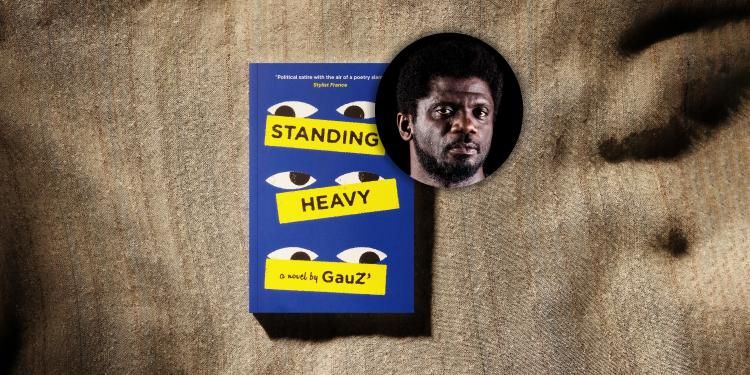

Frank Wynne interview: 'Literature in translation is a powerful way of fostering empathy'

Frank Wynne, translator of Standing Heavy which was shortlisted for the International Booker Prize 2023, talks to The Booker Prizes in an exclusive interview

With Standing Heavy shortlisted for the International Booker Prize 2023, its author talks about taking notes for his debut novel while working as a security guard – and how the world has been built on a succession of fictions

Read interviews with all of the International Booker Prize 2023 authors and translators here.

How does it feel to be shortlisted for the International Booker Prize 2023, and what would winning mean to you?

It is obvious for me to feel a great pride at my inclusion on the shortlist of the International Booker Prize. Especially for my first novel, the one that I think is the most stylistically and politically radical. In the West or elsewhere, when one is a security guard and African, one is made doubly invisible. Such a prestigious victory would be a tribute to all the invisible people in society, those who pedal down in the hold so that the upper decks may peacefully enjoy their champagne and their caviar.

What were the inspirations behind the book? What made you want to tell this particular story?

In this era of extreme capitalism which ever increasingly mocks humanity and nature just for the benefit of the ruling classes, just via the power of money, we need to put our eyes back in their sockets and understand the absolute absurdity of a consumerist society being the only model for life on earth. When I found myself working as a security guard during the sales in a department store in Paris, I immediately understood that this device was ideal for observing without being seen. I was at the very heart of the absurdity of the consumerist society. And as an African, I could finally be a ‘reverse ethnologist’, coolly describing the behaviour of those who had described us as entomologists describe ants. I gave it the distance of laughter, which Africans never abandon, no matter how serious the situation.

How long did it take to write the book, and what does your writing process look like? Do you type or write in longhand? Are there multiple drafts or sudden bursts of activity? Is the plot and structure intricately mapped out in advance?

In order to write this book, I began by taking notes while I was on duty. It’s a job where there’s nothing to do but watch. So it was ideal. After a few weeks, when I had enough money to buy a plane ticket, I returned to Abidjan where a post-election war was ending. There, I wanted to show that you could write l’histoire (with a capital H) and create les histoires (with a small H) without resorting to Kalashnikovs. This is how the idea of alternating a big story with small stories came to me. I had my notes from the Parisian shops and, even if they were funny, I had to find an original structure so as not to dilute them in a simple queue of anecdotes. I thought about this succession of generations of immigrants in Europe who had practised the profession of security guard in different political and geopolitical contexts. I had my structure (I’m obsessed with structure and language), I could begin.

Where do you write? What does your working space look like?

I don’t have a favourite place to write. Each of my novels is a particular adventure. For Standing Heavy, I needed geographic and critical perspective. I went to Ferkessédougou, a small town 600km from Abidjan, I settled down with Alberto (that was the name of my computer at the time) at the Tchologo Hotel, a somewhat outdated place, and I let my fingers run over the keyboard. For Comrade Papa, the main action took place in the 19th century. I moved to Grand-Bassam (where I still live), the first colonial capital of Ivory Coast. Alberto having passed away, it was with Gustavo that I worked listening to the murmur of the waves from the sandbank in the Gulf of Guinea. For Black Manoo, a book about marginalisation, I wrote mainly in a maquis, these open-air bars in Abidjan. For my last book, Cocoaïans, I wrote in Paris. I was stuck on a red sofa after a ruptured Achilles tendon while playing basketball with my son. I wrote all the time that my leg was in plaster. I don’t know yet where or how I’m going to write my next one. I only know it will be with Estrella, my new computer, because Gustavo died last year (may his microprocessors rest in peace!).

GauZ’

© DMWe need to put our eyes back in their sockets and understand the absolute absurdity of a consumerist society being the only model for life on earth

What was the experience of working with the book’s translator, Frank Wynne, like? How closely did you work together on the English edition? Did you offer any specific guidance or advice? Were there any surprising moments during your collaboration, or joyful moments, or challenges?

The role of translator is different from that of writer. I think that it is absolutely and totally necessary to leave the translator to his task. I am in favour of total freedom in his work. I can’t imagine anyone intervening in my work, so I return the favour. The freer we are, the better we are as creators. So I never intervene, I don’t interfere at all. Like in football or basketball, my role is to make the best assist possible, then trust the translator to put the ball in the back of the net and get the crowds going. Which is what Frank has done brilliantly. And the goal is for the whole team.

Why do you feel it’s important for us to celebrate translated fiction?

This world has been built on a succession of fictions. Capitalism, colonisation, war, nations, borders, justice, economy, etc. Everything is absolutely fiction. A fiction that has lasted for centuries, has had an enormous cost in human lives, in tragedies, in violence, in the destruction of nature… No theoretical or rhetorical arsenal can defeat a fiction. Only another fiction can do that. This is the great mistake of the Ancients who did not understand this. It is only by offering new, strong fictions that we can influence the mad race that is leading the world towards so much injustice and violence. Your role is essential in opening the door to these fictions that come from places that we would benefit from hearing from very loudly and much more often… they have a different fiction to offer the world.

If you had to choose three works of fiction that have inspired your career the most, what would they be and why?

Les soleils des indépendances by Amadou Kourouma; Voyage au bout de la nuit by Céline; La vie devant soi by Romain Gary… these are my fundamental fictions, the ones that pushed me to write. These three novels are alike in one thing: their reinvention of language! These authors made me understand that your mind will always revel in the beauty of language. To make the substance understood, the style matters above all. A fiction without style is a simple dissertation, destined for university libraries, not bookshops. However, the destiny of iction is to touch everyone, without the distinction of education, in the name of language and style, in the name of beauty and delight.

Frank Wynne

© Nick Bradshaw