The Booker Prize Podcast, Episode 1: The best Booker books ever (maybe)

In the first episode of The Booker Prize Podcast, our hosts – author and critic Jo Hamya and broadcaster and critic James Walton – get to know each other by discussing their favourite books from the Booker Library

Listen to more episodes from The Booker Prize Podcast here.

The Booker Prize Podcast – our brand-new weekly podcast – has officially launched. You can now join us each Thursday as we dust off shortlists from years gone by, revisit past ceremonies and even explore some of the prize’s most controversial moments. We’ll also be as sharing exclusive, behind-the-scenes content from this year’s International Booker Prize and Booker Prize.

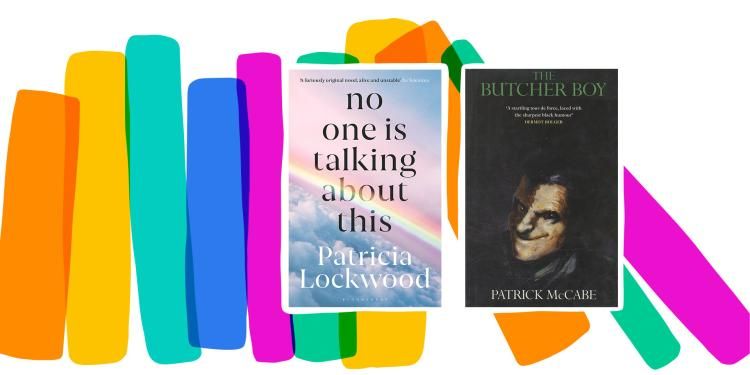

In this pilot episode, our hosts – novelist and critic Jo Hamya and critic and broadcaster James Walton – break the ice by discussing their all-time favourite novels from the Booker archives: Patrick McCabe’s The Butcher Boy and Patricia Lockwood’s No One Is Talking About This.

Together, they explore the themes and cultural impact of their chosen titles, while sharing personal insights and perspectives, revealing exactly why they think the books claimed their spot on the shortlists.

This episode contains significant plot details.

Patrick McCabe and Patricia Lockwood

In Episode 1, Jo and James talk about:

- Why Patricia Lockwood’s No One is Talking About This, a two-part novel that captures our deep entanglement with the internet through its blend of laugh-out-loud humour and beautifully-observed prose, might have won the 2021 Booker Prize.

- Why Patrick McCabe’s The Butcher Boy, a 1992 Booker-shortlisted novel that follows a young man’s descent into madness in small-town Ireland, isn’t a virtuous read – but it is one that will blow your socks off.

Jo Hamya and James Walton

© Hugo GlendinningBooks discussed in this episode

No One is Talking About This by Patricia Lockwood

The Butcher Boy by Patrick McCabe

Priestdaddy by Patricia Lockwood

Fake Accounts by Lauren Oyler

Episode transcript

/* /*]]>*/ James Walton: Hello, and welcome to a new podcast, something I think we can all agree that the world badly needs. This one is the Booker Prize Podcast, which, as the name unambiguously suggests, is brought to you by the Booker Prizes, the UK’s most famous literary award - although, I promise, not in a propaganda-ry or over-reverent sort of way.

Jo Hamya: So, we are on the Strand. There are bells tolling behind us and I can see people going about their daily business while we sit up here recording a podcast, you know-

JW: Little knowing that podcast magic is about to be made.

JH: Exactly. They don’t know what’s coming to them! And I’m sitting across from James. I had no idea who my co-host was going to be. And it was so funny when I first walked into the room that we met in to talk about the idea for this show. And I saw that - I don’t think you’ll disagree with me, James - you are my polar opposite in every single way imaginable.

JW: Hold on a minute. Well, well, I… I sort of know what you mean! It was like a sort of slightly weird blind date, wasn’t it?

JH: Yeah, it really was. But then I thought, you know what? We are going to get something amazing out of this. And James, yes, I’ve only just met you, but as far as I’m aware you’re a brilliant writer and you are also a sometime radio host and a-

JW: Seventeen series, if you don’t mind, of a top literary quiz on Radio 4. No, it’s absolutely fine. When you say polar opposites, you mean by the sort of main-

JH: The obvious things, you know?

JW: By the main markers?

JH: Yeah, exactly.

JW: Of today, aren’t they?

JH: Yeah, exactly.

JW: Gender. Race. Age.

JH: Age.

JW: But… they’re not the only things in the world.

JH: They’re not! And the first thing we bonded over was the fact that we believe that people should still be able to smoke indoors.

JW: Oh yes, that’s right. Yes. So, no, that’s right. Smoking does work, doesn’t it? We popped out for a fag and that was basically all sorted.

JH: And today we’re going to be discussing our favourite Booker novel, across time.

JW: So, Jo, what have you gone for here?

JH: I’ve gone for Patricia Lockwood’s No One is Talking About This, which was shortlisted in 2021. I was a Patricia Lockwood fan beforehand because she - I don’t know if she does them anymore - but she used to do amazing reviews for the London Review of Books. And you think of the LRB as, you know, longform, sometimes sort of eccentric, but basically quite literary and serious, and she would just… go off on a tangent about foot fetishes, or whatever… and this was in the LRB and it was just… it was the best thing in the world, in my brain.

I actually had no idea that No One is Talking About This was going to come out, but then it had been shortlisted for Booker in 2021. And so… it’s pandemic time, so I ordered it online, which is really fitting, and then this hysterical hardback - which has this blue and purple cover with a rainbow going diagonally across it, and clouds at the bottom and sky at the top - arrives, and it’s so brilliantly ugly, you know, it’s just perfect for the book. It completely gets to the heart of this idea of the portal being this surreal space and, you know, and somehow that there’s a real world outside of it.

JW: I must confess, I came across the book - well, I read the reviews and I heard about it when it came out - but I read it because I knew it was going to be Jo’s selection today. Can’t deny that. I was going to say - I don’t think there was anything particularly, I hadn’t read it because of, you know, I didn’t like the sound of it or anything. Just that the books you read, what you end up reading, there’s quite a lot of luck… because there’s a lot of books out there, as you may have noticed. And also, because I review as well, so quite a lot of the books I read, I read because I’ve been asked to read them.

JH: With excellent taste, James.

JW: Yes, in this case. Fantastic. Absolutely thrilled to have this recommended. I absolutely loved it. So, do you want to tell us a bit about it, give us a basic intro?

JH: Yes. So, No One is Talking About This takes place in… fairly contemporary, I would say probably 2018-ish era. Doesn’t feel like the pandemic has really happened?

JW: No. Trump’s around, isn’t he?

JH: Yeah. Trump’s around. And it’s got two halves. And the first one is about this kind of internet personality who’s asked to speak at various conferences… in the British library or, you know, weirdly at one point, in Ireland. And she is the sort of person we would describe as being ‘very online’. She refers to the internet as ‘the portal’, and the first part of the book is this kind of deluge of memes and just like, things you thought you forgot that you saw on Twitter over the last five years or so. And then the second part flips and she’s kind of brought into the real world because her sister has a baby who’s born with Proteus syndrome, which is when a baby grows far too fast to support itself. And you see how all the philosophising at the beginning ties into this extraordinary reality at the end.

JW: You think it ties into it, or that the reality is that, in the end, that she’s ill-prepared for something quite so real from what’s gone on, on the portal?

JH: Yeah, that’s an interesting question. I mean, I always thought that the choice to give the baby Proteus syndrome was kind of parallel to her experience on the portal, in the sense that she’s got way too much stuff - this kind of overload that’s growing and growing in her, in the same way that this baby is growing. And because this baby is - spoiler alert - is doomed to die after something like six months, what she’s able to do with all of the information that she’s acquired, is basically just give it the whole world from all this stuff that she’s learned online. And, fair enough, some of it is really absurd and inane and stupid, but I think the kind of conflict that she comes into where she has to pass out what truly means something, means that she’s able to give it the best possible parts. And in this way, this baby can have a life because of the time she spent on the portal, but equally, she can have a life because of this baby who’s brought her out of it.

JW: Yeah, I must say I read the second half, I must say slightly differently than it essentially that she was… I mean, the first half is fantastic. I mean, it’s just… it’s really funny, full of, you know, the idea that we’re living in a stream of consciousness that’s not even ours. It’s, you know, so we’re in the blizzard of everything, she refers to the first sentence - ‘we’re living in this blizzard of everything’. There’s lots of good jokes. She tries to sort of go along with things. ‘Capitalism. It was important to hate it, even though that was how you got money.’ All that stuff. And there’s one bit, when she’s really, really trying hard to hate the police… but unfortunately her dad’s a policeman, so that makes it a bit trickier.

And, I mean, it just not only talks about, you know, what the internet’s like, but it really shows you, and it’s fantastic. And then in the second half, from my reading of it, something quite real happens that isn’t… slightly to her puzzlement, isn’t, you know… even though everything’s on the internet, this isn’t… nobody is talking about this.

JH: Yes. That’s the puzzle.

JW: Yeah and… I think she says at one point I think - this is the narrator speaking, or, well, it’s not exactly the narrator because it’s third person - ‘If all she was was funny and none of this was funny’ - which is her sister’s very sick baby - ‘If all she was was funny and none of this was funny, where did that leave her?’

And I think that the book sort of confronts that a bit in the second half. Because I mean, rather heartlessly, I think the second half’s less… I mean, it’s just about a baby dying.

JH: Well, this is actually, I was going to ask you this because I think there is… there are people who really loved this book and then there’s an equal amount of people who were really confused by the flip and it left them completely cold. And I have always been so puzzled by why that is, because I think the second half only enriches the first one. And I’m like, ‘You fool! How dare you?’

JW: I must say annoyingly, you make quite a good case for that, but I’ll stick to my little case for now. Which is that I think she acknowledges that… that she’s not playing to her strengths anymore. That bit about, you know, ‘if this isn’t funny and I’m funny… what do I do now?’ And I think she’s aware of the fact that the internet in the second half - both in the writing but in the experience - this is not what she’s for, in a way. She’s not playing to her strengths anymore. And part of the book is about the fact that the internet has made us, made real life, not our strengths anymore. But at the same time, she isn’t playing to our strengths anymore. There was a headline in the Onion, the satirical magazine, after 9/11, which was, I think, ‘Shattered Nation Longs to Care About Stupid Bullshit Again’. And, you know, just three weeks ago we cared what Britney Spears wore at the MTV Awards, and now we are… we’re talking about life and death and family. And in a way I think, part of this book is… a yearning to care about the stupid bullshit again.

JH: Yeah, that’s very true. There’s the part where she talks about the age gap between her and her sister, and she says that basically her sister is kind of brought up just at the point where seriousness kicked in. You know, just at the part where people stop stumbling out of cabs, you know, with two hours in their bags and wearing Juicy Couture track pants. And there’s a new kind of… But I find that really, really fascinating as a theme in this book as well, because, something that kind of puzzles me about it - and part of why I chose it as my favourite - is that I think it’s a really great experiment into what is actually important, not just because of the plot, but because all the sort of paraphernalia of the internet that it refers to, so minutely, is stuff that was in the culture at the time, you know, like Harambe the gorilla or what have you, that felt like… it was everything to us. We were seeing this… on our phones every day and discussing it and whenever Trump said something stupid, we were there. But how long does that last, you know? When I reread this book, I realised that I recognized fewer of the memes than the first time because it was less fresh and that I probably need a set of footnotes in the back to be able to.

JW: Thinking about that if there was an edition of this in… 50 years, or even 10 years. I mean, it is going to need a lot of footnotes.

JH: But then I, it’s kind of interesting with what you are saying because… I think the first time I read this and I was reading all these memes, there was this kind of grin of recognition and I was like – ‘Ha! Yeah, I remember that. I remember laughing about this on Twitter’. And this time the ones I didn’t recognise, I read them so much more seriously. I was scouring my brain and I was like, ‘What is the meaning of this? What’s the relevance of this? How do I fit this into my life again?’ When, at some point, it was just stupid bullshit to me that I was… wasting time scrolling over. So that transition of, I guess, levity and ease into the real matter of life and how you pass it is kind of inherent in how this book moves through time for its readers?

JW: No… and it does do that brilliantly. As I say, I feel pretty heartless in a kind of, you know, someone who’s been on the internet too long kind of way, to say that… the second bit about the death of a child, is sort of almost less engaged. I mean, it’s just… it’s perfectly done, but I’ve read books like that before. I’ve never read a book like the first half of this, actually. It was extraordinary and it does… it does make you realise what it’s doing to us. For good, I mean, she, she’s not completely anti-internet, is she? But… she is aware of what it’s doing, you know, the idea that we’re sort of disappearing into this common understanding of things, where we all have to… There’s one bit she’s talking about, you know, every few days you have to decide who we’re all going to hate now.

JH: Yeah.

JW: Then that sort of passes away and then we hate someone else and it could… it could be for some massive war crime or it could be because of their stupid recipe for guacamole.

JH: Yeah, exactly. Have you by any chance looked her up, because she is similarly active on Twitter in the way her protagonist is?

JW: Yeah. No, she is. Yeah. She, she does a famous… Didn’t she want… a Paris Review saying, ‘So what did you think of Paris?’

JH: Yeah, exactly…

JW: So that’s how she made her name and I think she has given talks and things, hasn’t she?

JH: Yeah, she has.

JW: So, this is her world. But it’s a world that when she comes to write about it, she obviously can see from the other side and, and the second bit’s autobiographical. Although I think that did happen to her, to her sister and to her.

JH: I just actually can’t get over the fact that you weren’t moved by the baby. I’m sorry, James. How, how can you?

JW: Well, no, I was. I was moved. I was moved by it. But no, that… that’s unfair. I was moved by it, but I was, I was aware of… I was being made to be moved by it, you know what I mean? It just felt… like a good novelist treating a sad subject seriously and properly - and interestingly, and affectingly - but still more like… what novels are like, in a way, and what novels do with that sort of subject. Rather than the first bit, which… It had to be that way round. But it did mean, I think, that the second half… As I say, she is aware that in the second half she’s not playing to her strengths, and I think she isn’t quite.

JH: Hm. I think, I think yours isn’t an uncommon view. It’d be great to do a poll of people who have read No One is Talking About This and see… do they prefer the first half to the second? You know, is it equal parts?

JW: I mean, I have to say the first half… in the first few pages, you are… disorientated. I mean, I did… my rather scholarly notes at the side read, ‘What does this mean?’ quite a bit. But then you, but then you kind of get… then you get into it.

JH: Yeah, you do. And you’re kind of carried by it. But I had exactly the same thing. The first point was when she referenced stimming, which I should know because I think half my friends have had an autism diagnosis by now. You know, the whole world’s autistic at this point. And I was like, ‘I don’t remember what stimming is’. And I looked it up online. I got this really serious… set of definitions of what stimming could be from Google. And then at some point I was like, ‘Oh God, do I do it?’ And I was like, ‘No, no. Go back to the book.’

JW: Stimming, we should say is, is a sort of sort of rocking movement or something or any, anything sort of hypnotic that… that you do. And I think… what we haven’t emphasised enough is just how many fantastic one-liners there are.

JH: Oh my God.

JW: Just how many good jokes. I mean, it’s…

JH: It’s incredible.

JW: Some of is quite stand-uppy, isn’t it?

JH: I think, well, I mean it’s interesting because I think there are two ways that she does it. And one of those ways is really stand-uppy, like when she’s… in bed with her husband and she’s hypothesising that she’d be able to bring Trump down by seducing him and having sex with him. And her husband’s like, ‘Don’t be ridiculous’. And then she… whips her top up and she’s like, ‘Do you think he wouldn’t go for these?’ And that’s like the end of the argument. But then I think there are other parts of it that actually feel almost… like a Russian novel to me, that are incredible. Like when she’s talking about the Czech girl on the train who’s kissing her boyfriend’s wrist like it’s the first strawberry of spring… Which is just such incredibly exquisite prose.

JW: Okay, Jo. Well in, in the end, we both loved this book in slightly different ways, but both loved it. And why do you think it was Booker-shortlisted, obviously deservedly as far as you’re concerned?

JH: I have two theories, and the first one is probably not true. So, Patricia Lockwood, her father is actually a priest and before she wrote this book, she wrote one called Priest Daddy, which is kind of a quasi-memoir. And on the judging panel, in the year that her book was shortlisted - No One is Talking About This - one of the judges was Rowan Williams, who was Archbishop of Canterbury.

JW: Former Archbishop of Canterbury…

JH: There you go. The clear one. The obvious choice. And I… obviously Lockwood and Rowan would’ve never met or discussed or anything. But I like to think somewhere in my mind that Rowan Williams is just a really huge fan of Priest Daddy. And he was arguing Lockwood’s bit in the meetings. Like, you know, ‘She’s one of us!’ Er, which is probably not true.

But then, the second reason really, and this is why I think actually it was an incredibly cowardly thing to have not named this book the winner for 2021. I think it was really the only choice. In part, I’m going to steal your homework here a little bit, partly because really, at least the first half of this book, no one has written like it before. No one has, you know, managed to distil the absolute mess of the internet in a form that preserves the idea of this portal, you know, you get a sense of it, you get a sense of why it’s such a bewildering and wonderful and strange and brain-rotting place to be. In a way that makes total sense of it, you know? And that gives you a kind of… in a way that you can zone out and see it for what it is. You know, people hold their phone in their hands every day and they’re so… in it.

And I doubt that… you know, that year a lot of kind of internet novels were coming out and I think the most… famous comparison to Lockwood’s book is Lauren Oyler’s… God, I can’t remember what it was called. Lauren Oyler also wrote an internet novel that year, but it was dry and it was so polemical and it moralised so much, it was just boring. Sorry, Lauren, you know, if you ever hear this. And what Lockwood’s done, again at least in the first half of this book, and I think convincingly in the second as well, is basically broken into a whole new form of literature that addresses this massive aspect of our contemporary life. And she’s done it buoyantly and with such style and… with such a kind of a grasp of her craft. I think it should have won.

JW: And really, really funny. And also, just to add to that, I mean, it’s easy to do a polemic against the internet, isn’t it? But what she does really, really well is our love / hate relationship with it. She does the love bit just as much as the hate bit. When she’s away from it, she’s slightly, you know, bereft.

JH: Yeah. And I think that’s how we… how we all feel. There’s that amazing point where she asked her husband for a kind of safe that takes the shape of an encyclopaedia to lock her phone inside, so she can’t access it before bed. And then, after about four days or something, she’s trying to break into it. She’s trying all these different passwords on it and she gives it to her husband and she screams, ‘I need my phone! I need my phone!’ And he unlocks it with the numbers. 1, 2, 3, 4. And it’s… one of the best bits of that book because you… you want to be away from your phone. You want to be away from the internet. You don’t want to know what’s happening. But you do. You need to. You have to. It’s so simple, right? It’s like that passcode. The access is so easy. But it’s so complex at the same time.

JW: Okay. I’ve gone for Patrick McCabe’s The Butcher Boy, which was shortlisted in 1992 for the Booker Prize. I think slightly surprisingly, because he wasn’t well-known at all, then, I think obscure would be the word. And there were some big names around on that list, Ian McEwan already quite big, and it ended up being a shared winner between Michael Ondaatj’s The English Patient and Barry Unsworth’s Sacred Hunger.

It was after that that the Booker people brought in a rule that you weren’t allowed to share prizes, until the judges in 2019 rather notoriously completely ignored that and insisted on sharing it between Margaret Atwood and Bernardine Evaristo.

JH: Lest we forget.

JW: Lest we forget. And that might be a subject for a future podcast story. Or it might be something we never talk about ever again.

But anyway, it’s a book which is narrated by the main character Francie Brady. Who is, what he calls himself, the one and only Francie Brady. Which is kind of true because I’ve never read a book like this before. I have since because… but they’ve all been by Patrick McCabe. He specialises in what I think is affectionately known as bog gothic. Which is small town, a small town in Ireland, a main character who is to a greater or lesser extent mad - normally to a greater one – and ends up doing something horrific. And that’s what happens here in this small town in the early 60s in Ireland.

It’s fair to say, Francie doesn’t have a happy childhood. His dad is a violent, abusive drunk. His mum, possibly as a result - or possibly anyway - has mental problems of her own, and the house is a complete mess. The trouble really begins when a boy called Philip Nugent moves into the town. And he’s come from England and he went to a private school, he’s got a blazer and everything. And Francie becomes sort of obsessed with him and his enviable middle-class life, you know: two parents who love him, a clean house, piano lessons, and so on - except that he can’t ever admit that he’s envious. So, I think one of the things the book does brilliantly is that Francie, at the same time, knows things and refuses to accept the fact that he knows them, including his envy of Philip.

And he, Francie, and his friend Joe con Philip out of a collection of comics, and Mrs Nugent comes around to complain at the Brady’s and refers to the family as ‘pigs’. And this absolutely sears him to the heart. Now he does his best to wear it as a sort of badge of honour, but really it’s a deep source of shame. A shame that increases considerably when he, after a particularly bad family row, runs off to Dublin. And when he comes back, I think a couple of weeks later, his mother - whom he had vowed to protect and look after always, all the days of his life - has committed suicide. At which point he breaks into the Nugent’s, badly defiles their house, including with his own excrement, and is taken off to a reform school. Where he is abused by a priest and, possibly worse as far as he’s concerned, gets a letter from his old friend Joe, which clearly suggests that he is now friends with Philip Nugent. And again, this is something that he kind of realises and refuses to realise at the same time. And he still looks back to… he looks forward to when he gets out of his reform school and him and Joe will be doing what they always used to do. And then when he gets back to the town after that, obviously Joe’s nervous of him, doesn’t… really want to be his friend anymore.

What’s fantastic is, every time Francie… tries to sort of blend in. He’s got this kind of excruciating small talk, hasn’t he? And he’s sort of saying to the ladies, ‘Oh well, sure, that’s Christmas over for another year. Be quiet now to ‘til St. Patrick’s.’

And everyone obviously is just sort of nervously backing away from him, wondering what he is going to do next. Because… he does continue to be extremely violent. I think, from then on, I could easily summarise it by saying things go from bad to worse. They really, really do. And one by one all his consolations, like his friendship with Joe, but other things that he sort of thought, or pretended to think, were true, all of them are stripped away and in the end, he ends up attacking… well, I don’t think this is a spoiler because it’s on the very first page, its very first sentences, which I think is brilliant too.

‘When I was a young lad 20 or 30 or 40 years ago’. So even that’s… ‘I lived in a small town where they were all after me, on account of what I’d done on Mrs Nugent.’

JW: That ‘on’ is a fantastically Irish preposition, thing… Anyway, after what he’s done ‘on’ Mrs Nugent, he’s taken away to a psychiatric prison hospital, where he remains for the rest of his life. Now, this might sound, make it sound horrifying - and it is.

JH: It is.

JW: But it’s also quite funny, isn’t it? And it’s also, I think, which I also think is its main thing – it’s just heartbreakingly sad.

JH: It is sad, I’ll give you that.

JW: It’s partly because he never had a chance, and partly that determination to just always be cheerful. You know, he’s always trying to look on bright sides and, one by one, those bright sides just go dark. Dark and darker and darker. But I think the real, I think the real power of the book is we do have sympathy for him. And he’s not, he’s not a psychopath, is he? Because he’s got feelings, quite soulful feelings. I mean, some of the writing’s very lyrical. One of his great memories is, just him and Joe when they were kids, scraping the ice off a puddle. And then he revisits the puddle, you know, when he’s late, when he is older and he sees other kids doing it. And he says, you know, ‘This used to be me and Joe’s puddle’. And they say, ‘You told us that yesterday, mister. Go away.’

And Patrick McCabe has said, it’s not a naturalistic book, it’s not… realism. He calls it ‘the social fantastic’. Good phrase. But I think it is. I think it has got a psychological realism. I think it comes together as a character portrait, and that makes it even more alarming. So, you know, the first time I read it, it blew my socks off completely. When I reread it for this, it blew my socks off again. I just wondered where you stood, socks-wise?

JH: They were definitely blown off. I agree with you that the tragedy of this book is that you absolutely can sympathise with Brady, to various extents. I mean, I have to admit about halfway through, I found myself wondering just how far my sympathy could go, because this book really is horror after horror. It piles up very thickly. And at some point I kind of thought, you know, at what point does your sympathy begin to wear away? And I think it does a little bit, but just the right amount - so that you never condone what he’s doing, but you know why he’s doing it. And…

JW: And if someone just loved him, would it all have been okay?

JH: Well, do you know what, that’s interesting because towards the end when Mrs - I don’t know whether it’s Connolly or Connoloy –

JW: Connolly. Yes.

JH: Connolly. She comes round to scrub the house so that he has somewhere to live. And maybe by that point he’s so far gone that he can’t really recognise it. And, of course, he’s seen her talking to Mrs Nugent, which he sees as a kind of form of betrayal as well. But I think that was a sort of chance. And I… when I read that, she’d sort of scrubbed the house, I was like - well, I’d already seen the summary of the book, so I knew there was no way in hell - but I had this brief flicker of hope that, you know, this semi-maternal figure who he’s spoken to so many times in the shop, he’s gossiped with the ladies with her, you know, that maybe she could somehow save him. And I think the other thing that maybe made me think that was that, you know, quite late in the book, he’s always got that image of a snowdrop that represents the potential beauty of the world to him. And then… I don’t know… I think the book is full of people who at various stages - often quite ineffectively, but in the best way they can - try to love him. You know, his father visits him in boarding school, somewhat self-servingly, but tries to, you know, extend a hand of friendship, but it’s too far gone.

JW: His father tells him about, you know, okay, your mother and I fought quite a lot-

JH: Yeah…

JW: Towards the end, but, but we had this beautiful honeymoon in this boarding house in-

JH: And that’s a lie, yeah.

JW: -Donegal. And you know, people loved my singing and we prayed the rosary together on the beach as well. And this becomes one of his consolations as well, at least he’s got that. And then he visits the boarding house and speaks to the landlady. And…

JH: And no, but… if he had believed in this idea that his father tried to put together, that… once upon a time he and his mother had been happy and they had a great honeymoon, and if Francie in that moment had thought to himself, ‘I’ll pin my hopes on that’, you know, had never run away and gone to the boarding house to find out it was a lie and instead had gone back to his father, which he eventually does… and gets a job and tries to have this sort of happy domestic life.

JW: Yeah. But it’s not quite enough because there’s also one thing… I don’t know how much we should spare the listeners, but basically his father dies in an armchair with a heart attack. He just mentions that ‘my dad was very cold’, but then he carries on, he keeps on talking to his dad. He goes out to buy drinks for his dad. And… eventually, you know, the authorities break in and we just hear the words ‘Yes, he’s riddled with maggots’.

JH: Yes.

JW: So, his dad’s basically decomposing on the chair. While, but again, while he’s trying to put on this brave face. And it’s after that, that he goes to the boarding house and, in fact, the landlady uses the phrase, you know, there’s a drunken pig, so the word ‘pig’ again.

But even then there’s a tiny bit of sympathy. There’s quite a small thing, because his dad grew up in an orphanage in Belfast with his brother, and his father seems to have had his, you know, what happens to Francie, too. Which is, he remains convinced that his dad’s going to come up and come and pick him up any day now. And his dad obviously never does. And Francie’s dad turns into what Francie’s dad turns into. But when the landlady tells him what a drunken pig his dad had been on the honeymoon, he says, and he attacked that poor priest from that orphanage in Belfast. So presumably that was someone who’d mistreated him there. So, there’s just this endless cycle. Even one of the cops says, doesn’t he? The police sergeant who takes him away for one of his many offences, ‘You know, he couldn’t have been any different’.

JH: Yes. But now I’m depressed, James.

JW: No, I mean, it… it is a cycle. But it’s not just that, is it? It’s… there’s something about Francie that’s… I mean, I’m not a fan of this phrase at the best of times, and possibly not in the context of Francie Brady. Life-affirming. But sort-of? He just will not give up until he has to give up. I mean, he does end in complete defeat.

But… I think most of us would’ve been completely defeated a long time before. And he, every now and then he sort of gets his bag, you know, his shopping bag together, goes down, has a word with the ladies, makes his excruciating small talk, buys a few things.

JH: Yeah, I guess that’s because he’s not entirely tethered to reality.

JW: No, not in the slightest,

JH: And that’s the only way that he can go on. So, I don’t know if that’s like… how hopeful a message that is. I mean, I really-

JW: How hopeful would be overstating it, certainly.

JH: Well, I don’t know how life-affirming a message that is because it’s-

JW: It’s not life-affirming but I don’t think the message of the book is life-affirming-

JH: But that Francie is, perhaps…?

JW: But there’s something about Francie that is, he’s sort of irrepressible, isn’t he?

JH: Can I ask you something really because… it may be a flawed question - not everyone agrees that you should ask this question of a book - but I was kind of trying to think… What is it for, you know? Why does this book exist now that I’ve finished reading it? Because… actually if I had to, if you gave me a choice: did you like it or did you not like it? I’d be forced to say that I liked it. Like isn’t really the word, but there’s something about it that I admire. But I can’t put my finger on what it is. And there’s an introduction in my version that… references the fact that some people see it as a sort of allegory for colonialism in Ireland. You know, other people think that’s entirely not the case. I was trying to think… maybe this is interesting to me because it’s a compelling psychological portrait, but I cannot put my finger on what it is about this book that meant I finished it… and wanted to have the experience of reading it - and I’m glad I did - but I’m still not sure why.

JW: No, it is a most peculiar of entertainment. I’ll give you that. I’ve never heard that colonialism theory before. My theory on the possible allegory would be different, actually – it would be Ireland itself tells itself just as stupid consoling myths as Francie does. And that Ireland is, I think it’s quite… it’s quite angry with Ireland, I think. Michael Collins turns up a bit, doesn’t he, everyone claim some sort of link to Michael Collins? This is early 60s, so it’s still the sort of heyday of Catholic Ireland. Towards the end there’s the Cuban Missile Crisis, but they think Our Lady is going to protect the town, and so on. And that Our Lady protecting the town against… nuclear weapons is possibly a bit like… the fact I used to have a friend called Joe who’ll protect me from all the terrible things that… I could potentially do. So that was my only allegorical reading. But didn’t you think the prose is fantastic and sometimes quite funny?

JH: I don’t know, maybe this is kind of like-

JW: I’m trying to think of an actual joke.

JH: Yeah, pick one.

JW: There’s no Patricia, there’s no Patricia Lockwood for gags, I must say. So, okay. I don’t know, really. They’re just this… So, it starts off with him in hiding after he is done what he’s done on Mrs Nugent and he’s in this sort of hide that him and Joe built. Again, this is very important to him. Him and Joe built this fantastic hide and they used to have fun there. Obviously by this time he’s well on his own.

JH: ‘You could see plenty from the inside but no one could see you. Weeds and driftwood and everything floating downstream under the dark archway of the bridge. Sailing away to Timbuktu. Good luck now weeds, I said. Then I stuck my nose out to see what was going on. Plink - rain if you don’t mind!’

JW: You know what I mean? There’s something-

JH: You don’t think-

JW: Yes, but irrepressible. ‘But I wasn’t complaining. I liked rain. The hiss of the water…This is the life, I said.’ I mean, ‘this is the life, I said’. It is sort of funny, isn’t it? He’s… killed someone, horribly. The whole town’s looking for him. He’s in a hide. ‘This is the life. I said’. I mean… it’s heartbreakingly funny, but it is quite funny.

JH: I don’t know. I’m really struggling to see it. I think, I wonder if this is maybe… I don’t know. I don’t know what to pin this down to. I was about to say something dumb about like a generational difference and maybe I’ve been brought up in a way, or in an environment that sort of, as we were talking about with the Patricia, with the Patricia Lockwood, you know, is now taking things very seriously - but actually I chat so much bollocks in my life that I can’t really say that’s true. I think maybe it’s…

JW: We could explore the generational thing if you want. I think the one thing I’ve noticed in my reading time, generational, is that… almost the weird revival of the idea that books should be virtuous, novels should be virtuous. So, if you read reviews… We could chortle our socks off at 80s’ university reviews of Wuthering Heights or Jane Eyre, were being attacked for being immoral and not the sort of thing people should say or do, not edifying. But book reviews now use exactly the same sort of phrasing, really. And Patrick McCabe is not edifying, he’s not virtuous. But it’s fantastic. And books… should almost not be virtuous, would be an argument. Or the novel… it shouldn’t be what life should be like, but is… I suppose that would be my generational argument.

JH: Yeah. Do you know, I was thinking similarly to what you said about reading the first half of No One is Talking About This I had that with the McCabe. I’ve never read something that I couldn’t place in one kind of neat box in my head, after some thought, you know, and say definitively. Even if what I was thinking about it was sort of dialectical and, you know, it was like an either / or argument, but at least I could say that. But I am actually speechless over this novel. I, funnily enough for a podcast, have nothing to say about it other than I’m shocked.

JW: No… honest, that might be generational too. I’m not surprised you’re shocked, but I’m surprised that you’re this shocked.

JH: It might just be, you know, something really simple because all the reading I do is… for book reviewing or for podcasts or for academic work. And I’m very used to kind of reading things into a text or reading things out of a text and maybe this is flooring me because what it is, what all of this is leading to very simply is just Francie Brady as a character who is just so utterly convoluted and lifelike and, you know, such an extraordinary achievement to have placed in a novel. If anything, you read this book and you’re like, god! Writing like this exists and someone is capable of it. And the idea of Francie Brady is something that exists in the world and that is terrifying and extraordinary. And I hope it never happens to me, you know? But also, I hope it never happens to me but on some level I need to know about this sort of thing, not because… not for the reason that you watch horror films to kind of inflict terror on yourself, but because of the sympathy that is in the core of this book that you feel, I need to know because - how else would I find out? This is a safe way to find out about shit.

JW: I think it does, it does conjure pity and sympathy. And, to keep the sympathy going for him is… astonishing, really. And yes, you’re right. You know, you sort of root for him. You don’t root for what, for everything, he does, but quite a lot of… You don’t root for much of what he does really! But just for him to just… maybe… So maybe Joe would just say, ‘Yeah, okay, Fran, let’s be friends again’.

JH: But can you blame him…?

JW: No, absolutely not. No, God no. If we met him, we’d… you’d back away nervously at the very, very least, you know? Absolutely. And he, you know, he can go off on one at any point.

JH: You just want him to get better.

JW: And also, there’s that heartbreaking phrase, ‘That was the best laugh yet’. He kind of pretends that things are funny. You know, ‘Joe said that he didn’t wanna be my friend anymore. That was the best laugh yet.’ I dunno. I absolutely, I think it’s… I think it’s marvellous and I think he’s marvellous.

JH: So, James, I can see why you love it, but why do you think this book was shortlisted for the prize?

JW: I mean, obviously it’s difficult to read the judges’ minds, but I’d rather hope that it was that sense that I had that there’s really nothing like it, or there hadn’t been much like it. I mean, the paperback I’ve got has got on the front Roddy Doyle saying, ‘Brilliant, unique - reading fiction will never be the same again’. And I think that’s a sense for quite a lot of people who read The Butcher Boy is this, ‘What the hell is this? I mean… where’s this come from?’ I mean, Patrick McCabe was a sort of school teacher himself in smalltown Ireland. He sort of got up at seven o’clock and just wrote this, you know, every morning apparently, and just wrote this in a bit of a splurge. And he came up with this astonishing voice and this astonishing series of events and I think it’s hard to read this book and not be in some way blown away.

JH: Yeah, definitely.

JW: For good or ill.

JH: Definitely.

JW: Well, thanks so much Jo. And, just before we go, we promised at the start there’d be ways for listeners to get involved. So please do like and subscribe to the Booker Prize Podcast wherever you listen to your podcasts. If you want to get in touch, you can leave comments about this episode at the Booker Prizes Substack, as well as the usual Booker Prizes social media accounts on ‘the portal’, as Patricia Lockwood would put it. And that’s, as you might imagine, Twitter, Instagram and TikTok, where we also publish and promote a whole host of fascinating articles and videos - it says here - about our books and authors.

JH: And finally, please do check out the official [email protected] where you can find long reads, interviews, features, and information about the upcoming awards, the International Booker and Booker Prizes. ‘Till next time, bye.

JW: The Booker Prize Podcast is hosted by Jo Hamya and me, James Walton. It’s produced and edited by Benjamin Sutton, and the executive producer is Jon Davenport in a Daddy’s SuperYacht production for the Booker Prizes.