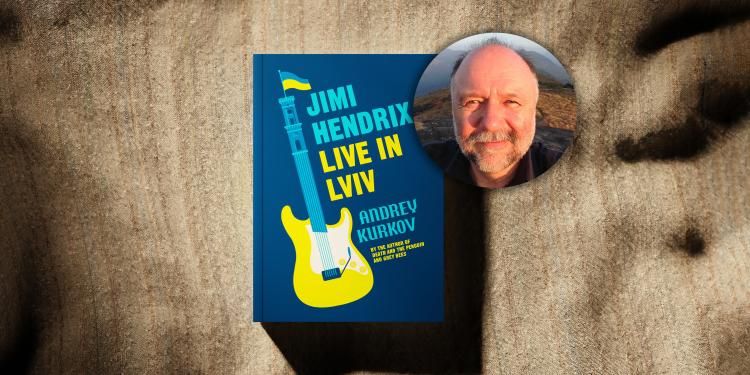

Reuben Woolley interview: ‘Translation is a profession that necessarily starts as a hobby’

Longlisted for the International Booker Prize 2023, translator Reuben Woolley talks about Jimi Hendrix Live in Lviv in an exclusive interview

With Jimi Hendrix Live in Lviv longlisted for the International Booker Prize 2023, its author talks about why literature has to travel – and why a good translation is truly a work of art

Read interviews with all of the longlisted authors and translators here.

How does it feel to be longlisted for the International Booker Prize 2023, and what would winning mean to you?

I am greatly moved to think that this novel – born out of my love for the Ukrainian city of Lviv – has resonated with the International Booker Prize jury. It seems to me now that I wrote Jimi Hendrix Live in Lviv in another life. The jury’s recognition confirms for me the value the city’s essential qualities and suggests that the messy struggles of post-Soviet life remain relevant and of interest to the English language reader. Winning would maximize that interest and further focus literary attention on Ukraine and Ukraine’s recent history. It would also mean a great deal to the city of Lviv and its inhabitants.

What were the inspirations behind the book? What made you want to tell this particular story?

The city of Lviv - its special character – has always fascinated me. I remember Soviet Lviv – grey, rainy and with an aroma of coffee in the streets. Later, in the post-Soviet years, Lviv quickly restored its Bohemian/intellectual image. I remember thinking that I owed Lviv a novel. It took almost two years of monthly trips there. Half of the characters in the novel are real people who appear under their real names. They have become my very good friends since then.

How long did it take to write the book, and what does your writing process look like? Do you type or write in longhand? Are there multiple drafts or sudden bursts of activity? Is the plot and structure intricately mapped out in advance?

It took a bit more than two years. The first year was all about walking the streets of Lviv and talking to people, listening to them, and asking questions about life in Lviv in the 1970s and 1980s. I don’t write plans for my novels. Usually, I develop the story in my imagination and tell friends episodes in different variations, checking their reactions. Once the story is formed in my head, I start writing it down, but while I write, I make more changes - some minor, some very important. I use a laptop to write, but I carry a notebook around with me all the time for urgent messages to myself.

Where do you write? What does your working space look like?

Much of the writing for Jimi Hendrix Live in Lviv was done in my village house, not far from Kyiv. I have a little room there that looks out onto my neighbour’s beautifully kept garden, but some pages were created on the express trains Kyiv-Lviv, Lviv-Kyiv.

Andrey Kurkov

© GL Portrait/AlamyHalf of the characters in the novel are real people who appear under their real names. They have become my very good friends

What was the experience of working with the book’s translator, Reuben Woolley, like? How closely did you work together on the English edition? Did you offer any specific guidance or advice? Were there any surprising moments during your collaboration, or joyful moments, or challenges?

Reuben and I exchanged emails, and I was always happy to get his messages and suggestions. Once he wrote to say that the first thing he would do when the war in Ukraine was over would be to visit Lviv. The novel made him very curious about the city and Ukraine in general. I was particularly touched by his interest in the work and life of Lesia Sanotska – a real person, who organized the first-ever shelter for homeless people in Lviv. She passed away from cancer three years after the novel was published. In a way, this novel is also a small tribute to her.

Why do you feel it’s important for us to celebrate translated fiction?

Literature has to travel, and readers have to move out of their ‘home zone’ to greet some literary guests at their port of entry – the translation. These journeys result in enrichment for all concerned. Celebrating translated fiction promotes and supports these journeys.

I feel that translators need all the attention they can get. A good translation is truly a work of art in which the translator inevitably creates channels by which a different culture can be understood and appreciated.

If you had to choose three works of fiction that have inspired your career the most, what would they be and why?

Early on, there was The Castle by Franz Kafka, who continues to fascinate me. He had a rare gift for creating a fantastic but, at the same time, very believable world and populating it with heroes who were suffering from that world.

The novel Hunger by Knut Hamsun showed me how powerful psychological prose can be. It was also because of Knut Hamsun that I began to read and then write books while listening to classical music.

For the past few years, East-West Street by Philip Sands has regularly returned to my mind. This non-fiction book pushed me to a deeper study of recent history and led me to the conviction that non-fiction can be even stronger than fiction. What has struck me most is that the heroes in such prose - real historical figures - remain with the reader much longer than fictional characters.

Reuben Woolley