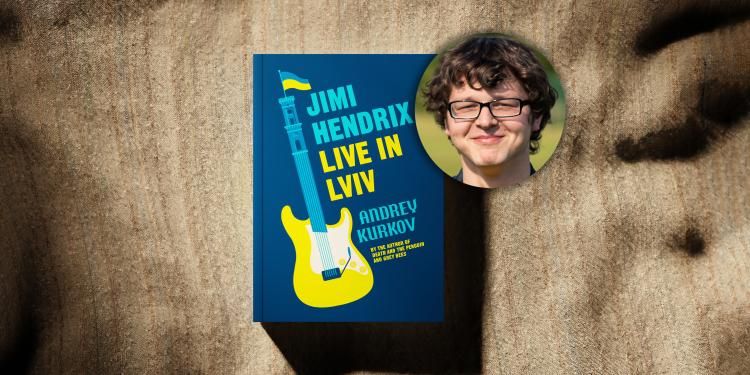

Andrey Kurkov interview: ‘I remember thinking that I owed Lviv a novel’

Longlisted for the International Booker Prize 2023, author Andrey Kurkov talks about Jimi Hendrix Live in Lviv in an exclusive interview

With Jimi Hendrix Live in Lviv longlisted for the International Booker Prize 2023, its translator talks about working on the book alongside his Master’s degree and immersing himself in the book’s Ukrainian setting

Read interviews with all of the longlisted authors and translators here.

How does it feel to be longlisted for the International Booker Prize 2023 – an award which recognises the art of translation in such a way that the translators and author share the prize money equally should they win - and what would winning the prize mean to you?

Hendrix… is my first published translation. To be honest with you, being longlisted for the International Booker is such surreally good news that I worry it’ll set my hopes too high for the books that follow! I joke, but it’s a truly wonderful honour. I’m still coming to terms with seeing my own name next to Andrey’s in the book itself, so to have such a vote of confidence from the judges’ panel before we even reach publication day is a great feeling. I think if I started thinking about winning the prize and what that would mean for me now it would probably drive me crazy – if being on this longlist is the most significant accolade I ever receive, I will retire a contented translator. But it would of course be incredible to be considered for the top prize.

How long did it take to translate the book, and what does your working process look like? Do you read the book multiple times first? Do you translate it in the order it’s written?

This book was a fairly fast turnaround – when Paul Engles, my editor at Maclehose, asked me when I would likely be handing in the first version of the full manuscript, I was starting a Master’s degree in just over five months. So that became my deadline! I squeezed editing in between terms and replied to proofreaders’ comments between seminars. It’s been a busy year.

I did not read the book multiple times first. In fact, I read it as I was doing my first draft, then went back over it and corrected anything that knowledge of the later parts changed about the beginning. I was very influenced in my day-to-day translation work and process by Danny Hahn’s translation diary, which was eventually published in book form as Catching Fire (Charco Press, 2022). Like Danny, I rush to the end of a first draft, and then go back over that draft several times, ironing out kinks, resolving highlighted ‘problem’ passages, hewing and shaving until I can bear to let other people see it.

What was the experience of working with Andrey Kurkov like? How closely did you work together? Was it a very collaborative process? Were there any surprising moments during your collaboration, or joyful moments, or challenges?

Andrey is, understandably, a very busy man at the moment. We exchanged a few emails, largely introducing ourselves to one another rather than discussing the translation in any detail. I largely tried to resolve translation questions myself or with friends and colleagues, although there were some frantic last-minute questions about editions and versions that Andrey was able to provide some clarity on. On a couple of questions, I turned to friends more versed in Polish and/or Ukrainian than myself. I had a couple of very helpful discussions with fellow Kurkov translator Boris Dralyuk - always a pleasure to talk to and a fount of wisdom on anything to do with translation. When it comes to finding the right word, or remembering what things are called in English, whoever is in the room or next door becomes a point of contact – that usually means my parents or sister, my partner Camila, or anyone I’m sat with in a coffee shop or library.

Reuben Woolley

I squeezed editing in between [university] terms and replied to proofreaders’ comments between seminars. It’s been a busy year

Aside from the book, what other writing did you draw inspiration from for your translation?

Hendrix… is a novel about the city and people of Lviv, a place with a fascinating and complex history, and streets full of the sediment of rising and falling empires. To acquaint myself with some of that sediment, Philippe Sands’ East-West Street is a brilliant and innovative book about the city and the experience of the 20th century across central and eastern Europe more broadly. I also found Serhii Plokhy’s work on Ukrainian history engaging and dependable. Finally, the late, great historian and activist Marko Bojcun, with whom I was privileged to work in the Ukraine Solidarity Campaign here in the UK, wrote brilliantly on Ukrainian history and politics, including a collection of essays on modern Ukrainian political economy and a historical academic work on the workers’ movement at the time of the revolution. Marko passed away very recently; he will be deeply missed, and his work deserves to be read widely.

What was your path to becoming a translator of literary fiction? What would you say to someone who is considering such a career for themselves?

My path into translation was one of constantly making friends with translators and showing them my work, discussing and getting advice, going away to edit, then discussing some more, until finally someone told me to pull the trigger and get in touch with an author. I was helped in that process in no small way by one of my tutors at university, Oliver Ready, who is himself an excellent translator of Russian literature. Oliver gave me some very important early pointers on where to go and who to introduce myself to. I was also extremely lucky to be mentored, first informally, then formally through the National Centre for Writing’s Emerging Translator Mentorship, by the translator Robert Chandler. Robert took me under his wing and encouraged me to submit my work to publishers and editors – without him I would never have had the confidence to put myself out into the world and call myself a translator.

My advice to anyone who’s interested would be that translation is a profession that necessarily starts as a hobby. If you’re at all interested, go and find things that intrigue you, things that you think the world needs to read, or hear, or see, and just try your hand. Get used to showing your work to others; get used to reaching out to authors that you’d like to work with; get used to reaching out to other translators (we’re a friendly bunch!); get used to receiving criticism of your work and learning to use it to your advantage; get used to calling yourself a translator, because eventually you might reach a stage where you would like to try and publish something, and you will have to project your translation to others as a profession, when it might still feel like a hobby.

Why do you feel it’s important for us to celebrate translated fiction?

Because the world is far too interesting a place for us to only care about what happens in its Anglophone regions.

If you had to choose three works of fiction that have inspired your career the most, what would they be and why?

The first one is a cheat: The Gospel According To… by Sergey Khazov-Cassia, translated by me, forthcoming from Polari Press. Very much the project that propelled me into literary translation, and working closely with Sergey and any number of others on it has been an incredible journey that has taken me from a witless undergraduate student to a witless professional translator.

Crime and Punishment, in the Penguin edition translated by Oliver Ready. Oliver’s translation, apart from being the best out there, was the book I read at the age of 17 as I was looking to apply to study Russian literature at university. My enduring obsession (‘love’ wouldn’t be the term, I don’t think) with that book and its writer dragged me firmly into the academic world of literary studies, as well as its translator eventually showing me the way into that world, too.

Finally, Grey Bees by Andrey Kurkov, translated by Boris Dralyuk. The first of Andrey’s books that I read, in a wonderful translation that I was very glad to see win the inaugural National Book Critics Circle translation prize in America recently. The book itself is a vitally important one to understand the second half of the 2010s in Ukraine, and the layers of complexity to the cultural and political questions at play in the current war. Boris’ painstaking and meticulous approach to all of his translations makes the ease and lightness of the prose he produces all the more impressive; it was a style I found hugely useful as a reference point when coming to my own translation of Andrey’s work.

Andrey Kurkov