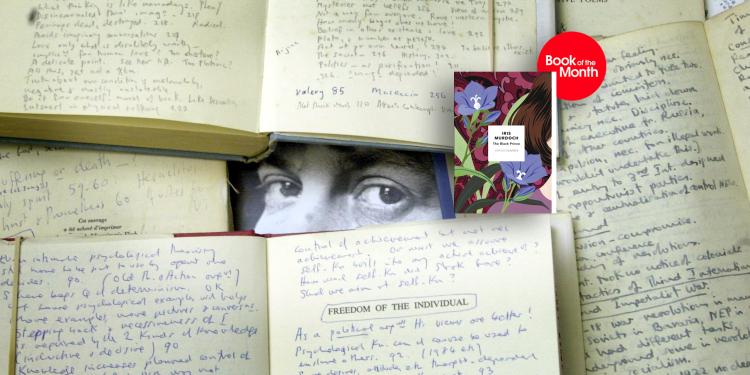

Book of the Month: The Black Prince by Iris Murdoch

In 1973, The Black Prince was shortlisted for the Booker Prize. Part-thriller, part-love story, it was Murdoch’s 15th novel and third recognition by the prize

Iris Murdoch wrote 26 novels, seven of which were nominated for a Booker Prize – including one winner – but with so many books to choose from, where should you start? Here, we select some of her best works

Reading Iris Murdoch is easy: you start by ignoring her reputation. At least this was my experience, having expected this high-minded philosopher-novelist’s books to be stodgy and remote, animated not by story or characters, but by ideas. This could not have been more wrong. Murdoch’s books are not worthy or dull in the least: dull is the opposite of what they are.

Her novels are clever, yes, and ambitious, yet they are not the opposite of popular fiction, but an elevation of it. Characters love and hate, are guilty and duplicitous, have secret sex while trying to be good: and all in a flurry of activity as their creator whisks them around the book like chess pieces on a board.

‘Literature is for fun, literature entertains,’ said Murdoch in 1977, and her books are funny, lively, as well as being ahead of their time in social issues, like her empathetic and subtle portrayal of homosexuality in The Bell (1958) or A Fairly Honourable Defeat (1970). John Updike likened her to Muriel Spark – both writers ‘reappropriate[d] for their generation Shakespeare’s legacy of dark comedy, of deceptions and enchantments’.

She wrote 26 novels – ‘Iris Murdoch’s annual novel now seems to have become an established British institution,’ wrote one critic on publication of her eleventh – so where is the best place to begin?

A Fairly Honourable Defeat by Iris Murdoch, first published in 1970, longlisted for the Lost Man Booker, 2010

The Black Prince (1973) – this month’s Booker Prize Book of the Month – may well be Murdoch’s best novel, a sustained achievement which feels like a culmination of her talents. It was shortlisted for the Booker Prize but didn’t win, against a very strong shortlist – The Dressmaker, A Green Equinox, The Siege of Krishnapur – all characterised by a blend of black humour and eccentricity.

This ‘celebration of love’ (as the subtitle has it) is as demented and twisted as any book Murdoch created. From the opening lines, where our narrator is told by his frenemy Arnold Baffin, ‘I think that I have just killed my wife,’ it doesn’t let up. The narrator is Bradley Pearson, a mediocre novelist who hates bestseller Baffin. He wants peace and space to write the book he is convinced will be his masterpiece – but life keeps rushing in. First, Baffin’s wife Rachel – who, after all, is not dead – falls in love with Bradley, though he is embarrassingly unable to consummate their relationship. Later Bradley does manage to achieve what he memorably calls ‘the anti-gravitational aspiration of the male organ’ – in a shoe shop, with Baffin’s daughter Julian.

Bradley is ridiculous – we don’t like him, but we recognise in him the ludicrousness of our own worst impulses, and the dreamlike series of diversions and frustrations that stand in the way of his goal. This is a recurring theme for Murdoch: the chaos that sexual love brings, how it both revels in selfish behaviour and drives people out of themselves. For a serious novel, as writer Sophie Hannah put it, The Black Prince seems ‘too brilliant, too purely enjoyable’.

The Black Prince by Iris Murdoch

Murdoch wanted her fiction to teach us lessons: often the lesson being about freedom, and how doing what you want will affect those around you

Murdoch’s fifth novel, A Severed Head (1961), is where her distinctive style first reached maturity. It shows the distilled essence of her appetite for the ludicrous comedy of life. It is full of sparky dialogue: ‘We’re not getting anywhere,’ the narrator’s wife says to him. ‘One doesn’t have to get anywhere in a marriage,’ he replies. ‘It’s not a public conveyance.’ And it is riddled with Murdoch’s characteristic sexual pairings: by the end almost every combination of characters has made a go of it.

It opens with concealment, the narrator Martin Lynch-Gibbon discussing his wife Antonia with his mistress Georgie. ‘How is Antonia’s analysis going?’ ‘Fizzingly. She enjoys it disgracefully.’ Deceptions and revelations pile up as new characters arrive and fall in love, and by the time our adulterous narrator starts arguing moral superiority with his wife’s lover – with whom he is also in love – having caught the man in flagrante with his own half-sister, the reader’s head spins. (It is not, by the way, essential to always follow exactly what is happening. The whirlwind is part of the fun. Martin Amis, reviewing a collection of John Updike’s essays, illustrated of Updike’s vast reserves of knowledge by observing that ‘he even knows what’s going on in a novel by Iris Murdoch’.)

And there is plenty more rakish fun to come in A Severed Head, featuring everything from a samurai sword to an unexpected gift curled up in a box. The novel is full of exaggerated love, and love was a prime component in Murdoch’s work: she saw real love as akin to goodness, and the question of goodness was her other driver. ‘I wonder if you have the faintest idea how good you are?’ Martin’s wife Antonia asks him. ‘I’m beginning to realise,’ he replies. ‘It hurts so much, for one thing.’

Cover of the first UK edition of A Severed Head by Iris Murdoch, Chatto & Windus, 1961

By the time The Sea, The Sea (1978) won the Booker Prize, Iris Murdoch’s themes – love, goodness, life versus art – were well established. This novel turned them all up to 11. Its narrator, former playwright Charles Arrowby, is her most monstrous narrator of all, and probably her most unreliable. Arrowby lives by the sea, where he cooks disgusting meals – boiled onions are a favourite ingredient, supplemented by ‘liberal use of the tin opener’ – and nurses his grievances.

We spot the real Arrowby not just by seeing through his grandiose self-image – nobody sane could think so highly of themselves – but also through what he admits other people say about him. A newspaper calls him a ‘power-crazed monster’; a woman declares him a ‘rapacious magician’.

The story is a stew of resentment, jealousy and even abduction, but it all feeds into Murdoch’s intentions as an old-fashioned moral novelist. Her husband John Bayley, in his memoir Iris (1998) wrote that she ‘hardly ever read a contemporary novel’. Murdoch wanted her fiction to teach us lessons: often the lesson being about freedom, and how doing what you want will affect those around you.

One aspect of this fanciful story may have been inspired by life: like Arrowby, John Bayley was what one journalist called ‘a famously experimental chef’, specialising in recipes such as ‘Boil eggs in an electric kettle and then use the water for Nescafé.’ Murdoch and Bayley lived in Oxford in a house ‘in an advanced state of neglect’, described as ‘a still life with sherry bottles and Pringles tubes’. ‘We’ve never been much for housekeeping,’ Bayley understatedly told one visitor.

Cover of the first UK edition of The Sea, The Sea by Iris Murdoch, Chatto & Windus, 1978

One day Iris Murdoch will write a novel that is like a novel all the way through. But how dull that would be

There’s no denying that Iris Murdoch’s books can be long: from the 1980s on, they mostly topped 500 pages. But she could deliver a satisfying story in as little as 160 pages, as we see in The Italian Girl (1964).

Many familiar elements are present here in refined form. The story is about Edmund Narraway, returning to England for his mother’s funeral, and the pace is (relatively) sedate: but there are still eye-opening and jaw-dropping things. Edmund needs money from his mother’s estate, and must contend with his drunk brother, Otto, one in a line of Murdochian resentful men. ‘I could have been a good man if I hadn’t married. Sometimes I think women really are the source of all evil.’

Alongside the brothers are the women: Edmund’s niece Flora, who has a secret she shares with him; Otto’s apprentice’s sister, Elsa; and the Italian girl of the title, the longstanding and long-suffering household maid Isabel. Edmund’s problem is that everyone wants his help. ‘You lead a simple good life. You help people,’ says one.

But Edmund is also the subject of mockery, when one character takes his goodness for a lack of passion. ‘Perhaps you don’t really like girls? Perhaps you prefer boys? But no – you don’t really like anything at all.’ Edmund’s jealousy of the other characters’ couplings makes this a perfect short example of how Murdoch animates moral dilemmas into farcical settings. (She co-adapted her novel A Severed Head as a West End comedy.) At one point in a race across an unstable landscape, Edmund wonders, ‘Was I pursuing or was I fleeing?’ Elsewhere, the Italian girl tells him: ‘I want emotion and pistol shots.’ You get all that here, and more.

Cover of the first UK edition of The Italian Girl by Iris Murdoch, Chatto & Windus, 1964

It was once said of Booker winner Kingsley Amis that he would only read books that began, ‘A shot rang out.’ In that case, Iris Murdoch’s The Nice and the Good – shortlisted for the very first Booker Prize in 1969 – would have been perfect for him.

It’s a murder mystery: the first mystery being whether there was a murder at all, as civil servant Joseph Radeechy appears to shoot himself in his office in Whitehall, London. At the end of the first sentence, a colleague hears the ‘indubitable sound of a revolver shot’. By the end of the fourth paragraph, he hears ‘running steps’ – and the game is on.

As always, there is plenty to chew on, with the eccentric cast of characters including a dog called Mingo: but this being a Murdoch novel, beneath the surface mystery lies another mystery, outlined by John Ducane, the lawyer who leads the investigation. He wants to be good – or rather to appear to be good. As a man everyone thinks is an upstanding citizen, he seems the polar opposite of Radeechy – who appears to have been involved in occult activity. But the title makes the point that niceness and goodness are not the same thing.

Often there’s a balance in Murdoch’s novels between reality and unreality, where prosaic settings are coloured by heightened emotions and exaggerated elements, giving them a fantasy-like flavour. And this may be the novel of Murdoch’s which most draws on traditional fictional styles – a philosophical investigation you can curl up with – but retains all of her individuality. Reviewing it on publication in 1968, the New York Times – calling it her ‘best, most exciting and most successful book’ – Elizabeth Janeway also said, ‘One day Iris Murdoch will write a novel that is like a novel all the way through.’ But how dull that would be.

Cover of the first UK edition of The Nice and the Good by Iris Murdoch, Chatto & Windus, 1969

The manic action that is such a delicious characteristic of Murdoch’s novels can make them so entertaining it’s hard to see the larger themes: such as how she sees love and art as the routes to truth. So her debut Under the Net (1954) is worthwhile not just in itself but as a starter course.

It opens with a tease – ‘When I saw Finn waiting for me at the corner of the street I knew at once that something had gone wrong’ – as we join the world of James ‘Jake’ Donaghue and his struggles with money and other people. But as Jake moves from self-interest to an understanding of the world around him, we see a linear character development that is clearer than in some of Murdoch’s later work.

The relative simplicity of the story, however, still involves four people in varying degrees of love with one another. (Murdoch once said that happiness was ‘to be utterly absorbed in at least six other human beings’.) It’s this tug of involvement, what it lets us see but also what it hides, that drives the book. ‘We all live in the interstices of each other’s lives,’ observes Jake, ‘and we would all get a surprise if we could see everything.’

Above all, Under the Net is a first novel of a meatiness and achievement that would make other debutants blush. It is an example too of how, in her books, a deep thinker like Murdoch allowed those characters who take life less seriously to escape unscathed. (See also Dora Greenfield in her 1958 novel The Bell, another good place to start.)

Iris Murdoch was a productive writer of 26 novels and five works of philosophy. The critic Francis Wyndham pictured her ‘seated between two massive piles of manuscript, moving only to write, one pile of empty paper, the other full, her industry phenomenal’. She worked and reworked her themes over four decades, forever seeking to perfect her art. ‘Every book is the wreck of a perfect idea,’ said Arnold Baffin in The Black Prince. ‘If one has a thing at all one must do it and keep on and on and on trying to do it better.’ In her 1974 novel The Sacred and Profane Love Machine, the mystery writer Montague Small ‘wrote fluently and fast, hoping somehow that each novel would excuse and rescue its predecessor’. Murdoch herself took the same view, according to John Bayley, and would be only halfway through a book before declaring, ‘Oh I don’t think this one is much good, but better luck next time!’

And Under the Net is where it all began. The story starts here.

Cover of the first UK edition of Under The Net by Iris Murdoch, Chatto & Windus, 1954