Book recommendations

Reading list

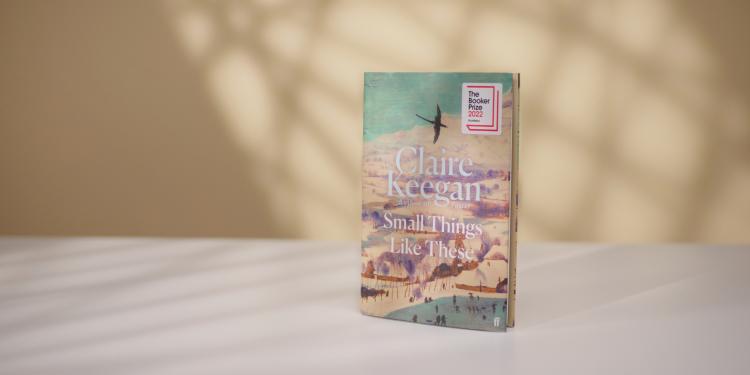

Explore Claire Keegan’s Booker Prize 2022 shortlisted novel Small Things Like These with your book club using our guide and discover why the judges said it ‘explores the silent, self-interested complicity of a whole community’

Download a PDF of the reading guide for your book club

It is 1985, in an Irish town. During the weeks leading up to Christmas, Bill Furlong, a coal and timber merchant, faces his busiest season. As he does the rounds, he feels the past rising up to meet him - and encounters the complicit silences of a small community controlled by the Church.

Claire Keegan’s tender tale of hope and quiet heroism is both a celebration of compassion and a stern rebuke of the sins committed in the name of religion.

Small Things Like These by Claire Keegan

Claire Keegan is a novelist and short story writer, whose work has won numerous awards and been translated into 30 languages.

Keegan was brought up on a farm in Ireland. At the age of 17, she travelled to New Orleans, where she studied English and Political Science at Loyola University. She returned to Ireland in 1992, and her highly acclaimed first volume of short stories - Antarctica - was published in 1999. Her stories are translated into 30 languages and have won numerous accolades.

Claire Keegan

© Frédéric StucinIn a nutshell

Keegan is measured and merciless as she dissects the silent acquiescence of a 1980s Irish town in the Church’s cruel treatment of unmarried mothers - and the cost of one man’s moral courage.

On the characters

It is the tale, simply told, of one ordinary middle-aged man - Bill Furlong - who in December 1985, in a small Irish town, slowly grasps the enormity of the local convent’s heartless treatment of unmarried mothers and their babies (one instance of what will soon be exposed as the scandal of the Magdalene laundries). We accompany Furlong, and we feel - and fear - for him as he realises what is happening, decides how he must in conscience act, and accepts what that action, in a small church-dominated town, will cost him, his wife and his children.

On the book

The book is not so much about the nature of evil as the circumstances that allow it. More than Furlong’s quiet heroism, it explores the silent, self-interested complicity of a whole community, which makes it possible for such cruelty to persist. It forces every reader to ask what they are doing about the injustices that we choose not to think about too closely. Astonishingly, Keegan achieves this without ever sounding angry or preachy.

The Times:

‘The novel isn’t just an eloquent attack on the Magdalene laundries. It is also a touching Christmas tale, genuinely reminiscent of the festive stories of O Henry and Charles Dickens; a novel that has been seeped in sherry and served by the fireside. In one particular moment, when Furlong’s wife and daughters gather to ice the Christmas cake, Keegan’s writing approaches Proust.’

The I:

‘This piercing book - which, at 116 pages, is the shortest novel to ever be in contention for the Booker Prize - examines the way awful suffering can unfold on our doorstep while we carry on with our privileged lives. Through Furlong, it asks: “Why were the things that were closest so often the hardest to see?” And it prompts us to consider what responsibility we have to our neighbours.’

London Review of Books:

‘Keegan does something rare in creating archives of unhappiness, showing the way one sorrow may reverberate with another, how pressure can activate the pain of an old bruise.’

The Washington Post:

‘From the elements of this simple existence in an inconsequential town, Keegan has carved out a profoundly moving and universal story. There’s nothing preachy here, just the strange joy and anxiety of firmly resisting cruelty.’

Independant.ie:

‘It is impossible to change the past but essential to face up to it. That’s precisely what Keegan does in this tender, condensed and pitch-perfect book.’

When his mother’s trouble became known, and her people made it clear that they’d have no more to do with her… (p. 5) Furlong was born to an unmarried mother who died at 16. Due to the generosity of his employer, he was one of few babies born to a person outside of wedlock who got to stay with his mother. Discuss Furlong’s experience and the long-term impact this had on his character.

The Taoiseach had signed an agreement with Thatcher over The North, and the Unionists in Belfast were out marching with drums, protesting over Dublin having any say in their affairs. (p. 13) What was the political atmosphere of the time in Ireland? How did this impact communities such as the one which Bill Furlong lives in?

Lately, he had begun to wonder what mattered, apart from Eileen and the girls. He was touching forty but didn’t feel himself to be getting anywhere or making any kind of headway and could not but sometimes wonder what the days were for. (p. 33) Weariness, worry and repetition are imbued in the story and Furlong’s character seems like a man on the brink. What are the factors that have led to this?

When Furlong first visits the local laundry to deliver some logs, a girl with roughly cut hair begs him to help and take her ‘as far as the river’. Furlong replies by showing his open, empty hands. What does Furlong mean by this gesture? (p. 41)

Inside the laundry, one of the nuns suggests Furlong must be disappointed as he has five girls and ‘no boy to carry on the name’. Furlong replies by saying: ‘What have I against girls?’ […] ‘My own mother was a girl, once. And I dare say the same must be true of you and half of all belonging to us.’ Why is the feminist attitude expressed by Furlong unique for the time and community he lives in? (p. 66 - 67)

After he visits the laundry, a woman who runs the cafe warns Furlong about what he has seen there: ‘Tis no affair of mine, you understand, but you know you’d want to watch over what you’d say about what’s there?’. (p. 94) To what extent did the wider community seem to have knowledge of the real goings-on in the laundries? Do you think the villagers were complicit in the crimes?

The book ends at a point where many other authors would begin their novels’ second act. To what extent is Keegan deliberately asking the reader to create the rest of the story for themselves? What do you think happens to Bill Furlong next?

Those kept in the confines of the laundries were often described as ‘fallen women’. Discuss what is meant by this and how the women in Irish communities were powerless against the church.

Small Things Like These has been described as historical fiction, yet the author disagrees with it being a novel about the Magdalene laundries (Guardian interview, October 21), saying, ‘I think it’s a story about a man who was loved in his youth and can’t resist offering the same type of love to somebody else’. Discuss how Claire Keegan has allowed historical fiction and a deeper character study to intersect.

Economic hardship is woven throughout the narrative of Small Things Like These. How does the author’s use of language and detailing evoke this sense within the novel?

Not one person they met addressed Sarah or asked where he was taking her. Feeling little or no obligation to say very much or to explain, Furlong smoothed things over as best he could and carried on along with the excitement in his heart matched by the fear of what he could not yet see but knew he would encounter. (p. 107) In this scene towards the end of the novel, in which Furlong escorts one of the girls from the laundry outside and through the streets to his home, what personal battle is he also facing?

At 116 pages, Small Things Like These is the shortest book ever to be shortlisted for the Booker Prize. When questioned on this, Keegan previously said, ‘Elegance, to me, is writing just enough’ and went on to say that the character of Furlong ‘isn’t someone who says much’ so a ‘longer novel would not have suited his personality’. Discuss whether Small Things Like These constitutes a novel or novella.

‘It started out as a short story told from the point of view of a boy who accompanies his father to deliver a load of coal and finds another boy, much his own age, locked up in the coal shed at a boarding school. His father just locked the door then went on to make the next delivery, saying nothing.

‘At some point, the coalman’s point of view took over and I became preoccupied with him and it felt

necessary to explore how he, the father, would carry this knowledge around with him on his rounds, through his days, through his life and how or if he could or would still regard himself as a good father. I’m not even sure if this man, Furlong, can regard himself as a good father after this novel ends - as he may have deprived his daughters of a decent education and may lose his business, may not be able to provide for his family.

‘I’m interested in how we cope, how we carry what’s locked up in our hearts. I wasn’t deliberately setting out to write about misogyny or Catholic Ireland or economic hardship or fatherhood or anything universal, but I did want to answer back to the question of why so many people said and did little or nothing knowing that girls and women were incarcerated and forced to labour in these institutions. It caused so much pain and heartbreak for so many. Surely this wasn’t necessary or natural?’

Read more of Claire Keegan’s interview on the Booker Prize website.

Claire Keegan

© Ulf Andersen/GettyFrom 1922 until 1996, thousands of girls and women were held prisoner in ‘Magdalene laundries’ in Ireland. These workhouses were commercial and profit-based laundries run and funded by the Catholic Church and the state.

The true figure of those held remains unknown but it is often said to be at least 10,000, though some have guessed the real figure may be as high as 30,000. Records from the laundries were deliberately destroyed, lost or made inaccessible by the church. While there, the women were forced to labour tirelessly, while suffering physical and mental abuse at the hands of the church.

The women and girls who were unwillingly held were often described as ‘fallen women’. They tended to be unmarried mothers and their daughters, those who had grown up in church or state care, women with mental health issues or disabilities and those who had suffered sexual abuse.

Confined for decades while starved of food and education, many became isolated from society and institutionalised. While there, many lost their own lives, as did their children.

In the early 90s, 155 unmarked graves were discovered on the land of a convent in Dublin which eventually triggered a public scandal and a wider awareness of the laundries. In 1994, folk singer Joni Mitchell wrote a song titled The Magdelene Laundries, which was included on her album Turbulent Indigo. In 2002, The Magdelene Sisters was released in cinemas depicting four women incarcerated in a Dublin laundry. 2013 saw the release of the tragicomedy film Philomena, about a woman desperately trying to find her forcefully adopted son, after life in a laundry. Stories of laundries persist in media and the arts, with many more books, plays and screen adaptions of the women’s stories. Despite this, the last Magdalene laundry only stopped operating on 25 October, 1996. No apology was issued by the Irish government until 2013.

Campaigners and survivors of Catholic-run institutions outside Sean McDermott Street Magdalene Laundry, Dublin, 2017

© PA Images/AlamyHistory.com overview of the Magdelene laundries

Claire Keegan interview in the Guardian

Ireland and the Magdalene Laundries: A Campaign for Justice by Katherine O’Donnell. A non-fiction documentation of the ongoing work carried out by the Justice for Magdalenes group in advancing public knowledge and research into Magdalene laundries.

Do Penance or Perish by Frances Finnegan. A non-fiction account tracing the development of Ireland’s Magdalen Asylum.

Watch: The Magdalene Sisters, Peter Mullan’s 2002 drama about the Magdalene laundries, starring Anne-Marie Duff and Geraldine McEwan.

Claire Keegan, Foster

Claire Keegan, Antarctica

The Selected Stories of Anton Chekhov

William Trevor, Reading Turgenev

Katherine Mansfield, The Garden Party and Other Stories

George Saunders, A Swim in a Pond in the Rain