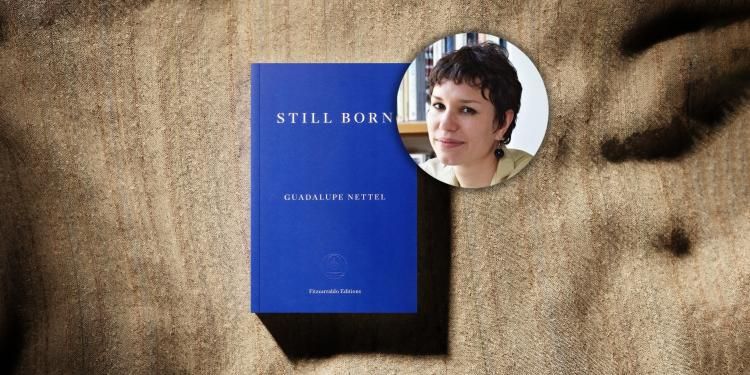

Guadalupe Nettel interview: 'Many demands weigh on mothers'

Shortlisted for the International Booker Prize 2023, author Guadalupe Nettel talks about the inspiration behind Still Born in an exclusive interview

With Still Born shortlisted for the International Booker Prize 2023, its translator talks about settling on the book’s title – and why literary translation should be seen as a profession rather than a labour of love

Read interviews with all of the International Booker Prize 2023 authors and translators here.

How does it feel to be shortlisted for the International Booker Prize 2023 – an award which recognises the art of translation in such a way that the translators and author share the prize money equally should they win – and what would winning the prize mean to you?

It feels lovely and a little surreal, and I am incredibly honoured and very pleased for Guadalupe [Nettel] and the book, too. To be honest I can’t really imagine winning, and there are so many other good books on the longlist that I would be happy to see win. I feel a little conflicted about prizes in general (while recognising that they can bring much-needed attention to some books) because so many excellent books don’t win, or even get nominated, for a lot of the excellent prizes out there; but having said that, any book that wins the IBP would mean a huge amount not just to the author, translator and publisher, but also to translated fiction in general – the more attention that is placed on to books not written in English, the better, and this prize does a wonderful job of placing such attention on books from elsewhere.

How long did it take to translate Still Born, and what does your working process look like? Do you read the book multiple times first? Do you translate it in the order it’s written?

It’s always hard for me to say how long it takes to translate a book, because I don’t ever work solely on a translation - like most literary translators, I combine translating books with other, more stable work. For me that means teaching, running workshops and mentoring, and the translation takes place in the spaces between all that other work. But if I were to hazard a guess, I’d say perhaps four or five months if I were doing it full-time. Although that could be wildly off! I do generally work on a book in the order it’s written. I’d already done a sample of the book for Guadalupe’s agent to pitch around, so I had a sense of the style, but I’ve never read a book multiple times before starting work. Although, once you’ve finished working on a translation, you will have definitely read it several times over, and in a very particular, obsessive, closely-focussed way. It’s like living inside it for a few months, which is such a privilege.

What was the experience of working with Guadalupe Nettel like? How closely did you work together? Was it a very collaborative process? Were there any surprising moments during your collaboration, or joyful moments, or challenges?

I’ve been lucky enough to always have relatively collaborative relationships with authors, and if they are happy to answer questions and thrash ideas around then that’s my preferred way of working. I’m never sure if working on a book by a dead author who you can’t ask anything would be terrifying or liberating! Guadalupe and I had some moments of disagreement (for example around the title, which is such a crucial aspect of any book, although we did finally end up on the same page) but ultimately we worked together very well with the invaluable help of Tamara, our brilliant editor, and I think the result shows that that kind of collaboration always brings the best out in a book.

Rosalind Harvey

I’m never sure if working on a book by a dead author who you can’t ask anything would be terrifying or liberating!

Aside from the book, what other writing did you draw inspiration from for your translation?

I’d worked on another book of Guadalupe’s before, and a few stories, so I think that helps in terms of the translation – you already have a feel for the way an author uses language and how they pull voices and stories together. There are a lot of brilliant books about similar topics coming out of Latin America at the moment, although they’re not really stylistically similar, I would say, but I was certainly thinking of Jazmina’s Barrera’s Linea Nigra (translated by Christina MacSweeney), and work by Samanta Schweblin and Mónica Ojeda, as I worked (there’s a great piece about this wave of women’s writing by Veronica Esposito in World Literature Today, here). These books form a constellation, you might say, of new and vital writing about women’s lives, bodies and experiences.

What was your path to becoming a translator of literary fiction? What would you say to someone who is considering such a career for themselves?

I did a degree in Hispanic Studies and then worked as a bookseller for a couple of years before doing an MA in literary translation at the University of East Anglia, and I also took part in a literary translation summer school run by the British Centre for Literary Translation, which is where I met the woman who went on to become my friend and mentor, Anne McLean. Anne is a wonderful translator of Latin American fiction, and an incredibly generous, playful person, and she and I worked on some short stories and then novels together. It was a really practical apprenticeship where I learned not only how to edit, how to deal with editors, and how to think about what kind of English you’re working towards, but was also introduced to publishers and agents at book fairs and just generally how the world of translated lit works.

In terms of a career, though, it is wildly unpredictable and not particularly stable, so I always say to people thinking about getting started to not give up the day job (unless you are independently wealthy) and to be mindful of how much speculative work you have time/energy for. I think it’s also important to stress that, like anything in the arts, while it is clearly a job that involves a lot of passion and love, it is still a job, and that means asking for and expecting fair payment and not working for free. Viewing it as a profession rather than a labour of love allows us all to survive a bit better, and also means literary translation as a whole is a little more sustainable and (ideally) might become more diverse than it currently is.

Why do you feel it’s important for us to celebrate translated fiction?

For the same reason it’s important to celebrate any fiction we think is worth reading – the separation of ’translated fiction’ from so-called ‘original fiction’ is a false and unhelpful one, I feel, both for authors and for readers (not to mention publishers!), and just generally for the health of the literary ecosystem, and we would all do well to just follow our interests and our obsessions, and read whatever book we feel drawn to, no matter where it comes from or which stage of the mediation process it happens to be at.

If you had to choose three works of fiction that have inspired your career the most, what would they be and why?

My career comes from a love of reading, and so I’ll list three books that have meant a lot to me over the years: a book I loved as a child –The Wolves of Willoughby Chase by Joan Aiken; a book I read in my twenties and which I suspect I will return to many times over the years: Frankenstein by Mary Shelley; and a book that blew me away as an adult: Pond by Claire-Louise Bennett.

Guadalupe Nettel

© Germán Nájera