The Booker Prize Podcast, Episode 7: Loitering with Intent by Muriel Spark

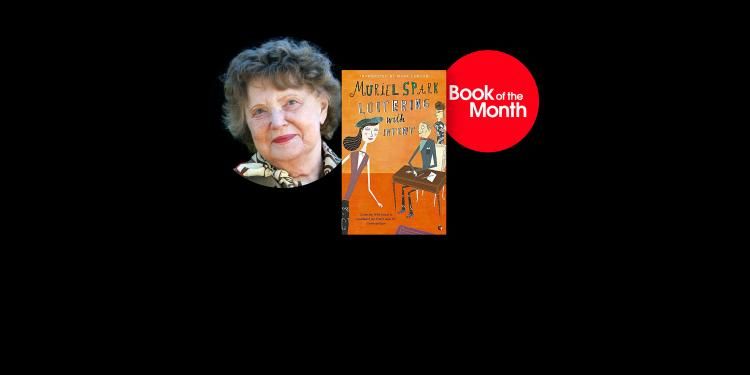

In this episode of The Booker Prize Podcast, our hosts – Jo Hamya and James Walton – discuss our August Book of the Month, which was shortlisted for the Booker Prize in 1981

Shortlisted for the Booker Prize in 1981, Loitering with Intent is an expertly crafted novel on art and artifice, one which delicately explores the ethical demands and constraints of authorship

Whether you’re new to Loitering with Intent or have read it and would like to explore it more deeply, here is our comprehensive guide.

A would-be novelist takes inspiration from life – but then finds the tables are mysteriously turned, in Muriel Spark’s entertaining literary joyride.

When Fleur Talbot takes up work for the snobbish Sir Quentin Oliver and the venal members of his Autobiographical Association, she is secretly delighted. Here is inspiration for her villain, Warrender Chase. But when Sir Quentin steals the finished manuscript for his own lunatic ends, life begins to imitate art with uncanny – and dangerous – predictability, for more than one of her characters has met an untimely end…

Loitering with Intent by Muriel Spark

Muriel Spark was born in Edinburgh on February 1, 1918. A poet and novelist, she also wrote children’s books, radio plays, a comedy and biographies.

She is best known for her stories and many successful novels, including Memento Mori, The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie, Loitering with Intent, The Comforters, A Far Cry from Kensington and The Public Image.

Over her long literary career, Muriel Spark won international praise and many awards, including the David Cohen British Literature Award, the T. S. Eliot Award, the Saltire Prize, the Boccaccio Prize for European Literature and the Italia Prize for dramatic radio.

She was shortlisted for the Booker Prize in 1969 and again in 1981 and her novel The Driver’s Seat was one of the novels shortlisted for the Lost Man Booker Prize 1970. She was also shortlisted, for her entire body of work, for the Man Booker International Prize 2005. She lived in London, New York, Zimbabwe, Rome and Tuscany, and died on April 13, 2006.

Muriel Spark, 2004

© Colin McPherson/Corbis via Getty ImagesFleur Talbot

Fleur Talbot is a young writer struggling to complete her first novel. Despite the obstacles standing in her way – she lives in a lacklustre bedsit renting from an awful landlord – she still rejoices at the wonders of being ‘an artist and a woman in the twentieth century’, with her life devoted to her craft. She spends her days observing those around her and storing up her findings for use in her writing and novels. She is marked by unreliability as a narrator, as the worlds of fiction and fact are continually blurred, and we are led to distrust Fleur’s version of events.

Sir Quentin Oliver

Sir Quentin Oliver is the director of the Autobiographical Association. He hires Fleur Talbot as his secretary and steals the finished manuscript of her novel Warrender Chase. He is described as a ‘psychological Jack the Ripper’, a pompous and self-serving man, suspected by Fleur and others to be taking advantage of the association’s clients for his own financial gain.

Sir Quentin Oliver hires Fleur Talbot as his secretary and steals the finished manuscript of her novel Warrender Chase

© CSA-Archive/Getty ImagesThe Guardian:

‘It is lyrical, joyous, formally close to perfect.’

The New York Times Book Review:

‘[Loitering with Intent,] robust and full-blooded, is a wise and mature work, and a brilliantly mischievous one. It is about a writer’s love affair with art – about a writer’s purpose and method, about the sources from which an artist draws inspiration. ”Words should convey ideas of truth and wonder,” says Fleur (whom we can be forgiven for thinking is Miss Spark’s alter ego); ”I see no reason to keep silent about my enjoyment of the sound of my own voice as I work.” Folly and weakness, guilt and sin, sadism and treachery, should be treated ”with a light and heartless hand. It seems to me a sort of hypocrisy for a writer to pretend to be undergoing tragic experiences when obviously one is sitting in relative comfort with a pen and paper.’

The Spectator:

‘So, as well as exploring the characters of 20 or so hilarious and cruelly-conceived people, we are made to think about the very nature of perception itself, the illusions which enable us to claim knowledge of other minds. We can only see the world in our own way unless we see it through the eyes of great art… Every word of Loitering with Intent, arcane, inconsequential and epigrammatic, could have been written by no one but Mrs Spark.’

The Sunday Times:

‘Loitering with Intent, like many of Muriel Spark’s novels, is about the art of fiction itself. To this extent it’s an important contribution to an understanding of her work and thought; a pity that it’s executed in a convoluted and over-literary way.’

The Times:

‘It has exuberant freshness. It is constantly inventive. It has wit and grace. It is intelligent. It shimmers with love. It is short.’

Times Literary Supplement:

‘It goes without saying that Loitering with Intent is beautifully written. It is also exciting, at times, and often very funny. Muriel Spark’s dry fluency used to be compared with Ivy Compton- Burnett’s; now it seems to resemble Beckett’s.’

The novel opens with a woman sitting in a Kensington graveyard when a policeman comes towards her. ‘I told him I was writing a poem and offered him a sandwich… He stopped to talk awhile, then he said good-bye…’ Why do you think Spark chose to begin the novel in a place that carries strong connotations of death and the afterlife? What meaning is there in this location?

Fleur’s job at the Autobiographical Association is to write the memoirs of eccentrics who patronise the organisation. These memoirs are then later stored for safekeeping. Fleur uses artist licence to make the members’ lives more exciting - adding in salacious details and embellishing stories. Why do you think Fleur chose to make these memoirs into works of fiction? How does this act connect to the larger themes of the novel?

Loitering with intent is presented to the reader as Fleur’s memoir, as she looks back ‘in the fullness of her years’ to the grim winter during the years 1949-1950, recounting the events that transpired. How does the biographical conceit affect your reading of the novel, especially when considering Fleur’s actions at the Autobiographical Association?

Loitering with Intent focuses on the unpredictability of artistic existence in mid-century London. Spark writes of debt collection letters and the cold bedsit room rented out by a swinish landlord, but within the novel is the refrain, ‘how wonderful it feels to be an artist and a woman in the twentieth century.’ What impression of being a woman and an artist at such a time does the novel leave you with?

Fleur is described as Catholic, but not the kind like her friend Dottie to be found ‘simpering about Our Lady.’ In a chapter of her novel, the villain Warrender Chase holds private prayer meetings in which he bullies his victims with the word of God. What are your thoughts on Spark’s representation of religion, and Catholicism in particular, throughout the novel?

Fleur can be described as an unreliable narrator and within the novel there are characters who cast aspersions on her sanity and mental health. As readers, we are left unsure as to whether she is transforming real life into fiction or if fiction has constructed reality. What effect does Fleur’s unreliability and the uncanny nature of the events in the novel have on your reading?

Fleur says in the novel that ‘words should convey ideas of truth and wonder?’ In what ways does the novel ruminate on the nature of truth? Would you say that Spark presents truth as related to the wondrous or the strange elements within the novel?

Spark incorporates two texts into the novel, John Henry Newman’s The English Theologian’s Apologia and Benvenuto Cellini’s Autobiography. What do you think this intertextuality adds to the novel?

Critics have described Loitering with Intent as a ‘wise and mature work.’ What wisdom do you think Spark wishes to impart on readers through her depiction of the travails of Fleur Talbot?

Writing in The Spectator, A.N Wilson said that the novel shows how ‘we can only see the world in our own way unless we see it through the eyes of great art’. Do you agree with Wilson’s statement? If so, how do you think the novel shows us the world in such a way?

Piccadilly Circus, London, 1949

© World History Archive/AlamyNational Library of Scotland: Muriel Spark and the Curious Work of Writing

The New Yorker: How Muriel Spark Came Home to Scotland

Lux: The 9 Lives of Muriel Spark

Lithub: On Muriel Spark’s Complicated Balancing of Writing and Motherhood

Scottish Review of Books: Muriel Spark: A Glance Through an Open Door

The Driver’s Seat by Muriel Spark

The Public Image by Muriel Spark

Travels with My Aunt by Graham Greene

Something to Answer For by P.H. Newby

Possession by A.S. Byatt

The Sea, The Sea by Iris Murdoch

The Driver’s Seat by Muriel Spark