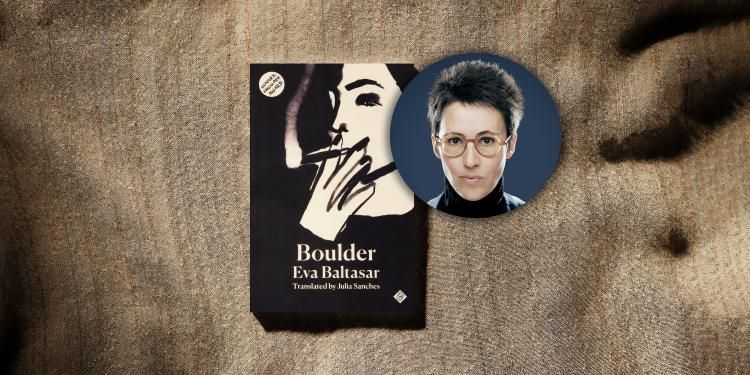

Julia Sanches interview: 'The mythical English reader is just that, a myth'

Shortlisted for the International Booker Prize 2023, Julia Sanches talks about the inspiration behind Boulder in an exclusive interview

With Boulder shortlisted for the International Booker Prize 2023, its author talks about needing to be in love with her characters and why her writing space resembles a monastic cell

Read interviews with all of the International Booker Prize 2023 authors and translators here.

How does it feel to be shortlisted for the International Booker Prize 2023, and what would winning mean to you?

Like joy and surprise invited themselves over for lunch and are still sitting here at the table, keeping me company. The gratitude I felt at first for everyone who helped get Boulder on the longlist has grown and seems to want to encompass even more people: editors, translators, and writers I’ve read and loved. Living and dead. Gratitude is whole and strives to last a lifetime.

Winning the International Booker Prize would mean seeing the moves I choreographed in the privacy of a garden suddenly on display in a ballroom. I’d like to think that all the lights glowing in the chandelier will warm my hands, feet and heart so I can dance better and longer.

What were the inspirations behind the book? What made you want to tell this particular story?

My protagonists are mirror images of myself, only more precise and always veiled. I try to discover who they are by writing, travelling to their darkest, most uncomfortable corners, which is like travelling to the darkest corners of myself, corners that are often repressed and at times denied wholesale. Being able to embark on this journey aboard a novel is as exciting as it is unsettling. It’s as if the novel had transformed into a caravel and the seas were vast but finite, teeming with monsters on the edge of the earth.

I was driven to write Boulder because I was fixated on the idea of getting to know a woman, through literature, who could embody a boulder; a woman like that isolated, solitary rock; a living metaphor at the mercy of the elements and weather, with cracks that allowed me to dig into her and uncover the secret hardness inside.

How long did it take to write the book, and what does your writing process look like? Do you type or write in longhand? Are there multiple drafts or sudden bursts of activity? Is the plot and structure intricately mapped out in advance?

I wrote three Boulders. Three different novels with the same title and the same intention: portraying a boulder-like character. The title came first; that word was what inspired me. The first and second iterations of Boulder were a struggle, the product of two and a half years of constant writing. I tried to create a character, to be the hand that shapes the soul and maps out a story for the body. But I wasn’t in love with those two characters, who were completely different from each other. I need to want to be with my characters, meet them again every day, be in their company when I reread the novel, and love them through language, which is the only way I have of touching them. But I couldn’t.

I deleted the two novels and spent a few months learning how to give in. The light-bulb moment, the moment of understanding, came when I realised I didn’t have to form a character so much as let the character show herself. I asked for an image that would spark the third Boulder, and what came to me was a memory: Myself at the age of 20 boarding a freighter on Chiloé island on a stormy night. It was as I wrote that memory that I found the voice for the third Boulder, the definitive one. For six months, the voice pulled me along; it was my compass, and I could have followed it with my eyes covered. I put all my strength and will at the service of language, so it would be language that shaped Boulder. I didn’t know where I was going. The novel ferried us both like a ship to a final port, and it was there, in that foreign land, that I understood I was in love.

Eva Baltasar

The room is uterine, interior, a place for maceration, like a cabin. The desk is small and black, just enough for a computer. There is a mirror on the wall; I talk to it while I write

Where do you write? What does your working space look like?

I write in my bedroom, which resembles a monastic cell. The only furniture is a desk, a chest of drawers, and a bed. In lieu of a cross, a Magritte tree. The room is uterine, interior, a place for maceration, like a cabin. The desk is small and black, just enough for a computer. There is a mirror on the wall; I talk to it while I write. There are hardly any other objects: a mug, dictionaries, a meditation bowl.

What was the experience of working with the book’s translator, Julia Sanches, like? How closely did you work together on the English edition? Did you offer any specific guidance or advice? Were there any surprising moments during your collaboration, or joyful moments, or challenges?

Working with Julia Sanches is a joy. Boulder isn’t the first novel of mine she’s translated, which means she knows me, my writing, and my terrain; she knows when the path is flat and when the dunes are variable, and she knows how to take up and translate the landscape of my writing, which in her hands becomes a shared space where the two of us meet. A translated novel is always a co-authorship, and I am lucky to share this with Julia Sanches. Just as I write in solitude, she translates in solitude, which is how she makes the work her own and adds her own authorship, that special, valuable ingredient. After this intense process, we meet and solve any questions that come up. Just knowing Julia is working on my writing, that my protagonist is in her hands, like a figurine she is teaching a new language to and prepping for a trip to another culture, is a reason for celebration.

Why do you feel it’s important for us to celebrate translated fiction?

Literature is art, it is human creation, and this makes it universal. The fact that translation can take literature outside the borders of its original language is a gift, and I believe gifts shouldn’t be ignored, that they come with an obligation. Celebrating translated fiction means celebrating the human capacity for courage and domestication: that we can take a work, mount it like a horse, and send it anywhere in the world as a messenger. Thanks to translation, the message is able to travel and not lose its way, to reach its destination and not be misunderstood; translation moves treasures from one place to another, expanding our heritage, leaving no one the poorer.

If you had to choose three works of fiction that have inspired your career the most, what would they be and why?

Ovid’s Metamorphoses. Ovid’s Metamorphoses is grounded in Greco-Roman tradition, which is in large part also my tradition. They’re a game, a poetic game that is incredibly baroque and fun, luxurious and filled with images that nourish and awaken my subconscious. Rereading Ovid means connecting with that subconscious, opening the doors to goddesses and monsters, to a natural world that is at once divine and human, bound. Ovid is inexhaustible, inspiring.

The Diaries of Katherine Mansfield. If my bedroom is a monastic cell, Mansfield’s diaries rest on the bedside table like a bible. To me, Katherine Mansfield is the how. How she says what she says is the enigma of beauty. When I feel I’m not writing well, I stop writing. And I read Mansfield’s diaries.

Mercè Rodoreda’s Death in Spring. Death in Spring is a celebration, a wonderful bacchanalia dedicated to life, literature, the impossible, and the wild, mysterious nature of that untouchable thing we call imagination. What is untouchable? With every phrase, every comma and every full-stop, Mercè Rodoreda places it beneath your eyes and nose, warm, vibrant and unobstructed. It leaves me drunk. Sick with happiness, beauty, and passion.

Julia Sanches