Rosalind Harvey interview: 'The separation of translated fiction from so-called original fiction is false'

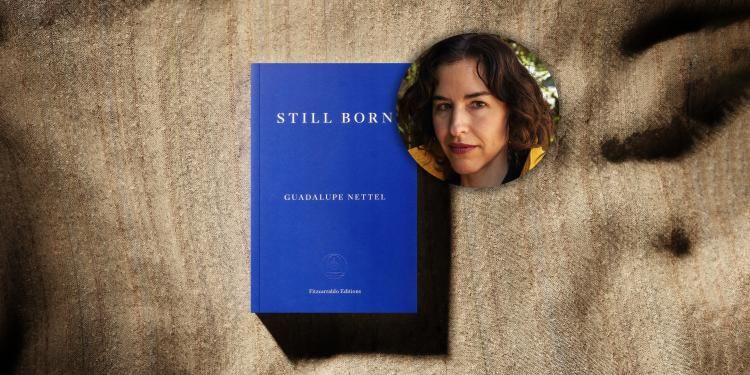

Shortlisted for the International Booker Prize 2023, Rosaline Harvey talks about her translation of Still Born in an exclusive interview

With Still Born shortlisted for the International Booker Prize 2023, the author talks about challenging patriarchal ideas of motherhood and telling her friend’s inspiring story

Read interviews with all of the International Booker Prize 2023 authors and translators here.

How does it feel to be shortlisted for the International Booker Prize 2023, and what would winning mean to you?

It is a great joy. I see it as a wonderful opportunity for this novel to reach more readers, not only in the UK but around the world. For me, winning the International Booker Prize would be a dream come true.

What were the inspirations behind Still Born? What made you want to tell this particular story?

In the beginning, my intention was to write the story of my friend and her little daughter, which I’ve found incredibly inspiring, both terrible and beautiful at the same time. Every day, children are born with neurological conditions that set them apart from others. Their families often take these situations as misfortunes that will end forever the life they had and turn it into hell. I wanted to show, through the story of this friend of mine, that it is possible to transform this painful experience into a meaningful one.

Many demands weigh on mothers. They are always compared to an unattainable stereotype, one that has made women feel inadequate. Not to mention those who decide to remain childless, who are rarely represented in literature up to now. To me, Still Born is a novel which affirms female choices and which challenges patriarchal ideas of motherhood and maternal instinct.

I would like this novel to help readers realise that human diversity – especially that of children with neurological conditions and women of all kinds – is always beautiful and interesting and that there is no reason to fear or reject it.

How long did it take to write Still Born, and what does your writing process look like? Do you type or write in longhand? Are there multiple drafts or sudden bursts of activity? Is the plot and structure intricately mapped out in advance?

I always write in a mix of ways, sometimes by hand and sometimes on the computer, and each of my books has several drafts. This novel in particular started as a series of interviews with my friend on whom the story is based. Those interviews became a text. The other stories, that of Doris and Nicolás for example, are fiction and I wrote them to accompany the main story, to give it air and to be in dialogue with it. It took me about three years to write Still Born. At first, I thought it would be a novella and I had quite a clear idea of its structure, but then the story grew beyond what I had expected, and I wrote the second part that sheds light and adds meaning to the first. The writing of it was much more intuitive.

Guadalupe Nettel

© Germán NájeraMore than journalism or anthropological studies, [translated fiction] allows us to connect beyond ideologies, and to enter into a space of intimacy with people from other nations

Where do you write? What does your working space look like?

In many places. My studio is actually an open room in my house, and I can really concentrate only when no one is at home. That’s why I often leave early and settle down in a café, or take a few days out of town in a quiet place where I can disconnect from everything. For the writing of this novel I accepted a short residence near Venice offered by Ca’ Foscari University, and this really helped me to finish the book.

What was the experience of working with the book’s translator, Rosalind Harvey, like? How closely did you work together on the English edition? Did you offer any specific guidance or advice? Were there any surprising moments during your collaboration, or joyful moments, or challenges?

Rosalind and I have worked together on several projects and I think she is a very talented translator, definitely one of the best. I’m glad that she is receiving this recognition. She deserves all the prizes.

Why do you feel it’s important for us to celebrate translated fiction?

Because fiction is the most powerful vehicle of empathy that I know.

More than journalism or anthropological studies, it allows us to connect beyond ideologies, and to enter into a space of intimacy with people from other nations. It makes us share their fears, their hopes, and their life experiences.

If you had to choose three works of fiction that have inspired your career the most, what would they be and why?

La vie devant soi by Emil Ajar, because of its ironic and humorous way of criticising racism in French society and its beautiful description of how it feels to be a migrant child.

Los recuerdos del porvenir by Elena Garro, because it allowed me to see that my country is indeed a magical place.

Suicidos ejemplares by Enrique Vila-Matas, because it made me understand that the ‘short story’ is a major genre.

Rosalind Harvey