Claire Keegan interview: 'A longer novel would not have suited my main character's personality'

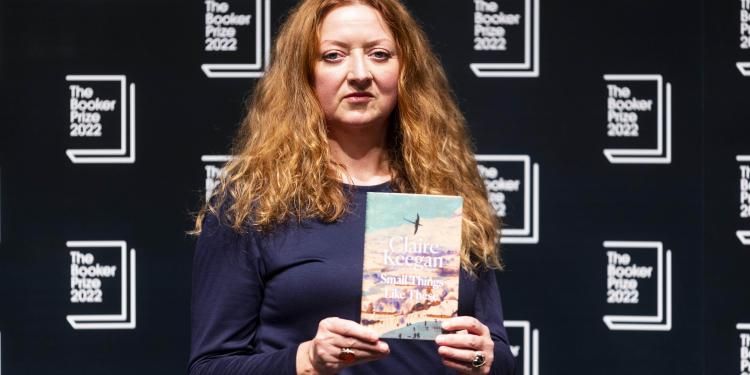

With Small Things Like These shortlisted for the Booker Prize 2022, Claire Keegan talks about the importance of restraint, why she’s more interested in tension than drama… and why not writing is more difficult than writing

How does it feel to be longlisted for the Booker Prize 2022 and what would winning the Booker mean to you?

It’s both a privilege and an honour to see this novel nominated for the Booker Prize, to know that the judges consider it worthy. I’ve no idea what winning would mean, don’t know that anyone could know what winning would mean unless or until it happened - and even then, its meaning might be difficult to articulate. More readers is the most obvious answer - readers who might not otherwise find your work finding your work.

There was an 11-year gap between your last book, Foster, and Small Things Like These. How long did it take to write Small Things, and what does your writing process look like? Do you type or write in longhand? Are there multiple drafts, sudden bursts of activity, long pauses? Is there a significant amount of research and plotting before you begin writing?

I don’t like to think about how long it took to write this book. The story was rumbling in the back of my mind for a long time, some years, before I ever began and then I went through a period of taking notes and trying not to write it. I’m always reluctant to go in - and my early drafts are the most difficult to compose and face. At the beginning, little or nothing works on a level of suggestion. It seems to me that all good stories are told with varying degrees of reluctance - and in my case the author, too, is reluctant to go in. But not writing is almost always more difficult than writing.

There must be 50 or so drafts. I’ve kept them all and they filled two large boxes. I take notes in longhand then make the incision in time and choose a point of view, and begin freshly, on the screen. Long pauses don’t work for me. There is no magic drawer in my house that makes the work look better after it is put away for months, but I understand that other writers do find this useful.

I don’t ever plot. And I do very little research, as little as possible. I prefer to use my imagination. Language is older and richer than we are and when you go in there and let go and listen, it’s possible to discover something way beyond and richer than your conscious self. It seems to me that when we fail, it’s because our imagination fails us. I believe this to be true of both life and literature.

Where do you write? What does your working space look like?

I write at home. This book was written in my sitting room overlooking the Wexford coast, and was completed during lockdown. I wrote for several hours every night and morning during those 18 months, as my fellowship at Trinity College was cut short when the pandemic began and I didn’t have the usual commitments to my students.

If it was at all cold, I kept the fire going. It’s nice to have a fire in the room you’re working in. Long, dark mornings can also be a great help. And a young ginger cat came straight up to me out of the bushes and moved in and slept on an old sheepskin on my desk, as though that’s where he wanted me to be. In the finish, for that final year and more, I was probably averaging eight hours a day at the desk, something I’d never done.

Small Things Like These is the shortest book to have been longlisted for the Booker in its entire history. Did you know from the outset that it was going to be a short book? Are your earlier drafts much longer?

It isn’t possible at the outset to know what length a book will be. I’ve never set out to write something short except when there was a set word limit for a short story competition or a commissioned piece. But I’ve always been interested in choosing well and putting what’s chosen to good use, reusing those choices made. I’m more interested in going in than going on.

There’s a wonderful letter Chekhov wrote to his brother Alexander about the meaning of grace, how grace is when you make the least number of movements between two points - and that type of athletic prose has always appealed to me, coupled with light-handedness and restraint. Elegance, to me, is writing just enough. And, as James Baldwin said, in his Paris Review interview, ‘the hardest thing in the world is simplicity’.

I’m interested in transitions, paragraph structure, in what happens between paragraphs, those leaps in time. And Furlong, my central character, isn’t someone who says much. He’s a most unwilling narrator, so I was obliged to stay within his mindset, his reluctances. A longer novel would not have suited his personality and it’s all told from his point of view, so it was my task to oblige him in this way, to be well-mannered towards and abide by his reserve.

Small Things Like These by Claire Keegan

Where did the idea for the book come from? What was your starting point? Was it a character or situation, or broader events in Ireland or elsewhere?

It started out as a short story told from the point of view of a boy who accompanies his father to deliver a load of coal and finds another boy, much his own age, locked up in the coal shed at a boarding school. His father just locked the door then went on to make the next delivery, saying nothing.

At some point, the coalman’s point of view took over and I became preoccupied with him and it felt necessary to explore how he, the father, would carry this knowledge around with him on his rounds, through his days, through his life and how or if he could or would still regard himself as a good father. I’m not even sure if this man, Furlong, can regard himself as a good father after this novel ends - as he may have deprived his daughters of a decent education and may lose his business, may not be able to provide for his family.

I’m interested in how we cope, how we carry what’s locked up in our hearts. I wasn’t deliberately setting out to write about misogyny or Catholic Ireland or economic hardship or fatherhood or anything universal, but I did want to answer back to the question of why so many people said and did little or nothing knowing that girls and women were incarcerated and forced to labour in these institutions. It caused so much pain and heartbreak for so many. Surely this wasn’t necessary or natural?

When this book won the Kerry Prize for best Irish novel, one of the judges said the book left her with the question: so what are you going to do now with what you believe in? This response alone made the book worth writing.

Although the book features one of Ireland’s Magdalene Laundries, you have said elsewhere that it is not about the Laundries. What would you say the book is about? Love, kindness, duty - something else?

It’s the story of a coalman named Bill Furlong who lives with his wife and five daughters in a small town, set in the weeks coming up to Christmas…

I can’t now help thinking of Flannery O’ Connor, who said that a story is a way to say something that can’t be said any other way, and it takes every word in the story to say what the meaning is!

I know some readers see it as a story of a simply heroic character. I’m not saying that my character isn’t heroic - but I see Furlong as a self-destructive man and that this is the account of his breaking down. He’s coming into middle age, suffering an identity crisis, doesn’t know who his father is, and he’s also coming to terms with the fact that he was bullied at school. And his workaholism, which until now has kept the past at bay, is wearing thin. It’s also a portrait of how difficult it was to practise being a good Christian in Catholic Ireland.

But I also like to think it’s a book about love. Furlong was loved as a child, was wanted at a time when so many children born within and outside of wedlock were unwanted. It was the English poet, Philip Larkin, who wrote that beautiful line ‘what will survive of us is love’ - and I like to think that this book has something to answer back about this, and for better or worse perhaps prove it true. Without being loved as a child, Furlong might have been brutalised, grown hard as others did and self-centred - and might also have done nothing.

Like another Irish book on the 2022 longlist, Audrey Magee’s The Colony, an uncomfortable period in Ireland’s history casts a shadow over the main narrative. Is Ireland’s past unavoidable for Irish writers?

I don’t believe Ireland’s past is any more or less unavoidable or avoidable than any other country’s past is for writers of other nationalities.

The book is set in 1985 yet in many ways feels timeless. What was the significance of setting it in the mid-Eighties?

Well, it could not have been set after the Ferns Report was published, as the Catholic Church had by that time lost much of its power and was collapsing. I didn’t want to set it in a time before motor vehicles because that would suggest it was something of the distant past, not a society of my own generation’s making. If it was set in another time, it might not have allowed me to question and criticise the society we ourselves created, our current misogynies and fear, the cowardices and silences and perversities and survival tactics of my own generation.

Claire Keegan

© Ulf Andersen/GettyIf it was set in another time, it might not have allowed me to question and criticise the society we ourselves created, our current misogynies and fear, the cowardices and silences and perversities and survival tactics of my own generation.

Which book or books are you reading at the moment?

I’m reading the Norton Anthology of Short Stories, edited by Richard Bausch. as I’ll be running a course on the short story in February and want to prepare and teach new stories. I’ve just read The Management of Grief by Bharati Mukherjee and the essay Richard Ford wrote on the story, both of which will be included on the syllabus. They’re wonderful.

Do you have a favourite Booker-winning or Booker-shortlisted novel and, if so, why?

The Remains of the Day is the first that comes to mind. I’ve this belief that good writing is good manners - and Ishiguro’s novel is such a beautiful example of elegance and tact. Quiet, restrained prose is what attracts me. I’m more interested in tension than in drama.

It’s impossible to not also think of McGahern’s Amongst Women, a well-loved novel here in Ireland, which was shortlisted. And Roddy Doyle’s The Van. I was sitting in a hospital waiting room when reading the end of that novel. The ending fell so beautifully into place and I felt he stopped when he could have gone on, and didn’t. Again, I suppose it’s the restraint that I admire, or one of the many things I admire, in his prose.

Last year’s winner, The Promise, by Damon Galgut, is such a fine novel - but for a long time I’ve admired Galgut’s work, which I have taught. I was so pleased that his novel won last year.

What’s the one book you wish you’d have written?

There isn’t any book I wish I’d written for the simple reason that it wouldn’t be mine. It would feel like theft. Or it could mean I’d have to be dead. I don’t covet anyone else’s work, need to write my own, need to earn my prose. If I were pressed, I’d probably choose The Great Gatsby.

What are you working on next?

I’m settling down to work on a book set on the farm where I grew up in Wicklow. It is a mother’s story. The parts have not yet cohered in my mind as I’m still at the note-taking stage - but September is round the corner, and it’s time to settle down to the desk for the autumn and light the fire and see which way the wind blows. It may, of course, turn out to be something else entirely.

We are so thrilled that Audrey Magee’s The Colony and Small Things Like These by @CKeeganFiction are on the #BookerPrize2022 longlist.

— Faber Books (@FaberBooks) July 26, 2022

Here is what the judges had to say about these two incredible novels: pic.twitter.com/r4mEcslXPE

Discover more about the author

- By

- Claire Keegan

- Published by

- Faber