Long read

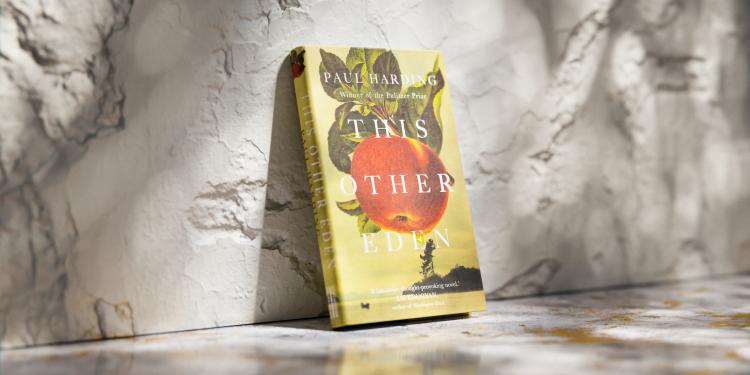

Full of lyricism and power, Paul Harding’s spellbinding novel celebrates the hopes, dreams and resilience of those deemed not to fit in a world brutally intolerant of difference

Inspired by historical events, This Other Eden tells the story of Apple Island: an enclave off the coast of the United States where castaways - in flight from society and its judgment - have landed and built a home.

In 1792, formerly enslaved Benjamin Honey arrives on the island with his Irish wife, Patience, to make a life together there. More than a century later, the Honeys’ descendants remain, alongside an eccentric, diverse band of neighbours.

Then comes the intrusion of ‘civilization’: officials determine to ‘cleanse’ the island. A missionary schoolteacher selects one light-skinned boy to save. The rest will succumb to the authorities’ institutions - or cast themselves on the waters in a new Noah’s Ark…

A hurricane struck in September of 1815, twenty- two years after Benjamin and Patience Honey had come to the island and begun the settlement, by which time there were nearly thirty people living there, in five or six houses, including the first Proverbs and Lark folks, the ones from Angola and Cape Verde, the others from Edinburgh — Patience herself from Galway, Ireland, originally, before she met Benjamin on his way through Nova Scotia and went with him — and three Penobscot women, sisters who’d lost their parents when they were little girls. A surge of seawater twenty feet high funneled up the bay, sweeping houses and ships along with it. When the wall of ocean hit, it tore half the trees and all the houses off the island, guzzling everything down, along with two Honeys, three Proverbs, one of the Penobscot sisters, three dogs, six cats, and a goat named Enoch. The hurricane roared so loudly Patience Honey thought she’d gone deaf at first, that is, until she heard the tidal mountain avalanching toward them, bristling with houses and ships and trees and people and cows and horses churning inside it, screaming and bursting and lowing and neighing and shattering and heading right for the island. Then she knew all might well be lost, that this might well be the judgment of exaltation, the sealed message unsealing, that after they’d all been swept away by the broom of extermination there’d be so few trees left standing a young child would be able to count them up, and their folks would be scarcer than gold. But not all gone. Not everyone. Patience knew. Some Honeys would persist, some Proverbs survive. A Lark or two might endure. So, for reasons she could never afterward explain, she snatched the homemade flag she’d stitched together from patches of the stars and stripes and the Portuguese crown and golden Irish harp shaped like a woman, who looked so much like a figurehead and always reminded her husband of the one on the front of the ship he’d been a sailor on, that had sunk off the coast and brought him to the island in the fi rst place, and the faded, faint squares embroidered with Bantu triangles and diamonds and circles that he’d carried with him everywhere, that he showed her meant man and woman and marriage and the rising sun and the setting sun, that he always said were his great-grandfather’s, although she in her heart of hearts didn’t think that that could be true, and tied it like a scarf around her throat, and she took Benjamin by the hand and dragged him from their shack out into the whirlwind. She swore it was a premonition, because no sooner had she and her husband passed out the door than the house broke loose from its pilings and tumbled away behind them, bouncing and breaking apart into straw like a bale of hay bouncing off a rick and into the ocean. Now that she stood in the open, facing the bedlam, her legs would not work. She was sure that this was the Judgment and what was to be was to be; it was useless to try to outrun the outstretched arm of the Lord.

Benjamin roared to her over the roaring storm, The tree, the tree! And he pointed to the tallest tree on the island, the Penobscot pine, at the top of the bluff . Benjamin pointed and leaned his face toward his wife’s and pointed.

Up the tree!

Paul Harding

The water hit the south shore of the island first and swallowed it whole and smooth. Then it hit the jagged bedrock spine running up the middle of the island and broke over it hissing like a saw blade

Wind plastered his shirt and the rain lashed and streamed down his face and ran from his hair and lightning broke across the sky and thunder blasted against the earth and sea and he roared again over the roaring storm, The tree! And Patience thought of their grown children and their young grandchildren and cried to her husband, The children! And Benjamin looked beyond his wife and there were their children and grandchildren, drenched and shouldering their way against the winds and lashing rains, the ocean rising now up to the windows of the Larks’ old shack and pouring into it through the broken panes, and the largest surging waves thundering nearly up to where his own house had stood not two minutes before and sucking all the earth right off the very rocks and into the black and gray and brooding jade Atlantic, and he cried, Go to the tree! And he ran toward his grown children and young grandchildren and grabbed two soaking little ones from their mothers and carried one each under his arms and ran toward the tree. And the wind roared and spun and they staggered against it, now nearly blown toward the bluff , now nearly blown back away from it. When they reached the tree, one of Benjamin and Patience’s sons, I think she always said it was Thomas, stood on Benjamin’s shoulders and the other sons and daughters climbed up the two men and reached the lowest branches of the old tree and once they got their footing as best as they could in the middle of bedlam, the others tossed the waterlogged children up to them one by one. Once Patience had climbed into the tree, and Thomas followed her up from Benjamin’s shoulders, Benjamin himself scaled the trunk like the mast of a ship and roared once more: As high as ye can climb! And all the Honeys in that old tree climbed with all their strength, the children screaming and crying, the men and women screaming and crying, until the whole soaked clan clung together and to the trunk in a trembling, grasping cluster at the top of that swaying, bending, mighty old tree snapping back and forth in the wind like a whip. And right then they all heard a greater thunder rumble from the clamor and the whole island quaked under them, telegraphing their extinction. And at that moment, Patience Honey, holding one of her grandbabies tight as could be against her side with one arm, and clenching the tree with the other, looked to the south, down the bay, and there she saw that piled ocean, all the trees and buildings and shrieking people and wagons and sloops and schooners churning in its saltwater guts, and an old sea captain named Burnham in his pilot coat rowing a dinghy on the blazing crest of it all, smoking a pipe, bowl- downward to keep the water out, crying for mad joy at this last rapturous pileup, and all of it, that great massif of water and ruin speeding right for the Honeys in their tree, which now seemed like a twig, a toothpick, a drenched blade of grass set against the immensity of that mountain range of ocean and demolition. What was always so eerie about it afterward, Patience always said, what was so terrifying about it that made her bowels feel as if they’d turned to sand, was how quiet it all seemed, like a breath drawn and held, right before it hit, how breathtakingly fast but nearly silent and so just plain beautiful it was, all those people and trees and ships and horses cartwheeling past within the billows. It wasn’t silent, really, but more, so loud it was too big to hear. I could not hear it for that second, because it was just too big a sound for my ears to hear.

The water hit the south shore of the island first and swallowed it whole and smooth. Then it hit the jagged bedrock spine running up the middle of the island and broke over it hissing like a saw blade. When it struck the slope of the bluff it exploded across the horizon in front of the islanders in the tree, hung up and suspended for a moment in an apocalyptic entablature, that Patience afterward always said looked in that instant before it all collapsed back together and swept along how the parted sea must have appeared to the poor Israelites. I was pretty well given up on it all and in that tree holding it so hard the bark cut into my arms and gave me these scars and holding that baby so hard against me I thought I’d crack it, drenched to the marrow and screaming and trying not to let go, but when that tower of ocean and ruination burst apart in front of me, in a blink, but deep as my soul, I saw a broad, dry avenue running through the middle of the sea, and it was thronged with shepherds and sheep and old ladies on donkeys, litters of children curled up asleep on hay in the beds of rickety carts. The parted ocean towered on both sides, sheer, smooth, and monolithic. And inside the water, a pell-mell cavalcade of Egyptian men and horses and chariots scrolled past, tumbling heel over headdress, fetlock over cannon, bumper over shaft. Most of the men wore linen tunics, but some wore leopard skins and feathers and had elaborate headdresses. Some of them were tethered to their chariots by leather reins and held longbows. Arrows and spears twirled among the men and horses and cars. Their black- lined eyes stared wide open, but they were all clearly drowned. And I knew what it was like when God parted the sea. And I knew that Moses was way up there at the front of the line. Not like the idea of Moses, but the man himself. The very man, Moses. When God opened the ocean. Then the waters collected all the relic and rubble back up and swept over the rest of the island. The water churned and rose and rose up the Penobscot pine laden with the Honeys.

Patience looked down through the branches and limbs and watched the seething waters rise over her children’s and grandchildren’s feet, billow up their skirts and rise over their midriff s and up their exposed throats then into their sputtering mouths, and she watched their hair soak up the boiling waters, and she watched the waters swill Benjamin up, too, and she watched her daughter, Charity Honey, wrench free from the tree and tumble away in the wreckage clutching her baby son, David, in her arms, and the waters reached her feet and she felt something deep down in the bottom of the tree crack and give and the tree bowed and she was in the swift and roaring waters up to her waist. Then the tree levered itself back upright. Though it seemed not to swallow at her quite as greedily as it first had, the water still rose, and it reached Patience’s collarbone and Patience always said she could still just see the top of Benjamin’s head below her in the water, serene, almost, almost becalmed, tiny bubbles of air rising from his hair. And it was then, just as the water touched it at her throat, that Patience remembered the old flag she’d sewn for Benjamin from the bits and pieces of other flags and national rags and bedraggled patches, not long after they’d married and first settled their now drowning island, still tied around her neck. She always said later, I just decided right then that if we were all going to Judgment, I was going to fly our little flag until the last possible second. So, I hoisted that baby up even more and pressed it between the tree and my breast harder than I ever otherwise would have dared and freed my hand and somehow unknotted the flag from my neck and held it in my hand and held my hand up just as high as I could get it, and the wind took the flag up and snapped it and practically tore it from of my grasp but I kept hold and there it flew. Then the water rose over the baby, who’d gone past wailing and just stared, wedged between my body and the tree, dumbfounded at the pandemonium, wide- eyed and quiet as it burbled under, and the water reached my mouth and covered my face and went over my head, and still I held that foolish flag as high as I could, and the water rose up my shoulder, and the water rose up to my raised elbow, and the water rose up my forearm, and the water reached my wrist, and so there was just my one hand holding that motley little tattered flag sticking up above the surface of the flood, and the waters rose up my fingers, and just as my hand was about to disappear and that flag and all us Honeys be swallowed up in the catastrophe, the water stopped rising.

The surge struck the innermost of the bay, spilled onto the mainland, dumping the foremost of the ruin it had plowed along the way onto a campsite called Little Shell Cove, where a hundred years later campers still turned up trinkets from the calamity, and the cauldron of wrath doubled back on itself and withdrew, quaffing the people, creatures, pie safes, pews, and catboats it had failed to devour the first time caterwauling off toward the horizon.

The water stopped rising and seemed to pause. It was as if my hand and the sputtering flag were at the center of a great whirlpool guzzling the island down its throat but then the eddying slowed and stopped then began to unwind.

This Other Eden by Paul Harding