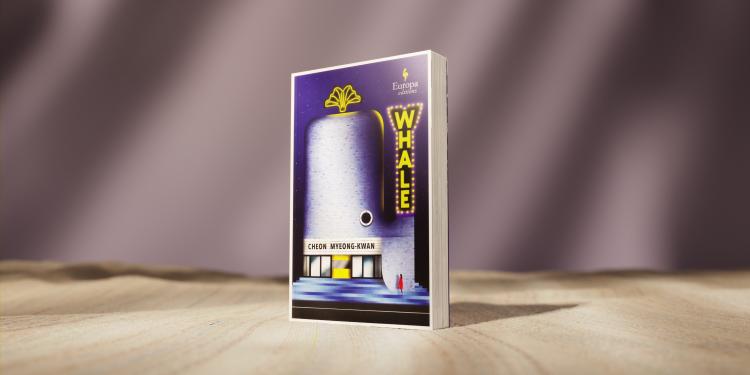

An extract from Whale by Cheon Myeong-kwan, translated by Chi-Young Kim

Whale, originally written in Korean, is shortlisted for the International Booker Prize 2023. Read an extract from the opening chapter here

Set in a remote village in South Korea, Whale follows the lives of three linked characters: Geumbok, an extremely ambitious woman who has been chasing an indescribable thrill ever since she first saw a whale crest in the ocean; her mute daughter, Chunhui, who communicates with elephants; and a one-eyed woman who controls honeybees with a whistle. A fiction that brims with surprises and wicked humour, from one of the most original voices in South Korea.

Chunhui—or Girl of Spring—was the name of the female brickmaker later celebrated as the Red Brick Queen upon being discovered by the architect of the grand theater. She was born one winter in a stable to a beggarwoman, as the war was winding down. She was already seven kilos when she emerged and plumped up to more than a hundred kilos by the time she turned fourteen. Unable to speak, she grew up isolated in her own world. She learned everything about brickmaking from Mun, her stepfather. When the inferno killed eight hundred souls, Chunhui was charged with arson, imprisoned, and tortured. After many long years in prison, she returned to the brickyard. She was twenty-seven.

In the heat of the summer day, Chunhui stood in the middle of the brickyard in her blue prison uniform, as the sun, closer now to the earth than it had been all year, scorched everything in sight. It was hot enough to melt cast iron. The pump in the middle of the yard had dried up long ago, leaving behind only a rusty stain on the ground where water had dripped down the metal pipe. Purslane, thistle, and foot-tall weeds had worked their way up through the hard, trampled earth and grown thick and tangled around the kilns. Daisy fleabane in particular had always crowded the perimeter of the brickyard like soldiers surrounding a fortress, and once the humans were gone the plant had instantly infiltrated the site, occupying the entire place. The brickyard consisted of only a few kilns, now ruined, built along a straight line, and a house woven together with wooden planks and shards of slate. The house had collapsed in Chunhui’s absence. Clumps of daisy fleabane bloomed among the ruins, while black lichen had overtaken the planks of wood that had once functioned as the floor of the house and the rippling slate roof. This was the law of nature.

Chunhui stood barefoot in the very yard in which she had played a lifetime ago. Next to the decrepit pump, the once luxuriant poplar tree had fallen and turned into a bare, rotting log, home to fat oyster mushrooms. The reek of sweat and the boisterous noise of the workers were gone, and Chunhui was the only one who’d returned, standing alone in the vast yard. Her eyes sought the scenes she had ached for during her journey back, but years of rain and wind had swept them all away. None of it remained anywhere in the brickyard.

Life is sweeping away the dust that keeps piling up.

That was what one of her cellmates, the one with freckles scattered across her face, always said. Everyone called her Cyanide—she had been sentenced to death for killing her two daughters and her husband with a cyanide-laced meal. Until the day she was executed, she was the one who swept and cleaned their cell. Any time the other prisoners grumbled, What’s the point of cleaning when your days are numbered? she would say, Life is sweeping away the dust that keeps piling up, as she mopped the floor with a rag, and sometimes she would add, Death is nothing more than dust piling up. Chunhui never quite understood what that meant, but that first day she was back, those riddles popped into her head as she walked toward the remnants of the house.

The sun blasted down on her and she stopped in her tracks, suddenly dizzy. The narrow path that led from the underpass below the train tracks to the brickyard, overtaken by weeds, had vanished from sight long ago. To get to the brickyard, Chunhui had trampled through the weeds, muddying her pants. With each step, blood oozed from her big toe, where the nail had ripped off, staining the parched red-clay ground. Children must have broken the bricks left behind in the brickyard, and now only shards were strewn about. Mosquito larvae squirmed in rain puddles formed just days before.

Cheon Myeong-kwan

She heard the train go by again, faintly. She was running after a white butterfly through a field of daisy fleabane. Grass pricked her bare calves. She wasn’t entirely sure whether she was dreaming or not.

Chunhui stepped onto the dusty maru. Foxtails poked through the broken floorboards. When she opened the door missing a hinge, the dark room smelled musty; wild animal excrement and something rotting. As her eyes adjusted to the dark, she saw dust-caked clothes and desiccated rats lying near the broken wardrobe. Black mold bloomed on the walls and torn wallpaper drooped gloomily from the ceiling. She looked around the room before heading into the kitchen, which was even more depressing with its blackened ceiling and walls. The shelves and the fireplace had both collapsed and the floor was damp with stale water. The cast-iron cauldron, which had always hung over the cookfire, was nowhere to be found, and only a dented nickel pot was upended on half-burned firewood where the hearth had once been. Chunhui’s nostrils flared as she imagined the smoky tang of fire and the savory smell of steaming rice, but all she could detect was dank mold. No warmth remained anywhere in the kitchen.

Chunhui opened the door to the yard and stepped outside. A passing train whistled in the distance. She walked toward the kilns. After she was taken away, people had pulled carts to the brickyard from neighboring villages to carry the abandoned bricks, using them to repair floors or hearths. Later still, children straggled here to play with the few remaining bricks. Nobody returned once all the usable bricks were gone. Only foxes and badgers circled at night, looking for food. Weeds thrived and dust blew in from the west and settled, erasing the many traces of human activity in the deserted brickyard.

Chunhui stepped inside a kiln, where it felt cool. Unlike the rest of the yard, not much had changed in the kiln. Though sunlight filtered through the gaps in the cratered walls, cool air circulated inside the dark cave of the kiln. She sat down and leaned against a wall. Her eyes closed in bliss when her sweaty back touched the cool wall. It was peaceful. Even the insects had fallen quiet, silenced by the unbearable heat.

The brickyard was overflowing with red bricks. She was running and playing among the piles. Her stepfather urged the men to work harder and her mother smiled flirtatiously at them, her face caked in makeup. A scene from a movie she once watched came back to her; she’d followed her mother into the theater. Gunfire rang out, hooves clattered, and blonde women screamed hysterically. She heard the prison guard who tormented her, whispering, Berkshire, a region in England famous for its pigs. She would never know what that word meant. After she bit off a chunk of his face, that guard had to wear an aluminum mask for the rest of his life. The hardships she had endured were too horrific to utter aloud, but that was all in the past now. Her suffering had dulled and now she was out of prison, back home in the brickyard.

She heard the train go by again, faintly. She was running after a white butterfly through a field of daisy fleabane. Grass pricked her bare calves. She wasn’t entirely sure whether she was dreaming or not. The butterfly fluttered farther and farther away, up into the sky.

The flames blazed red. The men shoveled coal into the kiln, sweat beading their thick, veiny forearms and their faces scarlet and shiny from the heat and light of the surging flames. With each shovelful of coal, black-red sparks burst up like flower petals. Chunhui was sitting in front of the kiln, staring at the blaze. Red and blue waves of fire turned the bricks crimson. Her face felt hot and it was hard to breathe, but she couldn’t move. The flames billowed and reached as if to swallow her; she would be sucked in and melt away. She wanted to get up and flee but couldn’t budge. It felt like a heavy boulder was pressing down on her. None of the workers gave her a second glance. She shouted at them, but only a small, odd moan squeaked out of her parched throat. Fire roiled in front of her nose until a large flame reared and then hurled itself at her. She sprang up.

She woke up and found herself soaked in sweat, her body radiating heat as if she were cattle mash. The sunlight that had been shining through the collapsed walls had shifted as she slept and was now blazing straight down on her face. Her throat was dry and her face felt hot. She tried to get up but was too weak. She crawled toward the shade. She wasn’t wearing any shoes, and the only clothing she had was the uniform on her back; the garments she had been wearing when she went into prison had disappeared during her lengthy stay. Out of breath, she closed her eyes and leaned against the wall.

Chi-Young Kim

Nine days earlier, Chunhui had walked out of prison and headed south, purely on instinct. Only when she found herself by the train tracks on the outskirts of the city that housed the prison did she realize she was heading to the brickyard. She continued along the tracks. When night fell she slept against a gravestone and when she grew hungry she drank from a creek in the valley below to sate herself. Sometimes she fished out salamander eggs floating in the cold water and at others she picked mulberries along the tracks. Blisters formed on her feet and then burst, revealing tender red flesh beneath. She threw off her shoes and walked barefoot. It was taxing to walk along the tracks in the hot summer sun, but she didn’t veer away; she didn’t want to come across anyone. When she neared a town, she left the tracks and skirted it.

On the third day, she tripped on a wooden support and tore the nail off her big toe. Reddish-black blood trickled out. She touched her foot on the hot tracks; the searing pain that shot from the tip of her foot through her whole body felt refreshing. She cooled off only when she got caught in a downpour, but her wet clothes plastered and twined around her, making it even more difficult to walk.

She headed south, slowly but doggedly. On the morning of the ninth day, she spotted the brick kilns lined up like matchboxes, beyond the tracks. Something hot pushed up from her empty stomach, choking her. Chunhui collapsed next to the tracks and looked down at the brickyard. She didn’t know what to do. She had just followed an instinctual drive to return; she hadn’t thought about what she would do once she made it there.

She looked over the other side of the tracks at Pyeongdae, far away, below the foot of the mountain. Cocooned by the morning fog, the town faintly revealed its shape, like a once-prosperous ancient city fallen into ruin. Even at a distance she could see the remnants of the movie theater looming up among the buildings, resembling a large whale breaching the surface for a breath. This whale-inspired theater had been designed by Geumbok, Chunhui’s mother. Chunhui could practically see the flashy theater signs and the crowds waiting to get in and the peddlers selling snacks—all of which had vanished when the theater burned down. Long, long ago, flames had engulfed the theater, the enormous blaze roaring up toward the sky with frightening force. Every last fire engine in the area had been mobilized, but they were unable to tame the raging flames. People watched helplessly as the theater burned, the theater built through one woman’s grit; the adjacent buildings went up in flames. This marked the end of Pyeongdae. While Chunhui was still in prison, people left this cursed, hopeless place, never to return. The train station was decommissioned. Pyeongdae, devoid of humanity, was now in the slow process of being erased, overtaken by nature.

Whale by Cheon Myeong-kwan

Read more about the author and translator

- By

- Cheon Myeong-kwan

- Translated by

- Chi-Young Kim

- Published by

- Europa Editions