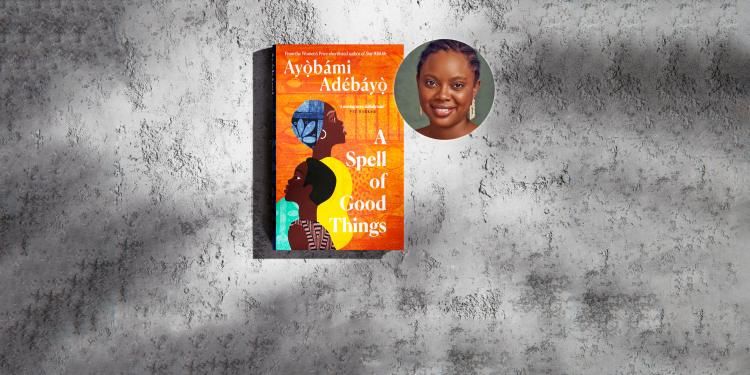

Read the Booker Prize 2023 longlist: an extract from A Spell of Good Things by Ayọ̀bámi Adébáyọ̀

A dazzling story of modern Nigeria and two families caught in the riptides of wealth, power, romantic obsession and political corruption

With A Spell of Good Things longlisted for the Booker Prize 2023, Ayọ̀bámi Adébáyọ talks about how impulse strikes when she’s observing others, and the literary traditions that have nourished her as a writer

Read interviews with all of the longlisted authors here.

How does it feel to be nominated for the Booker Prize 2023?

It’s such a pleasure and privilege for A Spell of Good Things to be recognised in this way. I’m grateful that more readers will discover the novel as a result.

What would winning the prize mean to you?

To actually win? The prospect is almost unimaginable. I do know I would be happy to have made my mother proud. She has made my life possible in ways I might write about in detail someday if she permits. One detail that is relevant here is that whenever she was in the UK for a fellowship or conference, she would return with a Booker Prize-winning book as a gift for me. Which was how I got copies of Kiran Desai’s The Inheritance of Loss, Anne Enright’s The Gathering, Aravind Adiga’s The White Tiger, Hillary Mantel’s Wolf Hall, Howard Jacobson’s The Finkler Question and more.

How long did it take to write A Spell of Good Things, and what does your writing process look like? Do you type or write in longhand? Are there multiple drafts or sudden bursts of activity? Is there a significant amount of research and plotting before you begin writing?

I started working on it in 2013 but I took a break from it for about a year after my debut novel was published. It took about seven to eight years. The process depends on the stage I’m in with the work. When I’m working on the first draft, my goal is usually to get to the end or a stand in for it. That is usually quite quick, easy to schedule and could take under a year.

After that, the real work begins. I go over the book repeatedly, section by section, chapter by chapter, page by page, and often sentence by sentence. It is hard for me to plan that stage or anticipate how long it might take or what the rhythm might be like. While I mostly work on a computer, I write in longhand whenever I feel stuck. There’s usually a notebook next to me when I’m working. I use it to doodle, make notes or test out sentences.

Ayọ̀bámi Adébáyọ̀

© Tomiwa AjayiMost of the characters in the book are bilingual and a few speak only Yorùbá. I had to consider how to carry this over into a novel written in English

Where exactly do you write? What does your working space look like?

I have a home office of sorts in Lagos. My writing desk is connected to a bookshelf that extends from wall to wall, and there’s an ironing board in a corner of the room. There is also some framed art on the wall. My favourite is a mock cover of A Spell of Good Things. My husband gave it to me when I was wondering if I’d ever finish writing the book. I love reading in that space, but I write pretty much anywhere.

In A Spell of Good Things you vividly illustrate a wealth and class divide in Nigerian society, with both sides undermined by abuses of power, greed and violence. What drew you to these issues as a novelist, and in writing about them was there a message you wished to impart to the reader?

The impulse to write often strikes when I’m observing others. Something in a face or manner grabs my attention. It is rare for me to write about it immediately because I can tell that I’m only glimpsing a shadow. The thing itself might stay hidden for days or even a few years. Ideas, especially the ones that become novels, come to me before I am ready for them. The wait before I write the first sentence is twofold. I wait for the figure casting the shadow I’ve glimpsed to come into view. Then, I wait for my skill as a writer to match up to the demands I feel a story has placed on me.

At some point in 2012 or 2013, I was on my way home from work and there was traffic on my usual route. The bus driver then drove us through a neighbourhood I’d never been in and found almost unrecognisable. This was in the town my family had lived in since I was eight. A place I thought I knew. Yet, there I was in a neighbourhood more decrepit than I would have believed existed so close to mine. This experience informed the novel in several ways. It shaped how the story developed into a book about those who can afford to be blind to what’s in front of them and those who cannot.

Despite her privileged background and career prospects as a doctor, Wuraola, one of the book’s central characters, is still a woman who still faces patriarchal barriers and societal expectations. What made you want to explore these issues in the novel, and how much of it was informed by personal experience?

After one of the events for my debut novel in Lagos, a man came to me and asked if I was married. I told him I wasn’t. He then spent the next few minutes explaining how none of the things I’d accomplished really mattered until I was married. I found the whole exchange hilarious in the moment. Later, I wondered about what fuelled such audacity and how his words might have affected a different person. Though I was already working on A Spell of Good Things then, that interaction certainly strengthened the desire to highlight how certain expectations can be insidious.

A Spell of Good Things by Ayọ̀bámi Adébáyọ̀

The prose in A Spell of Good Things often uses Yorùbá diacritics and dialect, with colloquial dialogue, usually without explanation for Western readers. Was this authenticity within the prose important to you?

It was very important. Most of the characters in the book are bilingual and a few speak only Yorùbá. I had to consider how to carry this over into a novel written in English. Considerations around language are critical for any writer, but in my instance, this is threaded through with the fact that always there is another language pulsing through the English I write. I think it often stands out when I am translating dialogue, since I am trying to replicate not only semantics but also rhythm and syntax.

In this novel, where I don’t explain the Yorùbá, it was also important that I always contextualise in a way that gives any reader sufficient access. It is a book about contemporary Nigeria, one that I hope will be read widely by Nigerians. So, I was also thinking of fellow citizens who don’t speak my own mother tongue. How someone like my husband, who is Igbo, might come to the book.

I am a Yorùbá woman writing in English, mostly about Yorùbá people. The metaphors with which many of the characters would articulate their lives shape the language. With each book and character, I ask myself how the writing can honour these realities. Only two books in, my experience is that the answers are different with each attempt.

Which book or books are you reading at the moment?

Stephen Buoro’s The Five Sorrowful Mysteries of Andy Africa and Jenn Ashworth’s Notes Made While Falling.

Do you have a favourite Booker-winning or Booker-shortlisted novel and, if so, why?

I have several favourites. Chinua Achebe’s Anthills of the Savannah was his last published novel and showcases all the skill and wisdom of the previous four, it is one to read and reread. Arundhati Roy’s The God of Small Things was the first winner my mum bought for me. I read it in two days and still treasure it. I read Claire Keegan’s Small Things Like These this year and know already that it is one I will revisit again.

You’re the sixth Nigerian novelist nominated for the Booker in its history, with Ben Okri being the only Nigerian winner. How does it feel to be part of this lineage of Nigerian writers and is there a lot of exciting fiction coming out of Nigeria at the moment?

I feel deeply honoured. A Spell of Good Things highlights the wonder of books, the complexities of access to them and the multiple literary traditions that have nourished me as a writer. Books by Nigerian writers are a major part of that. As an homage of sorts each section of this book is subtitled after a novel by another Nigerian writer. There is a lot of exciting work being published now, and as a reader I hope for much more.

Ayọ̀bámi Adébáyọ̀

© Tomiwa Ajayi