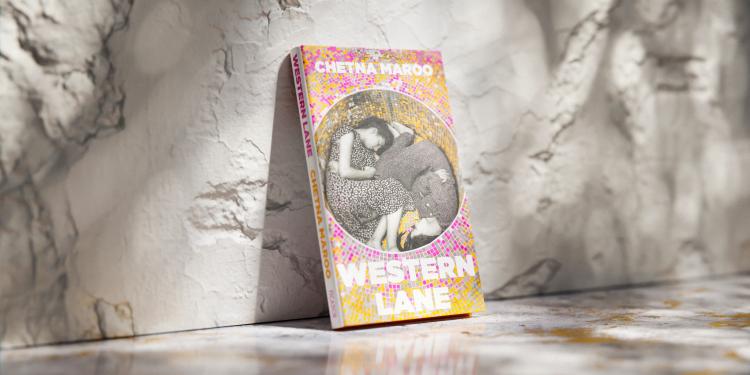

Reading list

Chetna Maroo’s tender and moving debut novel about grief, sisterhood, a teenage girl’s struggle to transcend herself – and squash

Eleven-year-old Gopi has been playing squash since she was old enough to hold a racket. When her mother dies, her father enlists her in a quietly brutal training regimen, and the game becomes her world.

Slowly, she grows apart from her sisters. Her life is reduced to the sport, guided by its rhythms: the serve, the volley, the drive, the shot and its echo. But on the court, she is not alone. She is with her pa. She is with Ged, a 13-year-old boy with his own formidable talent. She is with the players who have come before her. She is in awe.

I don’t know if you have ever stood in the middle of a squash court – on the T – and listened to what is going on next door. What I’m thinking of is the sound from the next court of a ball hit clean and hard. It’s a quick, low pistol-shot of a sound, with a close echo. The echo, which is the ball striking the wall of the court, is louder than the shot itself. This is what I hear when I remember the year after our mother died, and our father had us practising at Western Lane two, three, four hours a day. It must have been an evening session after school, the first time I noticed it. My legs were so tired I didn’t know if I could keep going and I was just standing on the T with my racket head down, looking at the side wall that was smudged with the washed-out marks from all the balls that had skimmed its surface. I was supposed to serve, and my father would return with a drive and I would volley, and my father would drive, and I would volley, aiming always for the red service line on the front wall. My father was standing far back, waiting. I knew from his silence that he wasn’t going to move first, and all I could do was serve and volley or disappoint him. The smudges on the wall blurred one into the other and I thought that surely I would fall. That was when it started up. A steady, melancholy rhythm from the other court, the shot and its echo, over and over again, like some sort of deliverance. I could tell it was one person conducting a drill. And I knew who it was. I stood there, listening, and the sound poured into me, into my nerves and bones, and it was with a feeling of having been rescued that I raised my racket and served.

There were three of us, all girls. When Ma died, I was eleven, Khush was thirteen, Mona fifteen. We’d been playing squash and badminton twice a week ever since we were old enough to hold a racket, but it was nothing like the regime that came after. Mona said that all of it, the sprints and the ghosting and the three-hour drills, started when our aunt Ranjan told Pa that what we girls needed was exercise and discipline and Pa sat quiet and let her tell him what to do.

That was at the beginning of autumn. The weather had turned from unseasonably dry and warm to humid. The air was oppressive and the streets smelled of decomposing food.

In this heat, a number of days after Ma’s funeral, we had driven four hundred miles to Edinburgh to have a meal at our aunt’s home to mark the end of our mourning period, and Aunt Ranjan told Pa we were wild.

Chetna Maroo

© Graeme JacksonIt wasn’t yet midday and it was already too warm for Uncle Pavan. His face was glowing and pink as anything. He put a hand on the table, tapped his four fingers on the cloth, all at once, and then moved his hand to his thigh. He needed a smoke

We were right there in her kitchen with her and Pa when she said it. Mona was washing potatoes in the sink. Her head was bowed and her sleeves were pushed to her elbows because she wasn’t just rinsing the mud away. She was really scrubbing. Her ponytail swung over one shoulder. Khush was peeling slowly, staring out of the window. I was at the table seeding pomegranates. Aunt Ranjan had scolded Khush for wearing her hair loose in the kitchen, and then she’d turned to me and pulled up half of the white cloth and put newspapers down so I wouldn’t get juice on her new dining set. It was a beautiful set, waxed and dark.

From where I was sitting I could see the gulab jamun Aunt Ranjan had prepared early that same morning. The dark-golden balls of sponge were already soaked in sugar syrup and piled generously in a glass bowl at the end of the counter.

Aunt Ranjan saw me looking.

‘Gopi,’ she said.

I froze in place, blushing fiercely at the sound of my name.

Aunt Ranjan stood up. She positioned herself so that she blocked my view of the sweets. I didn’t know why but it seemed important to me that I not shift my focus, that I make it seem as if I’d been looking at nothing all along.

‘Wild,’ Aunt Ranjan said a second time, her eyes still on me. ‘And it is no secret.’

Then she turned to Pa, and it was true that he just sat there looking at nothing, saying nothing.

Aunt Ranjan waited.

‘Well, I have said my piece,’ she said at last. ‘Now it is up to you.’

Pa raised his eyes to look at Aunt Ranjan for a moment, and there was a coolness in them that we were used to but Aunt Ranjan was not. Her cheeks reddened. The pressure cooker on the gas ring gave a thin, high whistle and the kitchen was suddenly warm with steam and the smell of overcooked lentils. Aunt Ranjan dabbed her forehead with a clean tea towel off the back of a chair.

‘I told Charu,’ she said. ‘I am not blaming her, brother, but I am telling you it is not too late for your girls.’

It was quiet. And then my sister Mona crossed to the worktop, removed the pressure cooker from the ring, and banged it hard onto the granite counter. The bowl of gulab jamun at the far end juddered and Mona stood with her potato-muddied hands on the lid of Aunt Ranjan’s pressure cooker, staring at Pa.

Aunt Ranjan turned off the taps that Mona had left running and went to her.

‘Not like that, child,’ she said to Mona.

Our uncle came in then, as if wandering into someone else’s kitchen. Maybe he would have gone right through into his garden but he looked at Mona, then Pa, and stood in the middle of the floor for a few seconds before approaching the table and sitting down between Pa and me. We liked Uncle Pavan. He was Pa’s younger brother and he was big and kind and enjoyed smoking outside and thinking about the past.

Uncle Pavan was forty. Pa was almost forty-five. But everyone talked about how handsome the brothers had become as if they had only lately grown into adulthood. After Ma died, our aunties’ eyes followed Pa from the dinner table to the sink or out into the garden. They were sorry for him, but they were also trying to get the measure of something and we knew it had to do with the space that had opened out in front of him.

It wasn’t yet midday and it was already too warm for Uncle Pavan. His face was glowing and pink as anything. He put a hand on the table, tapped his four fingers on the cloth, all at once, and then moved his hand to his thigh. He needed a smoke. He glanced at Pa and clasped his hands in his lap, ready to talk. Khush had poured Uncle Pavan a glass of water, and seeing he was ready she placed it on the table in front of him and sat down to hear what he had to say. Uncle Pavan gave her a grateful look and began.

‘It was the middle of a heat wave,’ he said. He leaned towards Pa. ‘Do you remember? The night you told Bapuji you were getting married. You were out late and Bapuji insisted we all stay up for you. We had to put boxes of ice in front of the fans and we couldn’t move, it was so hot. When you finally came home, Bapuji told you to come in and asked you in front of everyone what you thought you were doing. You didn’t hesitate. You stood in the doorway and said it as if it was the most natural thing in the world. I am getting married. Like that. It was wonderful. I will never forget the look on Bapuji’s face. You see … I … Charu … she was … she …’

Uncle Pavan seemed about to choke on something inside his throat, and we could see that Pa wanted him to keep talking, but Uncle Pavan couldn’t.

‘It is no use dwelling on things,’ Aunt Ranjan said. She put a hand on Uncle Pavan’s shoulder. ‘Come, Pavan. Bring two more chairs from the garage so we can all sit together.’

Western Lane by Chetna Maroo