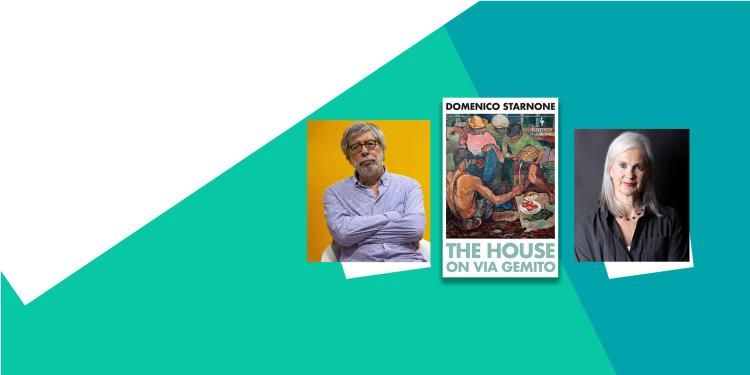

A Q&A with Domenico Starnone and Oonagh Stransky, author and translator of The House on Via Gemito

With The House on Via Gemito longlisted for the International Booker Prize 2024, we spoke to its author and translator about their experience of working on the novel together – and their favourite books

Read interviews with all of the longlisted authors and translators here.

Domenico Starnone

How does it feel to be longlisted for the International Booker Prize 2024, and what would winning the prize mean to you? Would it also have an impact on literature originating from Italy?

I’m happy of course. If a book translated from Italian won, it would be something new and perhaps it would lead to greater attention to a literature that is very lively and inventive.

What were the inspirations behind the book? What made you want to tell this particular story?

I wanted to tell the story of an unhappy artist and his family, against the backdrop of fascism and of post-war Italy. I took my father, a man of genius and great vitality, as a model. But, above all, I decided to write this story for love of my mother, to whom the book is dedicated.

How long did it take to write the book, and what does your writing process look like? Do you type or write in longhand? Are there multiple drafts? Is the plot and structure intricately mapped out in advance?

It took me a couple of years. But I had several unsatisfactory attempts behind me, and hundreds of pages of notes, memories, and testimonies. When I write, I don’t plan ahead. I start with notes in pencil, to which I subsequently give a provisional order. Then I move on to the first draft using the computer. I write many drafts before arriving to the final text.

What was the experience of working with the book’s translator, Oonagh Stransky, like? How closely did you work together on the English edition? Were there any surprising moments during your collaboration, or joyful moments, or challenges?

I admire the work of my translators, the texts are difficult especially due to the connection between language and dialect. Oonagh has great sensitivity and competence, and I have much respect for her. I always felt the book was in good hands. We wrote to each other when necessary.

What was your path to becoming a reader – what did you read as a child and what role did storytelling play in your younger years? Was there one book in particular that captured your imagination?

I am and have always been a reader who reads everything. I start from the assumption that even a bad book can have a page or even just two lines that will surprise me.

Domenico Starnone

© AlamyI considered novels a sort of preliminary training for a life that I promised myself would be full of adventures

— Domenico Starnone on how books influenced his life

Tell us about your reading habits. Which book or books are you reading at the moment, and why?

I’m reading Yanomami, l’esprit de la forêt by Bruce Albert and Davi Kopenawa. I started Molto molto tanto bene by Caterina Bonvicini. I just finished Il fuoco che ti porti dentro by Antonio Franchini. They are all books that, in very different ways, deal with the maternal image.

Tell us about a book that made you want to become a writer. How did this book inspire you to embark on your own creative journey, and how did it influence your writing style or aspirations as an author?

There were no books in my house. When I was a kid I’d borrow books from libraries, or buy them for a few pennies at the second-hand market. I didn’t have the money to buy new books. Up to the age of sixteen, I devoured nothing but nineteenth-century literature. I considered novels a sort of preliminary training for a life that I promised myself would be full of adventures. Then I too started feeling the impulse to write, so I started reading and rereading to understand how it was done. The first book that really struck me was The Trial by Franz Kafka, I read it when I was eighteen. From that moment on, everything I tried to write had a Kafkaesque feel. Then my Kafkaism faded, but I was left with an underlying tendency towards an ironically distorted realism.

Tell us about a book originally written in Italian that you would recommend to English readers. How has it left a lasting impression on you?

Libera nos a malo by Luigi Meneghello. It dates back to 1963, and it was important for me, it encouraged me to work on the relationship between language and dialect. It was translated into English by Frederika Randall with the title Deliver Us.

Do you have a favourite International Booker Prize-winning or shortlisted novel and, if so, why?

There are several. One I particularly loved is The Impostor by Javier Cercas, translated by Frank Wynne.

What role do you think translated fiction plays in promoting a more inclusive and diverse literary canon, and how can we encourage more people to read it?

Having one’s work translated is an important step, especially if you write in a language that’s read only in your country. But being translated is not enough, the book must find readers. An important prize, which focuses on the fundamental role of translators, can be of great help.

Oonagh Stransky

How does it feel to be longlisted for the International Booker Prize 2024 – an award which recognises authors and translators equally – and what would winning the prize mean to you?

The first reaction I had to the announcement was of lightness, with the announcement lifting many of the burdens that come with this profession. Then I felt seen and recognised for my hard work, as if it’s all been worth it. Finally, I found myself smiling broadly – so I was right about how good this book is!

Arriving at this stage is already a big deal for me; winning the prize would confirm the power of persistence. Translating literature for a living is not an easy path, but I’ve stuck with it and there have been some fantastic moments, such as this one. Winning the prize would also underscore Domenico Starnone’s incredible talent.

How long did it take to translate the book, and what does your working process look like? Do you read the book multiple times first? Do you translate it in the order it’s written?

When translating contemporary literature, I never read the whole book first. I need to be aware of the feelings I experience while I’m reading it for the first time and make sure that those emotions are present in the translation. I need to feel all the tension, humour, violence, anguish, desire, confusion…. I then go through many editing phases, always with the original by my side.

Translating Via Gemito took me eight months, working seven hours a day, six or seven days a week. I researched words and phrases in dialect by using online resources or querying friends. I kept a running list of notes: things that surprised me, doubts, and tangentially related ideas. Before handing in any manuscript, I always read it out loud. Working with the editor on the text and seeing the book laid out in “proof” form are two additional key moments in the process.

Aside from the book, what other writing did you draw inspiration from for your translation?

When translating contemporary literature, I don’t draw on other writings but focus solely on the narrative voice (unless the book is a ‘written in the vein of…’ genre, like a literary gamebook I once translated). I allow myself to be drawn in; I let myself make connections with my own experiences. In the case of Via Gemito, I reflected at length on intense memories of homes I’ve lived in, spaces, and rooms. I’ve been to Naples, but even so, I pored over maps of the city, tracing streets with my finger, searching with the narrator for something firm to grasp onto. I understand what it means to be the child of an artist because my own mother was a painter: I could smell the studio space, visualise the tools, I know how an artist concentrates, and their total, intense devotion to their work. By making these kinds of personal connections, I was better able to carry over Starnone’s story into English.

What was your path to becoming a reader – what did you read as a child and what role did storytelling play in your younger years? Was there one book in particular that captured your imagination?

I read everything I could get my hands on. Our house was filled with books, but I loved reading certain sections of The Herald Tribune, comic books, and the National Geographic magazine. As a very young reader, I had a series of classic fairy tales with gorgeous illustrations that were very large; I remember holding them in my small hands and trying to read. A few years later, I loved Ripley’s Believe it or Not, Arthur Gross’ Children’s Garden of Bible Stories, and nature encyclopedias. Then, all the classics: Harriet the Spy, the Mouse and the Motorcycle, The Great Brain, Trumpet of the Swan, Nancy Drew books, Judy Blume, Roald Dahl. I was a bit of a rowdy kid in middle school and often had to stay after school as punishment. More often than not, I was sent to the library to help straighten up books and wrap them in plastic covers. It was fun!

Oonagh Stransky

Tell us about your path to becoming a translator. Were there any books that inspired you to embark on this career?

As a child, I grew up hearing multiple languages both at home and beyond, and being a curious kid, I always tried to figure out what people were saying… I only started studying Italian, though, in college, where I initially wanted to study Book Arts but then majored in Comparative Literature. I got a sound base in the language at Middlebury College summer school, took language and literature classes at UC Berkeley, and learned even more at the Università di Firenze, when I studied abroad for a year. Italian became much more than an academic pursuit only after graduation, when I moved there, married an Italian, and started a family. My acquisition of the language was facilitated by the fact that my husband didn’t speak English, his parents were educators, and we lived in a remote area where there weren’t many other English speakers. Thanks to living where I did, when I did, and with the people I did, Italian became a natural form of expression.

Flash forward a dozen years: I’m living in New York City, I’m divorced, I’ve just left a good but dull job at the Italian Consulate General, and I’m taking creative writing classes at Columbia. I decide to take the leap, and unite my love of reading, writing, books, and languages with a profession. I try my hand at translating Antonio Tabucchi’s novella about Fernando Pessoa, which leads me to my first contract with City Lights for a noir by Carlo Lucarelli. I start to pursue a Master’s in Italian at Columbia University and find myself dreaming of translating Montale’s collection of short stories, something that comes true only twenty years later…

I feel compelled to point out that I have not always been a full-time literary translator but have held many different jobs over the years. I was a high school English teacher in New York City for five years, I taught English here in Italy, I worked in the wine industry in Montepulciano for four years, and I’ve done my share of commercial translations: travel guides, cookery books, hotel websites, books about plants, art, and so on. Although I was encouraged to teach at the university level, I never wanted to be a professor. I consider translation more of an art, and I don’t like overintellectualizing it.

What are your reading habits under normal circumstances? Which book or books are you reading at the moment, and why?

While working on a translation, I like to stay focused on that text and don’t want anything to interrupt me from hearing the voices that come from the book. Right now, though, before I dive into a new translation, I’m enjoying several books. I recently finished Demon Copperhead by Barbara Kingsolver and Loved and Missed by Susie Boyt, and I’m currently reading Splinters by Leslie Jamison.

Tell us about a book originally written in Italian you would recommend to English readers. How has it left a lasting impression on you?

Marcovaldo, by Italo Calvino, was the first book I read in Italian, looking up words in the dictionary and making notes in the margins as I went… I will always remember the main character: his simple but determined way, the way he tried to experience the gifts of nature in a city that just kept getting louder, faster, brighter… I remember being amazed at Calvino’s nimble storytelling, and I was proud of myself for understanding it.

Marcovaldo by Italo Calvino

Translated fiction brings readers to new worlds where certain aspects of life – cultural practices, habits, histories, social matters – are different but where other issues – feelings and situations – are shared

Which work of translated fiction do you wish you had translated yourself, and what aspects of this particular work do you admire most?

I deeply admired Kenneth Steven’s translation of The Half Brother by Lars Saabye Christensen. I was captivated by the story, and the translator made it feel so natural, making it a compelling read.

Czech literature has a special place in my heart because my father was born in Prague, and I always heard the language spoken at home. I admire Michael Henry Heim’s translation of Kundera’s The Unbearable Lightness of Being and enjoyed Bringing up Girls in Bohemia, by Michal Viewegh, translated by A.G. Brain.

Do you have a favourite International Booker Prize-winning or shortlisted novel and, if so, why?

I was curious to read last year’s winner, Time Shelter, by Georgi Gospodinov, translated by Angela Rodel, because of my interest in the power of memory and remembering. I found the descriptions of time to be incredibly striking, I thought the premise was original and quirky; everything feels dreamlike but, at the same time, necessary – a kind of fanta-philosophy.

What role do you think translated fiction plays in promoting a more inclusive and diverse literary canon, and how can we encourage more people to read it?

Translated fiction brings readers to new worlds where certain aspects of life – cultural practices, habits, histories, social matters – are different but where other issues – feelings and situations – are shared. By discovering our commonalities, readers inevitably become more tolerant and empathetic.

I’d like to see the topic of translation discussed more in schools. When young people try to do their own short translations, they appreciate how difficult it is to write well in English and how empowering it is to know another language. Such activities might encourage young people to read more widely.

Time Shelter by Georgi Gospodinov translated by Angela Rodel, winner of the International Booker Prize 2023

- By

- Domenico Starnone

- Translated by

- Oonagh Stransky

- Published by

- Europa Editions