A Booker Prize quiz for Burns Night

To mark the annual hootenanny – and the birthday of Scotland’s literary hero – take our quiz that celebrates both Scottish culture and Booker Prize-nominated authors through their words, wit… and whisky

Opinion

How Late It Was, How Late may have divided critics – and judges – but it remains one of the most influential Booker winners and raised prescient questions about decolonisation and self-determination

The culture wars may have flared up in recent years, but the conflict is a long one. Thirty years ago, in the early years of the skirmishes, the announcement of James Kelman’s How Late It Was, How Late, as the winner of the 1994 Booker Prize prompted some particularly sharp exchanges. The issues then were those that remain familiar now – language, nationality, cultural identity – but also, quaint as it now seems, impassioned discussions about the nature of what was then termed ‘literary fiction’.

Kelman’s fault, in the eyes of his critics, was not only to tell the story of an irredeemable working-class Glaswegian down-and-out but to do so both as a stream of consciousness and in language that was raw and, to many, deeply offensive. Kelman’s win ignited what might be called ‘The Battle of the F-word’. According to one critic, Blake Morrison, ‘fuck’ appeared no fewer than 4,000 times in the book, at a regularity of 10 instances per page. To many, this was the very opposite of what the language of a novel should be and provided more than enough evidence to condemn the book.

Kelman fired back in his acceptance speech. Among all the dinner jackets gathered at the Guildhall ceremony, the author arrived in a regular suit and with his tie at half-mast; he was clearly not intending to play the game. In a measured but quietly passionate speech, he said he saw his work as part of a wider move towards ‘decolonisation and self-determination’ and a statement of the ‘validity of indigenous culture’. He stressed too his ‘right to defend in the face of attack’ and sided with the ‘rejection of the cultural values of imperial or colonial authority’. What’s more, his book was part of a fight against ‘cultural assimilation, in particular an imposed assimilation’.

He was not the first Booker Prize winner to take aim at colonial authority: back in 1972, John Berger had caused a furore when he used his acceptance speech to attack the West Indian sugar holdings of the prize’s original sponsor, Booker McConnell. Kelman, though, was not from the Caribbean but from Scotland, and the colonialism he was attacking was cultural rather than economic.

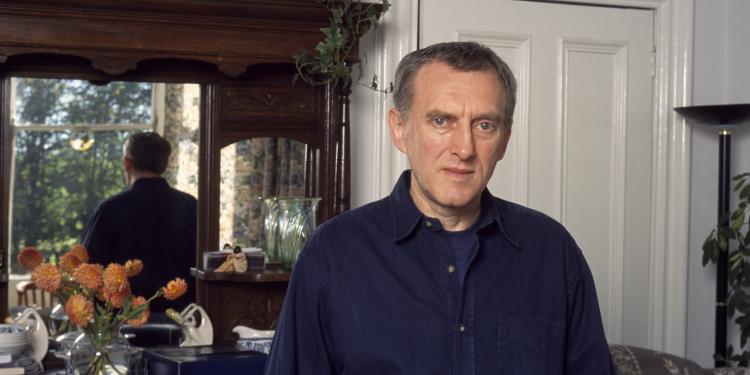

James Kelman

© GL Portrait/AlamyKelman then brought his comments to a rousing finish: ‘My culture and my language have the right to exist,’ he countered, ‘and no one has the authority to dismiss that right.’ He later expanded on this theme, further taking the fight to his critics: ‘A fine line can exist between elitism and racism. On matters concerning language and culture, the distance can sometimes cease to exist altogether.’

With the benefit of three decades hindsight, Kelman has been proved right. His demotic language and unedifying subject matter would prove highly influential. Irvine Welsh, Alan Warner and Douglas Stuart are obvious heirs, with Stuart claiming that How Late It Was changed his life: it was, he said, ‘one of the first times I saw my people, my dialect, on the page’ and Shuggie Bain is indebted to it. Meanwhile, Peter Carey’s True History of the Kelly Gang (2001) utilised a broad and unpunctuated Australian while Marlon James employed an unrepentant Jamaican patois in his A Brief History of Seven Killings (2015). Both followed where Kelman first trod.

How Late It Was itself remains a curious beast. In a 2016 interview Kelman said that he hadn’t set out to shock: ‘It’s not that you make a decision to challenge convention because it’s really irrelevant to you as an artist. All you do is explore, and take it as far as you can. And it’s in the act of doing that that someone will say, “Well, what are you doing here? You can’t use the word fuck.”’ As a young reader he said he avoided English books – ‘Why would you want to read things that were treating you as an animal?’ – so he was clear that what he was writing was not an English book with a Scottish accent. As a Scottish nationalist, he sees England, he has said, as an occupying power. So, he looked ‘within my own culture’ and used ‘the language as people use it’.

Sammy, the central character of the book, is, like Kelman himself, a Glaswegian. Unlike Kelman, he is an ex-convict and a shoplifter, who wakes up from a drink-induced stupor to fall into an altercation with two policemen. They administer a beating so severe that when Sammy regains consciousness, he is blind. What follows is a series of lesser but still harrowing travails, misunderstandings and dead ends. Sammy finds that his girlfriend Helen has left him; his one pair of decent shoes has been stolen; the doctor he consults refuses to believe he really is blind; a benefits officer is equally unhelpful; there is further trouble with the police; he falls out with a friend… The atmosphere is claustrophobic, the settings – streets, pubs, tenements – seedy. The mood is grim.

James Kelman’s speech on winning the Booker Prize 1994

© MGP Photography/Courtesy Oxford Brookes ArchiveIt’s not that you make a decision to challenge convention because it’s really irrelevant to you as an artist. All you do is explore, and take it as far as you can

One of the 1994 prize judges, Rabbi Julia Neuberger, broke ranks to call the book ‘crap’ and ‘deeply inaccessible for a lot of people’ while its win was ‘a disgrace’. The most excoriating attack, however, came from the newspaper editor and commentator Simon Jenkins. For him, How Late It Was was merely a transcription of ‘the rambling thoughts of a blind Glaswegian drunk’, similar to an intoxicated Scotsman Jenkins had once met on a train who concluded their unpleasant encounter by urinating on a train seat. Kelman’s win, thought Jenkins, was an act of ‘literary vandalism’.

Other critics, however, saw beyond the effing and blinding. For Blake Morrison, the book was ‘a novel of exasperation’ whose ‘grim, wearing truth… is that people like Sammy – intelligent but inarticulate, stubborn but self-defeating, prisoners of class prejudice and state repression – don’t stand a chance’. James Wood, another of the judges, acknowledged the book’s ‘atmosphere of gnarling paranoia, imprisoned minimalism, the boredom of survival’ but found that ‘within these limits, and because of them, Kelman is a funny, sour, expansive writer, whose strange, new sentences are brilliant adventures in thought’. He likened Kelman to ‘a musician’ who ‘uses repetition and rhythm to build structures out of short flights and circular meanderings’. Elsewhere, the book was lauded for its ‘enormous artistic and social depth’, its ‘distinctive style’ and its ‘sardonic, abrasive prose’, while A.S. Byatt praised the way the novel is ‘punctuated by a lovely waterfall of four-letter words’.

Kelman’s distrust of ‘standard English’ was partly because it was not of his world: he was brought up in housing scheme accommodation in the more deprived parts of Glasgow and left school at 15. His early reading was self-directed and focused on European existentialist fiction – Albert Camus was a favourite – and American realist writers. Both are present in How Late It Was. In Sammy he portrayed a figure with whom he was familiar, presenting an authentic, unvarnished life narrated in a close mix of the first- and third-person, using the unfiltered language of Glasgow. The book is, among other things, an experiment in late Modernism, not least in being a novel without chapters.

What both critics and detractors agreed on was that How Late It Was is a challenging read. Kelman has suggested that the outrage over his profanities was not entirely genuine – ‘I think, ultimately, it’s something else’ – and his working-class upbringing, his left-wing politics, his Scottishness, his refusal to become clubbable and join the wider British literary culture (he was Booker shortlisted in 1989 for A Disaffection but refused to attend the award dinner saying he had ‘better things to do than swan around with the literati’) might offer alternative reasons. And characters like Sammy too: ‘They don’t want to see these people in literature’, with the word ‘they’ full of import.

Booker Prize judges 1994: Dr Alastair Niven, Alan Taylor, James Wood, Professor John Bayley (chair), Rabbi Julia Neuberger and administrator Martyn Goff

© Caroline Forbes/Courtesy Oxford Brookes ArchiveNevertheless, Kelman has an interest in ‘oratory devices’. So, he finds in the word ‘fuck’ innumerable inflections and meanings – a word of description, of rhythm, of surprise, of imprecation, of exasperation, of class membership, a word that is a sentence-padder and a punctuation mark, and a verbal tic as well as a sexual noun and verb. Above all, perhaps, it is an incantation. ‘Ye’ve got fucking nothing except yer fucking brains’, ‘on his fucking tod’, ‘that’s what he was, a fucking dumpling’, ‘So fuck it, get on with yer life’, ‘Ye’ve got fucking nothing except yer fucking brains’… The word, so inventively used, propels the novel along.

How Late It Was, however, threatened to stall Kelman’s career. Despite winning the Booker Prize and generating the publicity and sales that come with it, the author found himself in a perilous position when the Scottish Arts Council, appalled by his language – and perhaps feeling that it cast wider Scottish culture in an ill light – refused to help finance his next book. Indeed, there was a seven-year gap before the appearance of his next novel, Translated Accounts (2001). Five more have followed, as well as collections of short stories and essays, all interspersed with a spell as a teacher.

Now, partly because of the effect How Late It Was itself brought about, it is rather hard to see why the book generated such a fuss. The vernacular and fruity language no longer merit so much as a raised eyebrow; wrong ’uns and working people have starred in subsequent Booker Prize winners, from Vernon God Little and Milkman to Shuggie Bain; while the novel’s formal qualities now seem so clear as to be barely worth remarking on. Nor is it a book without longueurs and loose ends. Nevertheless, Kelman said that he ‘wanted to write as one of my own people, I wanted to write and remain a member of my own community,’ and that’s what he did. What remains undimmed is the strange dignity he gave to a life like Sammy’s – because he treated it seriously.

How Late It Was, How Late by James Kelman

Winner The Booker Prize 1994