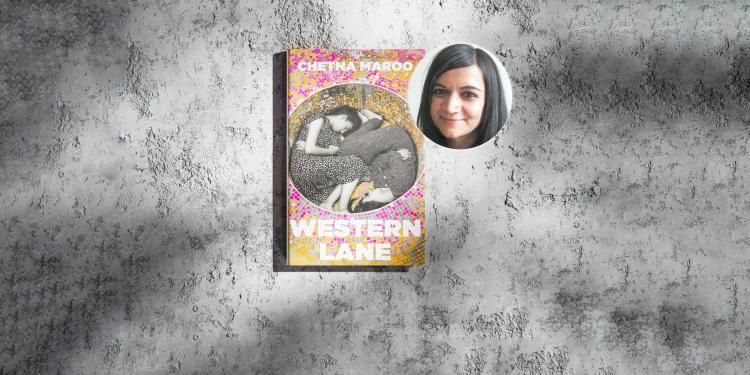

An extract from Western Lane by Chetna Maroo

Chetna Maroo’s tender and moving debut novel about grief, sisterhood, a teenage girl’s struggle to transcend herself – and squash

With Western Lane shortlisted for the Booker Prize 2023, we spoke to Chetna Maroo about sport, sisters and unspoken language

Read interviews with all of the shortlisted and longlisted authors here.

How does it feel to be nominated for the Booker Prize 2023, and what would winning the prize mean to you - especially as one of several debut novelists on the longlist?

It’s feels wonderful. It’s an honour. It’s humbling to see Western Lane amongst all the books that have been longlisted in the history of the prize. I’m still taking that in.

How long did it take to write Western Lane, and what does your writing process look like? Do you type or write in longhand? Are there multiple drafts or sudden bursts of activity? Is there a significant amount of plotting before you begin writing?

It took three years. I write slowly, the first pages in longhand, then typing. I usually try to get each sentence and paragraph sounding right before I go on, reading and editing from the beginning of the story. My own process seems unwise to me because I know I’ll eventually cut sections that I’ve spent weeks or months going over, but I have no other way. I have to trust that the work will benefit in the end from the rhythm and slow quality of this attention.

In the novel we see the world through the eyes of eleven-year-old Gopi. She and her sisters have recently lost their mother. Their pa is bereft and struggling to parent his daughters. At the same time, the girls’ aunt and uncle watch the family, hoping to help Pa by taking one of the girls to raise as their own. As I was writing, I was feeling my way. I didn’t have a plot or outline for the whole novel, but I had a sense that the story would turn on this one question: would Pa bring himself to let one of his daughters go?

Where do you write? What does your working space look like?

I write at my desk at home. To my left is a wardrobe, to my right above my desk the exhibition poster from the Dulwich Picture Gallery’s Tove Jansson retrospective, showing Moomintroll standing in an open window looking out into the dark.

Chetna Maroo

There was something about the squash court itself, about the simple white box: it’s such a surreal, unfamiliar place, where time seems suspended and the outside world can be forgotten

Western Lane is about a young girl and her family who are grieving the loss of a family member, and who channel this grief into squash. Is it fair to call Western Lane a ‘sports novel’?

It’s fair to call it a sports novel. It’s also been called a coming-of-age novel, a domestic novel, a novel about grief, a novel about the immigrant experience. Recently a friend asked me if the book has something of the detective story about it, with Gopi trying to find her way, piecing together the clues of small gestures, actions and fragments of overheard conversations; she has little to go on and since she’s dealing with the mysteries of loss, there are no answers for her. It seemed such an off-the-wall idea but it brought to my mind something Lorrie Moore suggested in her introduction to The Faber Book of Contemporary Stories About Childhood: that the acquisition of knowing and the subject of knowing or not knowing are ‘the unshakeable centre of any childhood story’.

All this to say, I’m not sure how best to categorise Western Lane but I’m interested in how readers read it.

What made you choose sport - and squash in particular - as a way for the family to deal with their grief?

Squash was simply where the story began for me. It started with the feeling of being inside a squash court, with a voice saying, ‘There were three of us.’ I knew there were three sisters in the court. I knew there was a father on the balcony above, instructing the girls. And I knew they all felt the presence of an absent mother. It’s unusual for me to experience such a clear starting impulse for a story. Though I played squash for many years and the game is still vivid in my imagination I don’t know where the connection with this grieving family came from, but I trusted it.

As I began writing, it made sense to me – the way attention is focused outwards in the game, the concentration, the movement of bodies in sync with one another. There was also something about the squash court itself, about the simple white box: it’s such a surreal, unfamiliar place, and in part because of the unfamiliarity it’s a place where time seems suspended and the outside world can be forgotten.

Western Lane by Chetna Maroo

Much of the novel concerns what is unsaid. There are pauses, silences, gestures. Conversations are fragmented, or end almost before they’ve begun. What drove you to invest so much editorial energy in this unspoken communication between characters?

It was natural to write like this once I had felt my way into Gopi’s perspective. This was just the rhythm of life as she experienced it as a child, inside this family dealing with loss.

Perhaps for Gopi and her sisters the way feelings are unspoken is rooted in something deeper. The sisters have always spoken Gujarati, their mother tongue, but not well enough to converse easily with their own mother, and so when she was alive the girls had learned to read her body and to communicate by being physical in her presence. I had the feeling that spoken language had become a wall for the girls, an obstacle to knowing and being known.

Which book or books are you reading at the moment?

I’m reading André Dao’s haunting debut novel Anam. I just read Kathryn Scanlan’s Kick the Latch and Michael Magee’s debut Close to Home. They’re terrific. And I was blown away by the stories in Jamel Brinkley’s A Lucky Man and Thomas Morris’ Open Up.

Do you have a favourite Booker-winning or Booker-shortlisted novel and, if so, why?

The Remains of the Day by Kazuo Ishiguro. And if you’d let me have a Booker-longlisted novel, I’d add My Name is Lucy Barton by Elizabeth Strout. I don’t know what makes these books endure in my mind, but maybe in part it is the feeling of having genuinely encountered the private world of another person, a sensibility – the narrator’s or the author’s, perhaps both.

Chetna Maroo

© Graeme Jackson