Jeremy Tiang interview: ‘Everyone should translate, it's a wonderful experience'

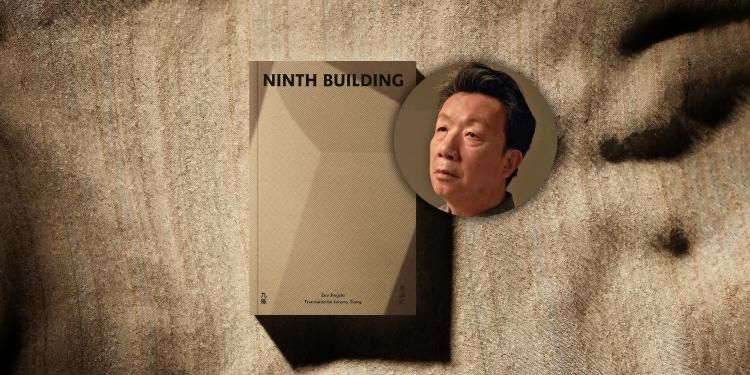

Longlisted for the International Booker Prize 2023, translator Jeremy Tiang talks about being nominated for Ninth Building in an exclusive interview

With Ninth Building longlisted for the International Booker Prize 2023, the author talks about why he prefers to write with a pen than a keyboard – and how his book has travelled through time

Read interviews with all of the longlisted authors and translators here.

How does it feel to be longlisted for the International Booker Prize 2023, and what would winning mean to you?

It feels great. I’m thankful for the recognition that Ninth Building has gotten. It signifies that 13 years after the Chinese publication, the English translation has allowed it to travel through time. I hope it attracts many different readers.

What were the inspirations behind the book? What made you want to tell this particular story?

There’s an ancient Chinese saying, about a child who has lost their mother: ‘I dream of mother, she was like a gust of wind’. A lonely child sees his mother in a dream at night; everything returns to normal in the daylight. He thought his mother came to see him.

In the early 1990s, my childhood felt like it had been a gust of wind behind the trees. I used to spend my days being lost: What should I write? Whatever I wrote was wrong. It was impossible to get rid of my childhood back then. So I just wrote like that. I wrote for myself. I wrote to let go of my childhood.

How long did it take to write the book, and what does your writing process look like? Do you type or write in longhand? Are there multiple drafts or sudden bursts of activity? Is the plot and structure intricately mapped out in advance?

I always use a ballpoint pen when I write. I’m from that generation. Chinese calligraphy has been around for thousands of years, and most Chinese classics were written with a calligraphy brush. During the previous generation in the 1930s, writing left to right with pens (fountain pens, pencils, ballpoint pens) began. Then in the ‘80s, after a Chinese language input method for computers was invented, it brought about writing with a keyboard. It became convenient to write on computers, but the pace and rhythm was different from Chinese written with a calligraphy brush. The change of writing tools brought about a big change in literature. And my writing is situated in the middle of this transition from pen to keyboard. I’ve tried to write with a keyboard, but I couldn’t continue. So until now, I’ve been using a pen to write. When I write using a pen, I can feel the expression of my mood and feelings with the movement of letters with just one glance. The letters that appear on a computer are stringed along, immobile and still. It made me think the machine participated in my writing.

I wrote Ninth Building mostly from 1989 to 1993. And then revisited it in 1996, revising a small part of it.

Zou Jingzhi

When I write using a pen, I can feel the expression of my mood and feelings with the movement of letters with just one glance

Where do you write? What does your working space look like?

In the ‘80s and ‘90s, I lived with my wife and daughter in a row of public housing assigned by my wife’s work unit; a room of more than ten square metres in which we cooked food in a small kitchen. I usually wrote and invited guests in that kitchen so I wouldn’t disturb my family members and they wouldn’t disturb me. Most of Ninth Building was written there. I wrote 20 pieces of work during that time.

What was the experience of working with the book’s translator, Jeremy Tiang, like? How closely did you work together on the English edition? Did you offer any specific guidance or advice? Were there any surprising moments during your collaboration, or joyful moments, or challenges?

I met Jeremy just once, in the spring of 2012, after the Chinese edition had been published for a year. My two writer friends were walking in Xiangshan in Beijing with Jeremy, and when they were passing by my home, they came by for tea. After knowing that Jeremy can read Chinese, I gave him a copy of Ninth Building and a collection of my theatre scripts. Then in 2013, Jeremy received a PEN grant for his translated manuscript of Ninth Building. I called him with the help of a friend to express my thanks. Then, in 2022, Honford Star published Ninth Building in English. Our collaboration was smooth, and everything fell into place. Looking at the outcome, this is all because of Jeremy’s outstanding translation and collaboration.

I’m thankful to Ninth Building’s British and Chinese publishers and to the [International] Booker Prize. They all help share different literature from across the world, benefiting everyone!

Jeremy Tiang