Opinion

Where did Timothy Mo go? Revisiting the Booker author 'who got away'

Part of a golden generation of writers in the 1980s, Timothy Mo was shortlisted for the Booker Prize three times – then dropped off the radar. But his books deserve fresh attention, says Rebecca Liu

‘We were correct to think that we had no control over our destinies,’ thinks hotelier turned guerrilla fighter Adolph Ng in Timothy Mo’s The Redundancy of Courage, as he and his soldiers flee from invading forces, spar with the enemy, patch up the wounded and leave the dead behind. In Mo’s three Booker-shortlisted novels, characters are swept up in the currents of history, dogged by forces beyond their control, and become the playthings of gangs, empires, and warring political powers. They may have convictions; they may have dreams; they may only care for their survival. No matter – history comes for them in the end.

It is somewhat ironic, then, that Mo is now considered, at least within British literary circles, the writer ‘who got away’. Born in 1950 in Hong Kong to a British mother and Chinese father, Mo came to Britain as a child. Previously a journalist, with stints at the Times Literary Supplement, the New Statesman and the Boxing News, he turned to fiction in the 80s with astonishing success. Three out of his first four novels were shortlisted for the Booker Prize, and he was hailed as a formative voice alongside contemporaries Martin Amis, Kazuo Ishiguro, Ian McEwan, and Salmon Rushdie.

Then the disappearance. Shortly after his third novel was published in 1991, he left his publisher, and in the words of the Times, ‘fell out with just about everyone’, before moving to Southeast Asia. The friend who introduced me to Mo’s novels wondered if the author would have chosen differently had he won the Booker. Having read some interviews, I think not. Mo, with a distinctive sense of his centre, seems unruffled about being on someone else’s periphery. ‘People like a mirror; they don’t want a window,’ he told the Independent in 2000. ‘So I’m right on the margin now, in my treatment and my subject, but I firmly believe I’m writing about things that will be seen to have been significant, 50 years down the line. It will move to the centre as every year goes by.’

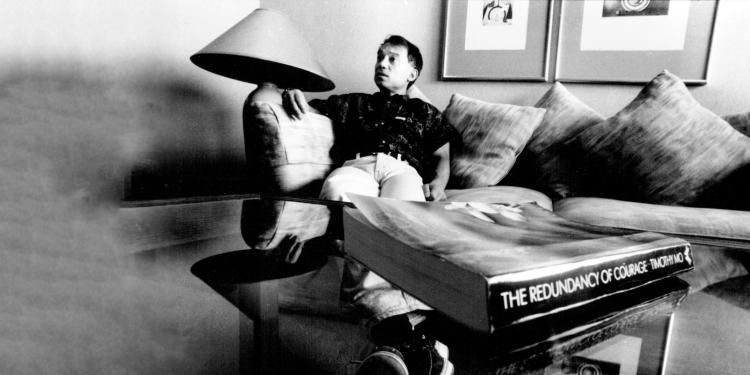

Timothy Mo with his shortlisted novel The Redundancy of Courage at the Booker Prize Ceremony 1991

© Rebecca Naden/PA Images/AlamyMo chafed against being labelled a figurehead, or a “Chinese writer”, saying, “I know nothing about Chinese culture”

Mo is best known today for his second novel, Sour Sweet (1982) which follows a Chinese family in 1960s London. Four years into living in the UK, the Chens have settled ‘long enough to have lost their place in the society from which they had emigrated but not long enough to feel comfortable in the new’. The pragmatic Lily lives with her meek husband Chen, their infant son Man Kee, and her sister Mui. Money is a struggle: Chen earns meagre wages as a waiter in Chinatown. Though Lily, like many first-generation immigrants, has big dreams for her child, and it is for his future that the family pulls together to start their own takeaway, gritting their teeth through back-breaking labour, insolent customers, and an unwelcome tax man.

The novel is a wry comedy: the food the Chens sold ‘bore no resemblance at all to Chinese culture’ but, to Lily ‘provenly successful: English tastebuds must be degraded as their care of their parents’. Yet an undercurrent of melancholia runs throughout. ‘In the UK, land of promise, Chen was still an interloper,’ Mo writes. Chen feels ‘like a gate-crasher who had stayed too long.’ Meanwhile, Lily drives through Oxford Street on her way to Chinatown in the novel’s stirring conclusion. The department stores speak ‘to her of wealth and elegance that she knew now she would never have’; seeing a glimpse of her reflection, she is shocked by ‘the look of bitterness and self-pity on her face’.

Upon its release, critics praised Sour Sweet and its deft depiction of London’s Chinatown: the travel agencies, hidden alleyways, fortune tellers, and special banquet rooms in multi-story restaurants. But many assumed Mo to be writing from life, and he himself an emissary representing the British-Chinese. The New Statesman deemed it a ‘brilliantly observed study’, while an interview with Mo in The Times was headlined ‘Making the Chinese Scrutable’. Mo chafed against being labelled a figurehead, or a ‘Chinese writer’, saying, ‘I know nothing about Chinese culture. It is as hard for me to write about things Chinese as it must have been for Paul Scott or for J. G. Farrell to write about India. I’m a Brit,’ and later spoke of feeling the pressure to ‘stay in my box’.

It’s possibly why Mo’s next novels were such a break from his earlier fare. An Insular Possession (1986) is a historical epic following white Americans in southern China before the first Opium War, combining narrative fiction with (fictional) reportage and letters. Meanwhile, The Redundancy of Courage is a war novel, set in Southeast Asia, that documents brutalities with merciless precision. The move confused some critics – one wrote of Mo swapping ‘quaint ethnic vignettes’ for ‘violent polemic’ – and might also explain why they have not found the same canonical status as Sour Sweet. Though strip away Sour Sweet’s breezy comedy, and one can see the themes that will occupy Mo’s later novels: the creeping allure of violence, the convulsive rise of empires, and that agonising point at which individual agency has no bearing on the dynamism of history.

Sour Sweet by Timothy Mo

An Insular Possession opens with a description of an unforgiving and turbulent southern Chinese river that ‘impedes native and foreigner alike’, winds ‘a sinuous course through lazy, rumpled hills’ and is home to prowling British and American trading ships. Gideon Chase and Walter Eastman are two young American clerks at a trading house. Strictly sequestered from the local Chinese population, the duo spend their days chatting shop, traipsing around their quarters, and secretly learning Chinese – doing everything, it seems, but work.

For all its length – my edition came to 723 pages – one could leave An Insular Possession wondering what exactly had transpired. Much like the turbulent river in its opening, An Insular Possession rises and falls with a hypnotic, languorous verve. We are lulled into descriptions of parties at the stately homes of expatriates; hunting expeditions; one memorable night on a riverside pleasure boat. Chase and Eastman are opposed to the opium trade, though differ in the degree to which they’re willing to grant humanity to the Chinese. As the conflict between the British and the Chinese ramps up, Chase and Eastman become drawn into the war, and violence emerges with greater frequency.

Yet that final conflagration never comes. The war is instead conveyed through the novel’s different prose forms – reporting in newspapers, letters between friends – giving distance to the heat of the action, and, as argued by literature scholar Elaine Yee Lin Ho, offering a metanarrative on the making of history itself. The British outlet Canton Monitor makes a staunch case for aggression, prompting Eastman to start his more conciliatory American paper. The discursive scuffles between the rival editors are often filled with more heat than the descriptions of the march of colonialism unfolding at their feet.

If it had assumed a different point of view, An Insular Possession could have been a very different novel: about the arrival of men speaking unfamiliar tongues, wielding devilishly powerful weapons; about the sickly aroma of opium wafting over one’s homelands; of the countless bodies that fought and fell in the losing side of a war. In today’s climate, a novel centering on white characters in the Opium Wars might invite some (understandable) fatigue. Mo’s descriptions of the odd Chinese character tends towards caricature; seen through the eyes of his white characters, they are contemptible and pitiable, barely human. It is almost as if, after being branded a chronicler of amusing vignettes about Chinese immigrants in Britain, the author turned around to spin a yarn about white settlers in China to assert his skill as a fiction writer, the boundlessness of his imagination and his facility with different prose forms.

If the Chinese are inscrutable in the novel, the English, however, are scrutable, and not always flatteringly so. We can see petty, mewling spite as the Canton Monitor rails against the ‘saucy mandarins of Canton’, lamenting ‘the city was ours! Only imagine – ours we say!’ Much like how the novel takes the form of a historical epic to then play with its constraints, it also takes the reader abroad to then reflect on the mother country; we see the idiosyncrasies of the English, the dark toll of colonialism, and violence lurking behind the respectable veneer of market liberalism. As the young Chase says, looking onto the inlet of the world he now calls home and lamenting the opium trade: ‘What energies, what talent, must there be in that teeming mass of humanity which is now so wastefully, so wilfully misdirected!’ To which the older, and more cynical, Eastman replies: ‘What markets! […] What fortunes to be made!’

An Insular Possession by Timothy Mo

Much like the turbulent river in its opening, An Insular Possession rises and falls with a hypnotic, languorous verve

Violence does not lurk in the margins of Mo’s third novel, The Redundancy of Courage (1991); it is splashed on every page. A fictionalised retelling of East Timor under Indonesian military occupation in the 1970s, it is written from the perspective of Adolph Ng, a Chinese businessman living on the island of Danu. When Danu’s neighbours – referred to as the malai – invade, he quickly witnesses a massacre on a pier. ‘The shots had smashed the victims down dead, face-first, but they had not fallen in the sea,’ Ng says; ‘after the first few the executions ceased to have the same impact’. The bloodshed doesn’t let up. As Ng is drawn into the FAKOUM independence movement, there are descriptions of tortured prisoners; of bodies convulsing in makeshift medical rooms, and a startlingly brief admission by Ng of preying on the young boys who join the guerrillas.

Is it torture porn? The Redundancy of Courage is certainly concerned with probing the limits of what humanity can bear: the extent to which the body can be rendered a brute weapon, the mind numbed to atrocity. But alongside these concerns is a deeply human story about Ng and his friends and their hopes, vulnerabilities, and shared moments of grace (many parts of the novel – such as the massacre at the pier – seem partly based on historical testimony.) That none of them meet good fates is almost a given, and there is an especially terrible moment near the end, when Ng meets a FAKOUM minister dispatched to New York. The minister tells Ng it is in New York where the results of the conflict will be determined, and where it also began. Ng first thinks him to be ‘egocentric’ but then ‘he changed my understanding for ever’. The minister tells Ng that the deep-water channel off Danu is key for shuttling nuclear submarines, and thus a valuable asset in the Cold War. The Americans, he continues, ‘didn’t want a left-wing government sitting on the canal-bank’ and thus supported the invasion. Then, ‘he smiled; there was rage and misery in that smile. And I understood at once the implications of what he’d been saying. That was why it all happened.’

The reader, having emerged from hundreds of pages describing the intimate hell of war, inevitably identifies with this rage and misery. If An Insular Possession considers a historical conflict from above, with developments tracked in newspapers, The Redundancy of Courage takes us into the theatre of action, making no concessions to war’s miseries, leaving the reader with a newly enlivened sense of horror about how games played by the powerful can leave so much devastation in its wake. That I was able to leave the novel with a sense of – brittle, appropriately cynical – hope is testament to the transcendence of its final pages, which captures both the human impulse to brutalise, dominate, and destroy, and also the human imperative to push on in spite of it all, the need to believe in a better future.

Since then, Mo has self-published three novels: 1995’s Brownout On Breadfruit Boulevard; 1999’s Renegade or Halo2, and 2012’s Pure, all featuring protagonists caught between cultures and civilisations. Britain has been left behind – in an interview with the Guardian in 2000, Mo deemed it ‘antiseptic – a slow, safe, orderly society’. While his fierce independence might make him bristle against calls to revisit his works in the name of a contemporary ideal – of building a British-Chinese canon, or re-interrogating the empire – there was, to me, also an undeniable pleasure in following the stories themselves; on learning what they had to say about being fallible and human, and the brutalities and generosities we are capable of when we are pushed to the brink. The author may have left Britain behind, but his novels, read today, sound out a truth that the nation has long conveniently ignored to its own detriment. That violence, the hybridity of cultures, and the fluidity of national identity was always foundational in the making of Britain, too; denied for too long, the ghosts of history have their way of coming back.

The Redundancy of Courage by Timothy Mo

- By

- Timothy Mo

- Published by

- André Deutsch