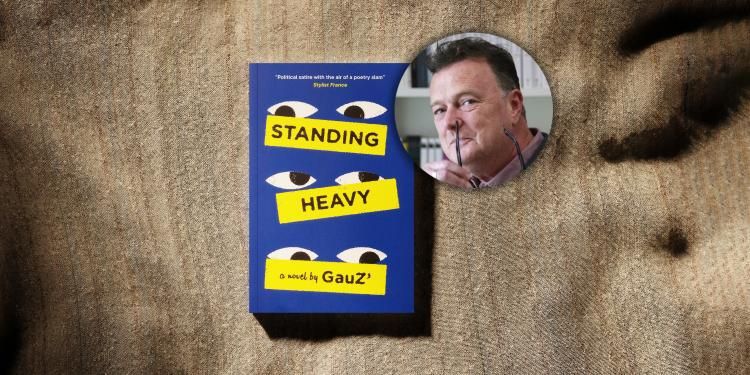

GauZ' interview: 'Africans never abandon laughter, no matter how serious the situation'

Shortlisted for the International Booker Prize 2023, GauZ’ talks about the inspiration behind his debut novel Standing Heavy in an exclusive interview

With Standing Heavy shortlisted for the International Booker Prize 2023, its translator talks about how his work allows him to be many different writers – and listening to West African music as part of his research

Read interviews with all of the International Booker Prize 2023 authors and translators here.

How does it feel to be shortlisted for the International Booker Prize 2023 – an award which recognises the art of translation in such a way that the translators and author share the prize money equally should they win - and what would winning the prize mean to you?

It’s hard to put into words how overjoyed I am to be shortlisted for the International Booker – especially for Standing Heavy, a book that is very dear to my heart.

How long did it take to translate the book, and what does your working process look like? Do you read the book multiple times first? Do you translate it in the order it’s written?

I always read a book at least once before beginning to translate - simply to enjoy it as any reader would. To laugh or cry or flinch as I respond to the story, the voice, the humour, the cadence of the text. Only then do I plunge in and begin to actually translate. I usually work through the book as written – and by the time I come to the end of a first draft, I can hear the various voices of characters in my head, and I can see the shape of the book as it will be in English.

What was the experience of working with the GauZ’ like? How closely did you work together? Was it a very collaborative process? Were there any surprising moments during your collaboration, or joyful moments, or challenges?

Collaborating with authors varies enormously from book to book. I will always have queries for an author – about word choices, about specific cultural or historic references. I usually get in touch with the author once I have finished a first draft. I enjoy talking through the way I have approached the translation. How authors respond varies enormously - some translations are more collaborative than others.

Aside from the book, what other writing did you draw inspiration from for your translation?

GauZ’s writing has echoes of the great Ivorian novelist Ahmadou Kourouma, whose late novels it was my honour to be able to translate. But GauZ’ also loves word play, punning and humour, and his voices sometimes echo the late novels of Romain Gary, one of my favourite French novelists. I re-read both while I was working on Standing Heavy, and I spent a lot of time listening to a spotify playlist of Ivoirian and West African music.

Frank Wynne

© Nick BradshawThe history of literature written in English (or indeed any language) bears the mark of all the translations that have fed into the rushing torrent of voices that make up our world

What was your path to becoming a translator of literary fiction? What would you say to someone who is considering such a career for themselves?

Like many people of my generation, I came to literary translation by happy accident. I had no idea what skills or qualifications would be required to undertake the glorious yet onerous task of bringing other voices, other stories into English. An editor once asked why I choose to translate rather than to write, and I said, because through the art of translation I can be many very different writers, tell stories I could never have imagined or written, inhabit worlds that are at once familiar and completely alien. Like any role in the arts, it can be poorly paid and hugely frustrating, but the reward of recreating a text, rediscovering a voice, is unlike any that I have known.

Why do you feel it’s important for us to celebrate translated fiction?

Since the dawn of language, human beings have told stories so that they can share their thoughts, their experience, their history, their culture. To my mind, literature in translation is the most powerful way of fostering empathy, of nurturing curiosity, of developing an understanding not only of others, but of ourselves. The history of literature written in English (or indeed any language) bears the mark of all the translations that have fed into the rushing torrent of voices that make up our world. How much poorer would we be without The Iliad, The Tale of Genji, without Don Quixote, without the poetry of Anna Akhmatova, the nightmare worlds of Kafka, the fever dreams of Bora Chung, the harrowing power and warmth of the novels of Mani Shankar Mukherjee. Literature, like music, expands to accommodate a multitude of voices, and celebrating those voices, those stories is, to me, the essence of what it means to be human.

If you had to choose three works of fiction that have inspired your career the most, what would they be and why?

An impossible question, but I’ll give it a try:

The novel that first exploded in my mind with the possibility of language, sound, music and emotion was Riddley Walker, the towering, poignant apocalyptic vision of the late, great Russell Hoban.

Many books have marked my career as a translator, but perhaps the most important is Waiting for the Wild Beasts to Vote by Ahmadou Kourouma, a brilliant, biting satire of post-colonial Africa that marries an oral tradition as old as time itself with a warmth, a wit and a savage power that can evoke a whole world and reshape it in the conjuring.

More recently, Can Xue’s Love in the New Millennium (translated by Annelise Finegan Wasmoen) was among a series of novels (including Sayaka Murata’s Convenience Store Woman, translated by Ginny Tapley Takemori, and Olga Tokarczuk’s Flights, translated by Jennifer Croft) that burst into my consciousness and forced me to rethink everything I thought I knew about literature. That is the real power of stories, and the true greatness of translation.

GauZ’

© DM