Opinion

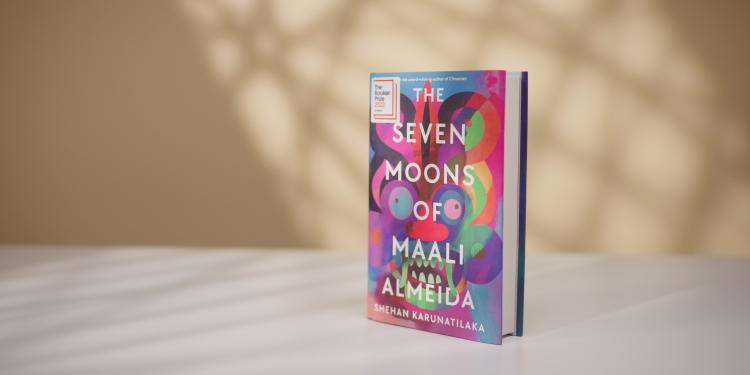

Explore Shehan Karunatilaka’s 2022 Booker Prize-winning novel The Seven Moons of Maali Almeida with your book club using our guide and discover why the judges said it was ‘full of ghosts, gags and a deep humanity’

Download a PDF of the reading guide for your book club

Colombo, 1990. Maali Almeida, war photographer, gambler and closet queen, has woken up dead in what seems like a celestial visa office. His dismembered body is sinking in the Beira Lake and he has no idea who killed him. At a time when scores are settled by death squads, suicide bombers and hired goons, the list of suspects is depressingly long. But even in the afterlife, time is running out for Maali. He has seven moons to try and contact the man and woman he loves most and lead them to a hidden cache of photos that will rock Sri Lanka.

Shehan Karunatilaka’s rip-roaring epic is a searing, mordantly funny satire set amid the murderous mayhem of a Sri Lanka beset by civil war.

The Seven Moons of Maali Almeida by Shehan Karunatilaka

Shehan Karunatilaka is considered one of Sri Lanka’s foremost authors. In addition to his novels, he has written rock songs, screenplays and travel stories.

Karunatilaka emerged on the world literary stage in 2011, when he won the Commonwealth Prize, the DSL and Gratiaen Prize for his debut novel, Chinaman. His songs, scripts and stories have been published in Rolling Stone, GQ and National Geographic.

Born in Galle, Sri Lanka, Karunatilaka grew up in Colombo, studied in New Zealand and has lived and worked in London, Amsterdam and Singapore. He currently lives in Sri Lanka.

Shehan Karunatilaka

© Deshan TennekoonIn a nutshell

Colombo, 1990: Maali Almeida is dead, and he’s as confused about how and why as you are. A Sri Lankan whodunnit and a race against time, Seven Moons is full of ghosts, gags and a deep humanity.

On the characters

Maali himself is the heart and (literally) soul of the book, and he’s wonderful company, cheerfully unapologetic about what others might see as his failings, and uncowed - even by his own sudden death - in his commitment to his violently chaotic country and to Jaki and DD, the loves of his complicated life.

On the book

This is Sri Lankan history as whodunnit, thriller, and existential fable teeming with the bolshiest of spirits.

The voice of the novel - a first-person narrative rendered, with an astonishingly light touch, in the second person - is unforgettable: beguiling, unsentimental, by turns tender and angry and always unsparingly droll.

Winner Shehan Karunatilaka with Booker Prize 2022 judges

© David Parry/Booker Prize FoundationThe TLS:

‘A rollicking magic-realist take on a recent bloody period in Sri Lankan history, set in an unpeaceful afterlife. It is messy and chaotic in all the best ways. It is also a pleasure to read: Karunatilaka writes with tinder-dry wit and an unfaltering ear for prose cadences.’

The Guardian:

‘Beneath the literary flourishes is a true and terrifying reality: the carnage of Sri Lanka’s civil wars. Karunatilaka has done artistic justice to a terrible period in his country’s history.’

The Hindu.com:

‘Karunatilaka increasingly raises questions of what you’re remembered as you die; what your love meant for those you left behind; and if it was all worth it in the end, to frequently moving effect.’

‘1989 was the darkest year in my memory, where there was an ethnic war, a Marxist uprising, a foreign military presence and state counter-terror squads. It was a time of assassinations, disappearances, bombs and corpses. But by the end of the 1990s, most of the antagonists were dead, so I felt safer writing about these ghosts, rather than those closer to the present.

‘I’ve no doubt many novels will be penned about Sri Lanka’s protests, petrol queues and fleeing Presidents. But even though there have been scattered incidents of violence, today’s economic hardship cannot be compared to the terror of 1989 or the horror of the 1983 anti-Tamil pogroms.’

Read more of Shehan Kurunatiaka’s interview on The Booker Prize website.

Shehan Karunatilaka

© Dominic SansoniThe Seven Moons of Maali Almeida is narrated entirely in the second person. Why might the author have chosen to write the novel in this manner? Does it enhance the reading experience?

The novel is set in 1990, against a backdrop of the real-life civil war that took place in Sri Lanka. At one point the protagonist writes a cheat sheet for an American journalist on the different factions in the war, which he signs off: Don’t try and look for the good guys, ‘cause there ain’t none. (p.22) Is Maali being reductive here? Do you think this is reflective of real life in Sri Lanka?

Seven Moons has been described as a cross-genre novel, merging magical realism with a ghost story, a whodunnit, and a state-of-the-nation piece of work. Discuss how Shehan Karunatilaka has allowed these genres to intersect and whether you think it is successful.

Maali’s character is complex. At the beginning of the novel we’re told: If you had a business card, this is what it would say. Maali Almeida. Photographer. Gambler. Slut. (p. 1). Yet despite his flaws, the Booker judges described him as ‘wonderful company’ and ‘cheerfully unapologetic about what others might see as his failings’. What is it about Maali’s character that makes him so likeable?

Karunatilaka has told the Booker Prize that ‘I spent most of my youth trying to write like Ondaatje, Rushdie and García Marquez… But the genius I have robbed from the most is of course Uncle Kurt [Vonnegut]’. To what extent are the influences of these writers visible in Seven Moons?

Despite being gay, Maali has an unusual relationship with a woman, Jaki. Jaki didn’t mind that you disappeared from parties, Jaki didn’t mind if you talked to boys, though she hated you talking to girls. And Jaki didn’t care if you didn’t touch her. (p. 58). What was the purpose of their relationship? Were there benefits for each, or was it one-sided?

‘Why is Sri Lanka Number One in suicides?’ asks the girl peering through thick glasses. ‘Are we that much sadder or violent than the rest of the world?’ ‘Who the fuck cares?’ says the hunched figure, as a lady in pigtails does her high jump over the edge. ‘It’s because we have just the right amount of education to understand that the world is cruel,’ says the schoolgirl. ‘And just enough corruption and inequality to feel powerless against it.’ (p.285) What might this excerpt from the text say about social conditions within Sri Lanka during the civil war, and why was the suicide rate in the country so high?

You were never claustrophobic despite all that time spent in bunkers and narrow beds and lifelong closets. But, like any reasonable person, you’d like the option of running away, especially when there is plenty to run from. (p. 140) Discuss what is meant by this quote, and how it relates to the way Maali was forced to live his life.

The book oscillates between real-life and an ‘in-between’ underworld, an afterlife that is as bureaucratic as the world above - laden with rules. Discuss why the author has subverted the idea that for many a better afterlife exists.

Seven Moons is laced with off-beat humour; the author adds levity to heavier moments. In an interview with The Booker Prize, he said, of Sri Lankans, ‘We specialise in gallows humour and make jokes in the face of our crises.’ Has the author succeeded in bringing the humour of his nation to life?

Maali Almeida’s final mission is to hold the tyrants at the heart of the Sri Lankan civil war accountable for their atrocities. Do you think he is successful? Is his parting body of work enough to instruct change?

The origins of the Sri Lankan Civil War predate its beginning in 1983.

The country was previously colonised by the British, who ruled it since 1815. At this point in time, the island was called Ceylon and when it gained its independence in 1948, a majority of Sinhalese (Buddhists) took power. There was also a minority of Tamils in the country at the time (comprised of Hindus and Christians), and the group subsequently found themselves marginalised.

In 1972, Ceylon is renamed Sri Lanka. At this point in time, The Tamil New Movement is formed, by V. Prabhakaran. While the group is mainly comprised of students, their campaign turns violent in 1975, when they assassinate the mayor of Jaffna.

In 1976, the Tamil New Movement joins with another Tamil group and forms the Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE). Other Tamil-led political groups emerge, and in 1976, a coalition called TULF proposes a separate Tamil State to be established in the north of Sri Lanka. Civil war formally breaks out in 1983, when tension between the groups culminates in 13 Sri Lankan soldiers being killed. Anti-Tamil riots begin, which result in massacres of the Tamil population, and thousands are killed.

The following decades are marked by radicalisation, suicide bombs, car bombs, civilian deaths, kidnapping, torture, displacement and assassinations between government forces and opposition sides. A long road to peace began in the early 2000s when Norway attempted to broker a peace deal, though violence continued.

In 2009, the Sri Lankan government declared victory, as a majority of their Tamil opposition had been killed. The conflict lasted 26 years and resulted in over 100,000 deaths, with many more thousands displaced.

Jaffna, Sri Lanka, 1990

© Roger Hutchings/AlamyInterview with Shehan Karunatilaka in the New Statesman

An essay on the origins of the civil war

The New York Times on the civil war

Tea Time with Terrorists: A Motorcycle Journey into the Heart of Sri Lanka’s Civil War – Paperback: 4 Feb. 2016 (non-fiction book)

The Seasons of Trouble: Life Amid the Ruins of Sri Lanka’s Civil War – Paperback: 20 Oct. 2015 (non-fiction book)

Shehan Karunatilaka, Chinaman

Salman Rushdie, Midnight’s Children

Salman Rushdie, The Satanic Verses

Kurt Vonnegut, Slaughterhouse 5

Anuk Arudpragasam, A Passage North

Winner The Booker Prize 2022