Long read

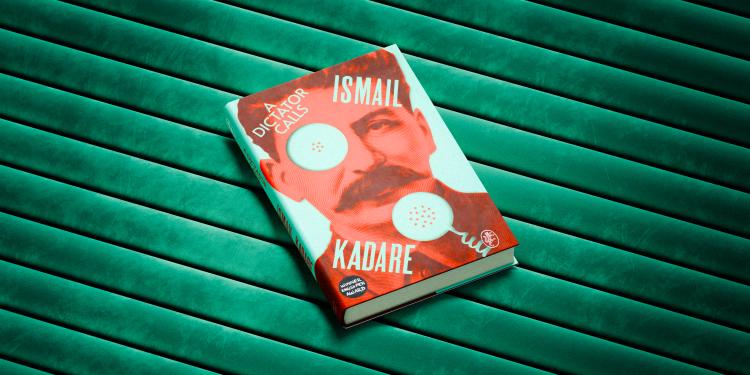

Ismail Kadare’s novel is a fascinating meditation on Soviet Russia, authoritarianism, power structures and the relationship between writers and tyranny

Whether you’re new to A Dictator Calls or have read it and would like to explore it more deeply, here is our comprehensive guide, featuring insights from critics, our judges and the book’s author and translator, as well as discussion points and suggestions for further reading.

In June 1934, Joseph Stalin reportedly telephoned the famous novelist and poet Boris Pasternak to discuss the arrest of Pasternak’s fellow Soviet poet Osip Mandelstam – a man who had expressed criticism of the Soviet regime. In a fascinating combination of dossier facts, dreams and memories Ismail Kadare, winner of the inaugural International Booker Prize, reconstructs the three minutes they spoke and the aftershocks of this tense, mysterious moment in modern history. Weaving together the accounts of witnesses, reporters, the KGB and contemporary writers, Kadare tells a gripping story of power and political structures, of the relationship between writers and tyranny. The telling brings to light uncanny parallels with Kadare’s experiences writing under dictatorship (that of Albanian leader Enver Hoxha), when he received an unexpected phone call of his own.

Joseph Stalin, former leader of the Soviet Union

© Hulton Deutsch / Getty ImagesJoseph Stalin

Joseph Stalin (1878-1953) was the secretary-general of Russia’s Communist Party and dictator of the Soviet Union between 1929 and 1953. Under his brutal and uncompromising rule, the country was transformed at pace into a modern industrial superpower and military giant. While often promoting an image of himself as a great national hero and benevolent leader, Stalin led with brute force and terror, enacting strategies leading directly to the deaths of millions of ordinary Russians, while despatching hundreds of thousands of people to the gulags for opposing Communism. Deeply suspicious and increasingly paranoid, he operated in a climate of fear and tyranny, and would famously crush dissent and eliminate rivals.

Boris Pasternak

Boris Leonidovich Pasternak (1890-1960) was a Russian poet and novelist who is best known in the West for his 1957 novel Doctor Zhivago, which led to him being offered the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1958 – an award he felt compelled to decline, due to the furore surrounding the book, which was banned in Russia until 1987. In 1934, the year of the phone call documented in A Dictator Calls, Pasternak was considered the premier Soviet poet and, among other things, represented the Soviet Union overseas at an international antifascist congress for the defence of culture.

Russian author Boris Pasternak in the study of his home near Moscow

© Jerry Cooke / Getty ImagesIsmail Kadare, born on 28 January, 1936 in Albania, is the country’s best-known poet, novelist and essayist, and one of the world’s foremost literary figures and intellectuals. Since the appearance of The General of the Dead Army in 1965, Kadare has published scores of stories and novels that make up a panorama of Albanian history, linked by a constant meditation on the nature and human consequences of dictatorship. His works, particularly The Monster and The Palace of Dreams (an anti-totalitarian fantasy novel), brought him into frequent conflict with the Albanian authorities, and in 1990 he sought political asylum in France. Nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature 15 times, he has been the recipient of multiple literary awards. In 2005 he won the first ever Man Booker International Prize, awarded for his full body of work; in 2020 he won the Neustadt International Prize for Literature. One of the Neustadt Prize jurors noted: ‘Kadare is the successor of Franz Kafka. No one since Kafka has delved into the infernal mechanism of totalitarian power and its impact on the human soul in as much hypnotic depth as Kadare.’ His works have been translated into over 40 languages, and he now divides his time between Paris and Tirana.

John Hodgson, who was born in 1951, taught at the Universities of Pristina and Tirana after studying English literature at Cambridge and Newcastle. He has worked as a translator and interpreter at the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia in The Hague. He has translated five novels by Ismail Kadare, including The Traitor’s Niche, and several works by Fatos Lubonja, including Second Sentence and The False Apocalypse. He lives in London.

John Hodgson

Rebecca Abrams, Financial Times:

‘What gradually becomes clear is that Kadare is using the Stalin/Pasternak conversation as an extended metaphor to explore the nature of power and the interplay between political power and artistic power. A Dictator Calls is a thought-provoking consideration of the relationship between writers and tyranny, with John Hodgson’s translation gracefully rendering Kadare’s imagination.’

Laura Hackett, Times:

‘The book is not really a novel. It’s more like a cross between memoir, dream diary and historical investigation, in which Kadare trawls through reported versions of what was said during the phone call, with meditations on truth, creativity and tyranny. … Seasoned [Kadare] fans will be enthralled by this very personal meditation on the circumstances in which, against the odds, he still managed to thrive.’

Orlando Bird, Telegraph:

‘A Dictator Calls is slim, but its themes are not. There’s a fine line between uncertainty and obscurity, but the riddles of this novel are still ringing in my mind.’

Cory Oldweiler, Los Angeles Review of Books:

‘There are moments of real brilliance in Dictator, but overall it lacks the sustained highs and dramatic pacing of Kadare’s best later work. Part of this inconsistency is due to the fact that the novel seems unable to fully settle on what it is trying to be, slewing between intense introspection, literary theory, fictionalised autobiography, and historical sleuthing. It is, however, a fitting (possible) coda to a remarkable career, and considering its subject matter, it just might win Kadare the Nobel Prize for Literature, the one major award that he has never received.’

‘The core of this brilliant exploration of power is an analysis of 13 versions of a three-minute telephone conversation between the Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin and novelist Boris Pasternak in 1934. Each of these is an attempt to understand or justify Pasternak’s troubling, ambiguous response from a slightly different point of view. The book begins with what seems like autobiographical memories of Kadare’s time as a student in Moscow, setting the tone which hovers continually between fiction and non-fiction, between what is real and what is invented. Kadara explores the tension between authoritarian politicians and creative artists – it is a quest for some kind of definitive truth where none is to be found.’

The International Booker Prize 2024 Judges; William Kentridge, Natalie Diaz, Eleanor Wachtel, Aaron Robertson and Romesh Gunesekera.

Hugo Glendinning‘I am of the opinion that I am not a political writer, and, moreover, that as far as true literature is concerned, there actually are no political writers. I think that my writing is no more political than ancient Greek theatre. I would have become the writer I am in any political regime.’

Read the full Guardian article here

‘Albanian is simply an extraordinary means of expression – rich, malleable, adaptable. It has modalities that exist only in classical Greek, which puts one in touch with the mentality of antiquity. For example, there are Albanian verbs that can have both a beneficent or a malevolent meaning, just as in ancient Greek, and this facilitates the translation of Greek tragedies, as well as of Shakespeare, the latter being the closest European author to the Greek tragedians. When Nietzsche says that Greek tragedy committed suicide young because it only lived one hundred years, he is right. But in a global vision it has endured up to Shakespeare and continues to this day. On the other hand, I believe that the era of epic poetry is over. As for the novel, it is still very young. It has hardly begun.’

Read the full interview in the Paris Review

‘I have created a body of literary work during the time of two diametrically opposed political systems: a tyranny that lasted for 35 years (1955-1990), and 20 years of liberty. In both cases, the thing that could destroy literature is the same: self-censorship.’

Read the full interview in the Financial Times

‘For a writer, personal freedom is not so important. It is not individual freedom that guarantees the greatness of literature, otherwise writers in democratic countries would be superior to all others. Some of the greatest writers wrote under dictatorship – Shakespeare, Cervantes. The great universal literature has always had a tragic relation with freedom. The Greeks renounced absolute freedom and imposed order on chaotic mythology, like a tyrant. In the West, the problem is not freedom. There are other servitudes – lack of talent, thousands of mediocre books published every year.’

Read the full interview in the Independent

Ismail Kadare

© Ulf Andersen/Getty ImagesThe book offers multiple reasons for why Stalin might have called Pasternak. By the end, have you reached your own view? Why do you think Stalin made the phone call?

At one point in the book, Kadare exclaims: ‘Anybody who thinks at first that thirteen versions are too many, may by the end of the case think that these are insufficient’. Why do you think the author chose to record so many different accounts of the phone call when, as he writes himself, ‘two would be enough to create confusion’. Does having so many versions of the same events lead us closer to the truth, or take us further from it?

The second half of the book, which is set in 2015, takes the form of an extended essay by Kadare in which he analyses each of the 13 accounts of the telephone call. With that in mind, and with the book’s other autobiographical elements, would you say it’s accurate to call A Dictator Calls a novel?

The book is partly inspired by Kadare’s own encounters with tyranny, which included a phone call from Albania’s Stalinist dictator Enver Hoxha several decades ago. It has also been argued that the book is a sequel of sorts to Kadare’s 1978 work Twilight of the Eastern Gods, which was based on his experiences in Moscow in the late 1950s. What do you think compelled Kadare to write this book now, and to what extent might he have been inspired by the emergence of tyrannical leaders around the world?

The book can be read as an exploration of the conflicts between political and artistic power, and Kadare offers stark comparisons between the two. Cory Oldweiler in the LA Review of Books points to the following line as encapsulating not just the novel but Kadare’s theory of art in general: ‘Because art, unlike a tyrant, receives no mercy, but only gives it’. Would you agree that this line is central to our understanding of the book?

Pasternak and Stalin: what was said - History Today

Joseph Stalin: national hero or cold-blooded killer, BBC Teach

How Joseph Stalin rose to power - Britannica

Why Boris Pasternak rejected his Nobel Prize - JSTOR

A profile of Ismail Kadare - Historical Novel Society

If you enjoyed this book why not try…

Doctor Zhivago by Boris Pasternak

The Traitor’s Niche by Ismail Kadare

Twilight of the Eastern Gods by Ismail Kadare

The Story of Russia by Orlando Figes