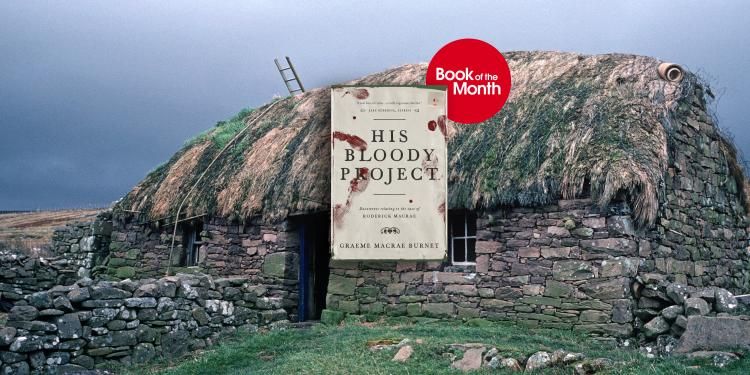

Reading guide: His Bloody Project by Graeme Macrae Burnet

Shortlisted for the Booker Prize in 2016, His Bloody Project reveals the provisional nature of truth through a fictional 19th-century triple murder in a remote Scottish crofting community

Graeme Macrae Burnet’s historical novel tells the story behind a fictional 19th-century triple murder in a remote crofting community. Read an extract from our September Book of the Month here

In 1869, Roderick Macrae was accused of the brutal slaying of three people, in a murder trial that gripped the British public and shocked the nation. Roderick’s memoir, along with court transcripts, medical reports, police statements and newspaper articles, show that he readily admitted his guilt. But do they reveal just why a young man would commit the most atrocious acts of violence? Why didn’t he defend himself more vigorously, or try to cover up the crime? And will he hang?

Published in the UK by Saraband

I am writing this at the behest of my advocate, Mr Andrew Sinclair, who since my incarceration here in Inverness has treated me with a degree of civility I in no way deserve. My life has been short and of little consequence, and I have no wish to absolve myself of responsibility for the deeds which I have lately committed. It is thus for no other reason than to repay my advocate’s kindness towards me that I commit these words to paper.

Mr Sinclair has instructed me to set out, with as much clarity as possible, the circumstances surrounding the murder of Lachlan Mackenzie and the others, and this I will do to the best of my ability, apologising in advance for the poverty of my vocabulary and rudeness of style.

I shall begin by saying that I carried out these acts with the sole purpose of delivering my father from the tribulations he has lately suffered. The cause of these tribulations was our neighbour, Lachlan Mackenzie, and it was for the betterment of my family’s lot that I have removed him from this world. I should further state that since my own entry into the world, I have been nothing but a blight to my father and my departure from his household can only be a blessing to him.

My name is Roderick John Macrae. I was born in 1852 and have lived all my days in the village of Culduie in Ross-shire. My father, John Macrae, is a crofter of good standing in the parish, who does not deserve to be tarnished with the ignominy of the actions for which I alone am responsible. My mother, Una, was born in 1832 in the township of Toscaig, some two miles south of Culduie. She died in the birthing of my brother, Iain, in 1868, and it is this event which, in my mind, marks the beginning of our troubles.

Inverness Castle and Sheriff Court, built as a court house and prison in the mid 1800’s

© Jane Barlow/PA Images/AlamyMy initial impression of R—— M—— was not entirely negative. In his general bearing, he was certainly of low physical stock, but he was not as repellent in his features as the majority of the criminal class, perhaps on account of not breathing the rank air of his urban brethren. His complexion, however, was pallid, and his eyes, while alert, were close-set and capped by thick eyebrows. His beard grew sparsely, although this may have been due to his relative youth, rather than any hereditary deficiency. In his discourse with Mr Sinclair, he appeared quite lucid, but I noted that the advocate’s questions were frequently of a leading nature, requiring the prisoner only to offer confirmation of what had been suggested to him.

I dismissed the advocate and in the presence of the gaoler directed the prisoner to remove his clothes. This he did without protest. He stood before me quite without shame, and I commenced a detailed examination of his person. He stood 5 feet 4½ inches tall, and was of smaller than average build. His chest was disproportionately protruding – what in layman’s terms would be called ‘pigeon-chested’ – and his arms longer than average. The upper- and forearms were well developed, no doubt as a result of his life of physical labour. The hands were large and calloused, with exceptionally long fingers, but there was no evidence of webbing or other abnormalities. His torso was hirsute from the nipples to the pubis, but he was quite hairless on the back and shoulders. His penis was large, though within the normal range of dimensions, and the testicles properly descended. His legs were scrawny, and when asked to walk the length of the cell (admittedly not a great distance) his gait appeared somewhat rolling or lop-sided, suggesting an asymmetry in his bearing. This may have been due to some injury sustained at an earlier time, but when asked, the prisoner was unable to furnish me with any explanation.

I carried out a detailed inspection of the subject’s cranium and physiognomy. The forehead and brow were large and heavy, while the skull was flat on top and markedly obtruding to the back. On the whole, the cranium was quite mis-shapen and not dissimilar to many of those I had examined in my capacity as prison surgeon. The ears were considerably larger than average, with large, flattened lobes.1

As to the visage: the eyes, as already noted, were small and deep-set, but alert and darting. The nose was protuberant, though admirably straight; the lips thin and pale. Likewise, the cheekbones were high and prominent as, it has recently been pointed out, is often the case among the criminal breed. The teeth were quite healthy and the canines not preternaturally developed.

R—— M—— thus shared a certain number of traits with the inmates of the General Prison (these being chiefly, the mis-shapen cranium, unappealing facial features, pigeon chest, elongated arms and ears). In other respects, however, he was a healthy and well-developed specimen of the human race and if one were to observe him in his natural environment, one would not instinctively mark him out as a member of the criminal class. From this point of view, he formed an interesting subject and one which I was curious to study further.

I allowed the prisoner to dress and put a few simple questions to him. He was entirely unresponsive. He appeared at times not to have heard my questions, or pretended not to have done so. I suspect he was well aware of what was being asked, but refused to answer, for motives of his own. Such a strategy did, however, suggest that the subject was not an outright imbecile and was capable of some reasoning, flawed or otherwise. Nevertheless, I saw no purpose in prolonging my enquiries in the face of this stubborn attitude, and had the gaoler release me from the cell.

In the 19th century craniometry was purported to determine character, personality traits, and criminality on the basis of the shape of the head and skull

© adoc-photos/Corbis via Getty ImagesFather twisted his cap in his hands and then, as if realising that this action did not contribute to a favourable impression, abruptly ceased and placed his hands at his sides.

‘I wish to see the regulations,’ he said.

The factor looked at him curiously for a few moments, and then turned his gaze towards me, as if I might be able to explain my father’s words.

‘You wish to see the regulations?’ he repeated slowly, his hand stroking his whiskers.

‘Yes,’ said my father.

‘Of which regulations do you speak?’

‘The regulations under which we exist,’ he said.

The factor shook his head curtly. ‘Forgive me, Mr Macrae, I’m not sure I follow.’

My father was now quite confused. Clearly he had not expected to meet with any such obfuscation and naturally he assumed the fault was his for not expressing himself with sufficient clarity.

‘My father,’ I said, ‘is referring to the regulations under which our tenancies are governed.’

The factor looked at me with a serious expression. ‘I see,’ he said. ‘And why, may I ask, do you wish to see these “regulations”, as you call them?’

He looked then from myself to my father and I had the impression that he was amusing himself at our expense.

‘So that I might know when we are transgressing them,’ my father ventured eventually.

The factor nodded. ‘But why?’

‘So that we might avoid any black marks against our names or penalties for breaking them,’ said my father.

At this the factor leaned back in his chair and tutted loudly.

‘So, if I understand you correctly,’ he said, clasping his hands under his chin, ‘you wish to consult the regulations in order that you might break them with impunity?’

My father’s eyes were downcast and I had the impression that they were becoming quite watery. I cursed him for placing himself in this situation.

‘Mr Macrae, I applaud your audacity,’ said the factor, spreading his hands.

‘What my father wishes to express,’ I said, ‘is not that he seeks to disobey the regulations, rather that by properly familiarising himself with them, he might avoid breaking them.’

‘It seems to me,’ persisted the factor, ‘that a person wishing to consult the regulations could only wish to do so in order to test the limits of the misdemeanours he might commit.’

My father was by this time quite lost and to bring an end to his distress, I told the factor that our visit had been misguided and we would not trouble him any further. The factor however waved away my attempts to bring the interview to an end.

‘No, no, no,’ he said, ‘that will not do at all. You have come here, first of all, making accusations against your village constable, and, secondly, with the stated aim of seeking to avoid punishment for breaking the regulations. You cannot expect me to let matters rest at that.’

Abandoned croft, Applecross peninsula

© Christopher Drabble/AlamyThe factor, seeing that my father was incapable of further discourse, now addressed himself entirely to me. He pulled his chair closer to his desk, selected one of the ledgers and opened it. He turned a few pages and then ran his finger down a column. After reading a few lines, he returned his gaze to me.

‘Tell me, Roderick Macrae,’ he said, ‘what are your ambitions in life?’

I replied that my only ambition was to help my father on the croft and to take care of my siblings.

‘Very commendable,’ he said. ‘Too many of your people have ideas above their station these days. Nevertheless, you must have thought about leaving this place. Are you not minded to seek your fortune elsewhere? An intelligent young man like yourself must see that there is no future for you here.’

‘I do not wish my future to be anywhere other than Culduie,’ I said.

‘But what if there is no future?’

I did not know how to respond to this.

‘I will tell one you thing quite frankly, Roderick,’ he said, ‘There is no future here for agitators or criminals.’

‘I am neither of these things,’ I replied, ‘and nor is my father.’

The factor then looked meaningfully down at the ledger in front of him and tipped his head to one side. Then he loudly closed the book.

‘Your rent is in arrears,’ he said.

‘In common with all our neighbours,’ I replied.

‘Yes,’ said the factor, ‘but your neighbours have not presented themselves here as if they are somehow the injured party. It is only due to the lenience of the estate that you remain on the land at all.’

I took this warning to imply that the ordeal was over and nudged my father, who had been standing those last few minutes as if in a trance. The factor stood up.

I turned to go, but my father stood his ground.

‘Am I to understand then that we may not see the regulations?’ he said.

The factor seemed amused rather than angered by my father’s question. He had taken three or four paces from behind his great desk, so that he now stood only a few feet from us.

‘These regulations that you speak of have been followed since time immemorial,’ he said. ‘No one has ever felt the need to “see” them, as you put it.’

‘Nevertheless …’ said my father. He raised his head and looked the factor in the eye.

The factor shook his head and gave a little laugh through his nose.

‘I’m afraid you are labouring under a misapprehension, Mr Macrae,’ he said. ‘If you do not take the crops from your neighbour’s land, it is not because a regulation forbids it. You do not steal his crops, because it would be wrong to do so. The reason you may not “see” the regulations is because there are no regulations, at least not in the way you seem to think. You might as well ask to see the air we breathe. Of course, there are regulations, but you cannot see them. The regulations exist because we all accept that they exist and without them there would be anarchy. It is for the village constable to interpret these regulations and to enforce them at his discretion.’

Colbost Croft Museum, Skye

© Arterra/Universal Images Group via Getty Images