Everything you need to know about the Booker Prize 2023 shortlist

As the Booker Prize 2023 shortlist is announced, we’ve pulled together the most interesting facts and trends that have emerged in this year’s selection

In her tender and moving debut novel, Chetna Maroo captures grief, sisterhood and a teenage girl’s struggle to transcend herself

Whether you’re new to the book or have read it and would like to explore it more deeply, here is our comprehensive guide, featuring insights from critics, our judges and the book’s author, as well as discussion points and suggestions for further reading.

Eleven-year-old Gopi has been playing squash since she was old enough to hold a racket. When her mother dies, her father enlists her in a quietly brutal training regimen, and the game becomes her world.

Slowly, she grows apart from her sisters. Her life is reduced to the sport, guided by its rhythms: the serve, the volley, the drive, the shot and its echo. But on the court, she is not alone. She is with her pa. She is with Ged, a 13-year-old boy with his own formidable talent. She is with the players who have come before her. She is in awe.

Gopi

Gopi is the narrator of Western Lane. She is 11, and the youngest of three siblings, all girls. Gopi is shy and lives in the shadows of the family. She is incredibly close to her sisters, and often mirrors her sister, Khush, out of adoration. Gopi is a natural and talented squash player, and with the mentorship of her father, begins to succeed at the game.

Khush

Khush is the middle sister of the family, aged 13. She is a thinker and a storyteller of the family, ‘she remembered things we didn’t think of’, said Gopi. Khush is reserved in her grief for her mother, and still speaks to her in Gujarati at nightfall, even after her death.

Mona

Mona is the eldest sister at 15. She is very concerned with external appearances and how the family are perceived by those around them. Mona is practical and feels duty-bound, after her mother’s death, to step into her shoes and care for the family.

Pa

Pa is a quiet man, and is bereft when his wife dies. He struggles to be able to articulate his grief, and communicate with his children. Squash, the game they have all played as a family since the children were tiny, becomes a coping mechanism for him, and gives him purpose.

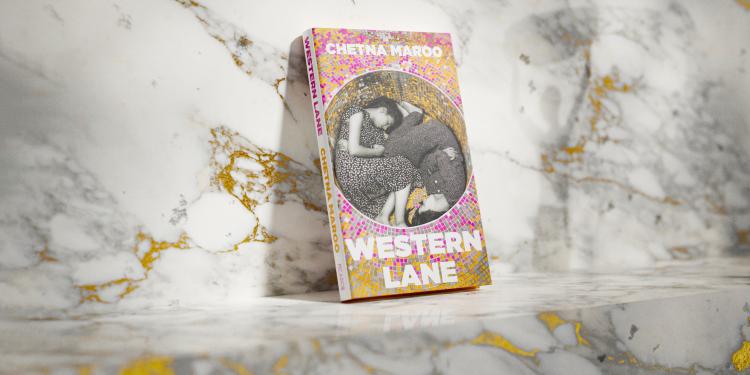

Western Lane by Chetna Maroo

Chetna Maroo was born in Kenya and lives in London. Her stories have appeared in anthologies and have been published in the Paris Review, the Stinging Fly and the Dublin Review.

She was the recipient of the 2022 Plimpton Prize for Fiction, awarded annually since 1993 by the Paris Review to celebrate an outstanding piece of fiction by an emerging writer published in the magazine during the preceding year. Before becoming a full-time writer, she worked as an accountant. Western Lane, which is shorlisted for the Booker Prize 2023, is her first novel.

Chetna Maroo

‘Western Lane is a mesmerising novel about how silence can reverberate within a family in the aftermath of grief. The story unfolds on a squash court; the reader quickly learns how sport can act as a balm for the living. It is also about sisterhood, and about the love that remains after a devastating loss. The language in this novel is truly something to be savoured. Western Lane contains crystalline prose that also feels warm and tender, which can be a difficult balance to strike.’

Booker Prize judges 2023: (clockwise from top right) Mary Jean Chan, James Shapiro, Esi Edugyan, Robert Webb and Adjoa Andoh

© David Parry/Booker Prize FoundationKirkus Reviews

‘Maroo’s subtle and elegant writing at first seems surprisingly restrained for a novel about a subject as high-spirited and energetic as squash and from a narrator as generally high-spirited and energetic as an 11-year-old girl. But Gopi’s retrospective narration accumulates slow layers of heartbreak as the story proceeds, patiently building up an entire landscape of emotion through gestures, silences, and overheard murmurings in the dark. A debut novel of immense poise and promise.’

Saachi Gupti, Vogue India

‘Western Lane has been appreciated for remarkably connecting the emotional world to the physical with dynamic and sharp descriptions like the sound “of a ball hit clean and hard… with a close echo.” Tenderly exploring themes of loss, sisterhood and adolescence through the sport of squash, the book tells a captivating coming-of-age story that shines a light on the complexities of grief and the simple beauty that lies within the ordinary.’

Ivy Pochoda, New York Times

‘The beauty of Maroo’s novel lies in that unfolding, the narrative shaped as much by what is on the page as by what’s left unsaid. In the aftermath of their mother’s death, a strangulated silence envelops the house Gopi shares with her older sisters, Mona and Khush. They struggle to manage their grief under the suspicious gaze of their close-knit Gujarati community, with no help from their distant and distracted father. Conversations are dropped before they start. Language is hampered by stammers and cultural barricades as well as by things too scary and distressing to sound out.’

Claire Allfree, The Times

‘It sounds obvious, doesn’t it? Open a novel with a dead mother, then have a daughter left behind find a compensatory solace in the rigour and beauty of sport. Yet like the space inhabited by that missing ball, this quiet, elegantly compressed coming-of-age novel, just 160 pages long, operates most powerfully in the gaps outside the plot. What’s more, Chetna Maroo defies the memo when it comes to what novels about immigrant families ought to do.’

Danny Denton, The Irish Times

‘In the act of making books, writers make choices on every line, with every word. This is a debut in which Chetna Maroo gets every choice right, even the riskier ones. It reminds me of Kazuo Ishiguro’s debut (A Pale View of Hills) in that sense, and it has the same quality of being so calm, so confident, so close to the profound and yet rooted in real experience. Think also Marilynne Robinson, and Ocean Vuong (at his very best). The writing is beautiful and wise; the feeling both hauntological and deeply human.’

Tenderly exploring themes of loss, sisterhood and adolescence through the sport of squash, the book tells a captivating coming-of-age story that shines a light on the complexities of grief and the simple beauty that lies within the ordinary

‘Squash was simply where the story began for me. It started with the feeling of being inside a squash court, with a voice saying, ‘There were three of us.’ I knew there were three sisters in the court. I knew there was a father on the balcony above, instructing the girls. And I knew they all felt the presence of an absent mother. It’s unusual for me to experience such a clear starting impulse for a story. Though I played squash for many years and the game is still vivid in my imagination I don’t know where the connection with this grieving family came from, but I trusted it.

As I began writing, it made sense to me – the way attention is focused outwards in the game, the concentration, the movement of bodies in sync with one another. There was also something about the squash court itself, about the simple white box: it’s such a surreal, unfamiliar place, and in part because of the unfamiliarity it’s a place where time seems suspended and the outside world can be forgotten.’

Read Chetna Maroo’s full interview here.

Chetna Maroo

© Graeme JacksonThe story is told from the first-person perspective of Gopi, the youngest of three daughters in a family dealing with the loss of their mother. Gopi’s narration is sparse, befitting a storyteller who is coming of age. Why do you think the author chose to tell the story from the perspective of an 11-year-old child - and how does it benefit the novel?

Western Lane is set in the 1980s London suburbs, where Gopi and her family are British-Indian immigrants. How insightful a portrayal did you find the depiction of immigration? What cultural struggles do you think they faced during this time?

After the death of the family’s mother, the children and Pa channel their grief, unusually, into squash. What is it about this sport, and the act of this game in particular that allows them to process their mother’s death? Without this, how might they have dealt with the tragedy?

‘The effort to speak made him wince,’ says Gopi at one point, of her Pa. (Page 97). The book adheres to a show, don’t tell, philosophy, with much of the novel concerned with what resides in the silent spaces. Discuss how the prose, and the unsaid, serve the story, and whether you found it affecting.

‘She began to manage everything in the house, but she sought Pa’s opinions on things and listened to what he said. […] She was attentive to us, even kind. Sometimes we could feel the strain in her, the mental and physical burden of being something she was not.’ (Page 69). Eldest sister, Mona, begins to adopt a maternal role after their mother’s death. Discuss the consequences of this for her - is it fair to say she is fulfilling a cultural expectation? Is she a victim of patriarchy - or both?

Though not explicit, the author alludes to darker experiences within the girl’s everyday lives. ‘It was amazing to us that none of the children nearby went in there. We were the only ones. No one spat on us from a height or told us to go home. No one ran us out of there. No one came near.’ (Page 20). ‘In front of the open section of the fort was a grass-covered hill as tall as our house […] Opposite, the main road with the bus stop and the underpass we avoided.’ (Page 21). Discuss these statements and other sentiments in the book, with regards to racism and anti-immigration rhetoric in the U.K.

‘Pa ran a thumb around the silver frame. After a long time, he put my racket on the table between us. ‘It is very nice,’ he said. ‘You did well.’ He said this, but with his eyes and his body – his shoulders, his throat, the white bones visible under his skin – he was telling us that in one day we had exposed him, left him behind, left him wide open to whatever was coming for Him.’ (Page 76). In this passage, Gopi and her sisters have travelled to London to buy a new squash racquet. What is the subtext here - why has this simple purchase left Pa ‘exposed’?

‘We heard Susilaben whisper in the hallway, ‘Does Ranjan know?’ She was talking about Ged’s mother. ‘Know what, Auntie?’ Mona said, and Susilaben made a jumbled reply and left.’ (Page 8). After their mother’s death, the Gujarati community around the family become watchful. They provide instruction for the family, which is often unwanted. What cultural expectations are the family balancing, and perhaps, disregarding?

‘The book culminates in the squash tournament Gopi has been working toward through the novel. Discuss Gopi’s journey as a player. How invested in the sport was she personally, versus how much of it was her father’s drive?

‘I knew he was going to tell me it was up to me, and I knew that if I said yes, then we would be close again. But I was already answering him.’ (Page 120). Gopi’s father suggests she moves to Edinburgh to live with her aunt and uncle, to which Mona agrees. To what extent do you think she was happy to go?

Small Things Like These by Claire Keegan

Pearl by Siân Hughes

A Monster Calls by Patrick Ness

On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous by Ocean Voung