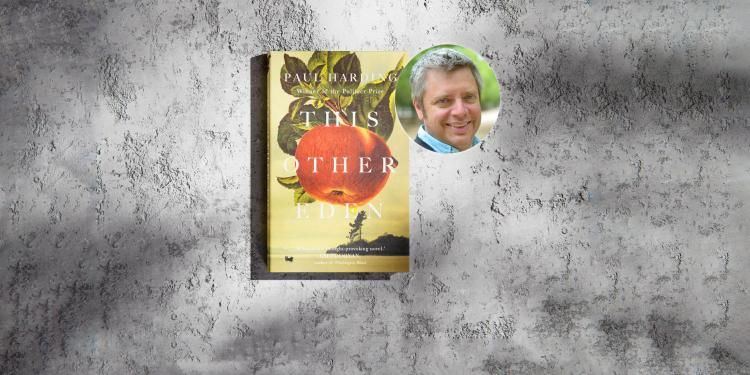

An extract from This Other Eden by Paul Harding

Full of lyricism and power, Paul Harding’s spellbinding novel celebrates the hopes, dreams and resilience of those deemed not to fit in a world brutally intolerant of difference

With This Other Eden shortlisted for the Booker Prize 2023, we spoke to Paul Harding about the real island that inspired the book, and why his method of writing is like musical improvisation

Read interviews with all of the shortlisted and longlisted authors here.

How does it feel to be nominated for the Booker Prize, and what would winning the prize mean to you – especially as someone who has already received one of the world’s biggest literary awards?

I feel joy, humility, and gratitude in equal measure at being nominated. Winning the prize would be miraculous. I will always perceive awards like the Booker the way I did when I was a bookseller. Reading the prize-winning books, beginning in the late 80s, was like being given a treasure every year: Ishiguro, Byatt, Okri, Ondaatje, Swift, Roy, and on and on. The idea of being associated with those great writers, through such a prize, is still pretty much unimaginably wonderful to me, even though my first novel had the great fortune of receiving an award.

How long did it take to write This Other Eden, and what does your writing process look like? Do you type or write in longhand? Are there multiple drafts or sudden bursts of activity? Is there a significant amount of research and plotting before you begin writing?

I absolutely love writing without having any idea of what comes next. I love having no plan beyond an initial image or tone or sense of atmosphere and just letting everything that comes over the wire into the manuscript, at least for the first couple years or so. I love observing the phenomenon of what physicists call ‘emergence’, where the form of the book, plot, characters takes shape through a process I guess I’d liken to musical improvisation. I love the sense of being the story’s amanuensis.

Months will go by during which, to all appearances, I’m napping on the couch. Really, I’m writing – riding the updrafts as I like to think of it, letting what I’ve written and what I’ve read and looked at and listened to percolate and simmer together. Then, there will be a sudden burst of activity, like you say.

I type, write in longhand, whatever means is convenient whenever a sentence or phrase or word occurs to me. This Other Eden was without exaggeration mostly written on Post-it notes. They’d sort of end up shingling the living room and study and office and I’d periodically scrape them up and tape or staple or transcribe them into notebooks and eventually type them into the big manuscript document. I’m like a magpie; I pick up whatever shiny or colourful bit of language that catches my attention and throw it into the kettle. I love seeing how elements that seem disparate implicate themselves with one another over the years.

Paul Harding

I think eugenics was a perfect example of how every idiom and discipline of human thought is equally vulnerable to perversion and degradation, which is to say, utterly

Where exactly do you write? What does your working space look like?

When I first became a parent, about 23 years ago, and had a newborn to take care of with my wife and taught full time during the days and part time nights, every trace of needing a particular place or time or ritual in order to invoke the muses was quickly burned away. I learned how to pretty much open a notebook or laptop wherever I stood or sat and work on the single sentence or two at hand for whatever time I had. At first it was a horror, but now I love it because it feels totally coextensive with everything else I do, rather than separate. It feels rewardingly work-person-like, in the way Herman Melville somewhere describes the writing of Moby Dick as ‘ditcher’s work’.

This Other Eden is inspired by the true story of Malaga Island, a tiny piece of land off Maine which forcibly removed its residents. What was it about this story that particular captivated you, and when did you come across it? Did you visit Malaga Island as part of your research?

I was reading about labor unions in the US after the American Civil War, which were some of the first institutions in the country to advocate for things like civil rights and women’s suffrage and so forth, and it occurred to me that there must have been all-Black and racially integrated communities at the time. I did a quick search online and, of course, there were so many of them, all around the country. Malaga Island caught my eye at first because it was in the state of Maine, where my mother’s family was from and where my first novel, Tinkers, is set. When the people there were evicted, one family was committed to the Maine School for the Feeble Minded, which served as the source for an asylum that plays a part in the plot of Tinkers. Then I discovered that almost to the week that the community was dismantled, in the summer of 1912, the first international congress was taking place in London. Those three elements and the photographs of the residents that I saw in the three or four articles I found about the story sort of spontaneously constellated in my imagination and began to haunt me.

The moment I was compelled to write fiction about that kind of situation, I stopped reading about the factual history of Malaga. I have no personal connection with that community or the actual families that went through that catastrophe. Their story – factual, historical – is not mine to write. So, I immediately set about getting an imagined version of the events and, more importantly, the characters up and running, in which I’d be free to shape the story in the context of different literary traditions that resonated with what seem like the universal human experiences of displacement, marginalization, exile, and so forth. I’ve not been to Malaga Island.

This Other Eden by Paul Harding

To what extent are the characters in the book fictitious or based on real individuals? Did you always intend to stretch the boundaries of more traditional historical fiction, and where did you decide to draw the line between fact and fiction? Were you inspired by other historical novelists?

There’s a kind of continuum of ‘historical fiction’, ranging from, say, basically documentary narrative to mostly imagined fiction that germinated from some historical setting. The line I tried as best I could to draw between fact and fiction was the maybe couple dozen factual details that most struck me in the limited reading I did about Malaga and what they subsequently led to when I imagined my way beyond them. From the moment the historical events began to suggest connections with stories like Noah’s Ark, the Garden of Eden, The Tempest, Sarah Orne Jewett’s Country of the Pointed Firs, Moby Dick, Harriet Jacob’s memoir, and so forth, I moved toward the purely fictional because I wanted a kind of poetic license to intermingle the material with those influences – to experiment with the intermingling – in a way that would not be appropriate if I were using real names, real people.

The story is deeply concerned with eugenics, which operated under the guise of ‘science’ during the Malaga Island evictions. How do you think the issue of eugenics in the novel reflects contemporary societal issues and debates? To what extent is This Other Eden intended to be a cautionary tale with parallels in today’s world?

I think eugenics was a perfect example of how every idiom and discipline of human thought is equally vulnerable to perversion and degradation, which is to say, utterly. And I suppose it’s also to say always, too. It doesn’t take too much looking around the world today to find our own bigotries and misadventures papered over with the would-be imprimaturs of science, religion, or whatever is perceived to carry the weight of authority at the moment. As idioms of human thought and exploration into the nature of the cosmos and the nature of humans themselves, science and religion, for example, are both high watermarks of the human mind. What people do with and to and in the name of them is where the cautionary tales lie, I think.

This Other Eden contains religious undertones and more explicit biblical references, from the novel’s title to the rapturous beginning (with nods to the story of Noah’s Ark), to the Christian beliefs of the islanders. What role did you intend religion and faith to serve in the novel?

I didn’t think of religion as having a role so much as being one of the idioms – of thought, story, narrative, etc. – through which I wanted to refract aspects of the story and the character’s experiences. I teach the Old Testament and a lot of Shakespeare, whose plays make practically constant use of the Bible and its stories. And when I read Melville or Morrison or Faulkner I can hear Shakespeare and the Bible in their works. And I have this deep pleasure and satisfaction of trying to write in ways that people reading my books will hear all of them in my work. I take great aesthetic delight in daydreaming about a tradition from Moses – or, even, Babylon and Egypt, since Moses was deeply influenced by those traditions – to the present, and of hitching my own work to that tradition, not in any presumptuous way, but aspirationally (if that’s a word), like from the privilege and joy of influence, rather than any anxiety.

Which book or books are you enjoying at the moment? In particular, could you direct us towards an underrated contemporary writer who deserves more attention and accolades?

I don’t think Edward P. Jones is recognised enough for being the singular writer he is. There are tons of others I can think of, but then I don’t want to name a bunch and think of all the others I neglected to mention later and feel bad about leaving them out!

Do you have a favourite Booker-winning or Booker-shortlisted novel and, if so, why?

There’s not one favourite, but because he was a dear personal friend and wonderful teacher, and because I found his Booker co-winning novel Sacred Hunger so overwhelming when I first read it in 1992, Barry Unsworth holds a permanent place in my heart. But now I’m already feeling bad, because there’s Desai and Saunders and James….

What are you working on next?

As with each of the three novels I’ve published so far, I haven’t had the slightest idea for another novel for the past year and probably won’t for the next one or two years, if the past is any indication. I barely seem to be able to squeak out a book every ten years, I think and write so slowly!

Paul Harding