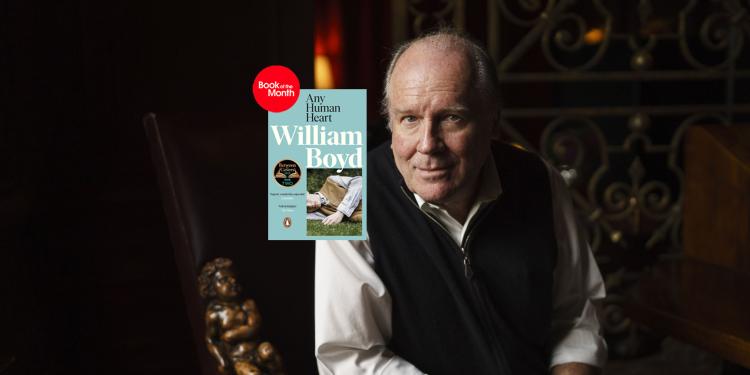

Win a copy of Any Human Heart by William Boyd – and a Booker Prize tote bag

Win one of five bundles including a copy of our December Book of the Month, Any Human Heart by William Boyd, plus a limited-edition Booker Prize tote bag

William Boyd has written 17 novels and multiple collections of stories, spanning fictional biographies, foreign adventures and even a James Bond thriller. So where’s the best place to start with the twice Booker Prize-nominated author?

If you ask William Boyd – author of this month’s Booker Prize Book of the Month, Any Human Heart – which of his 17 novels you should read first, you’ll get no help. ‘There are no runts of the litter as far as I’m concerned,’ he said when I interviewed him for The Irish Times in 2022. ‘Each novel in a way has turned out as I hoped it would.’

This is a confidence that most writers would kill for, and it comes through in his vigorous, entertaining novels. Boyd brings his exceptionally fertile imagination to every book he writes, and always gives the sense of being fully committed to his stories and characters. But as with any long literary career, there are peaks and troughs, and – just as importantly – recurring themes and motifs in his work. Here is our guide to where to start reading William Boyd’s books.

Any Human Heart is the best-loved of Boyd’s novels, and with good reason. We feel affection for the irrepressible Logan Gonzago Mountstuart: we get the secrets of his most private thoughts from these ‘intimate journals’, and we live with him for a whole lifetime, from his schooldays in 1923 to his death in 1991. The book spans the 20th century: we learn new things about those decades, and recognise others: ‘I was there!’ How could we not love him, whatever he gets up to, from leftist terrorism to questionable love affairs?

Boyd calls it a ‘whole life’ novel, and over the last 40 years, he has made a speciality out of them. The best of them is The New Confessions (1987), Boyd’s first attempt at the form, and still a high point in his output. Like Any Human Heart, it spans most of the last century (its hero was born in 1899 and the story runs to 1972), but with two key differences: first, it takes the form of an autobiography rather than a diary; and second, narrator John James Todd is – in the word of his creator – ‘an egomaniac who behaves appallingly badly’.

A film-maker who believes himself under-appreciated, Todd has a sharp tongue, as we see right from the irresistible opening line: ‘My first act on entering this world was to kill my mother.’ (She died in childbirth.) He’s vain and stubborn: but it is these qualities that keep him going when he struggles with his dream of making a film based on Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s Confessions. (Rousseau’s mother also died at the moment of his birth.) The form of a fictional autobiography gives the book a structural advantage over Any Human Heart: where Logan Mountstuart’s account is written in the honest moment, John James Todd can be sneaky and deceptive in how he portrays the past. He keeps the reader on their toes, through two world wars and the humiliation awaiting a self-declared genius in Hollywood; and his story features the recurring Boyd theme of the importance of luck – good and bad – in every life. It’s a novel of exceptional quality, and set the bar for the rest of Boyd’s career.

Boyd has written two other ‘whole life’ novels: Sweet Caress (2015) about photographer Amory Clay, and The Romantic (2022) about adventurer Cashel Greville Ross (and which varies the formula by covering the 19th century rather than the 20th). If neither quite lives up to Any Human Heart or The New Confessions, it’s only because the standard he set himself is so high.

The New Confessions by William Boyd

For a time – mostly in the 1980s and 90s – Boyd had a Graham Greene-ish appetite for setting his novels in exotic locations. One of the best – and certainly the most warm-hearted and affecting – is The Blue Afternoon (1993), which takes place largely in Manila in the early years of the 20th century. It features Dr Salvador Carriscant, ‘the most celebrated surgeon in the Philippines’, who helps police find a killer – but who is also one half of the most touching love story Boyd has written. The Blue Afternoon has a lot to chew on, including early aviation, surgery, architecture, the Philippine-American War, and a portrayal of Manila that is so convincing that Boyd once received a letter from a resident asking him when he had lived there. (In fact, he had never been.)

The Blue Afternoon by William Boyd

Born in Ghana and raised in Nigeria – ‘until the age of 22, I regarded West Africa as my home’, he told The White Review in 2011 – Boyd was attracted to Africa as a setting in much of his early work. (He initially wanted to set The Blue Afternoon around the Boer War, but thought, ‘I mustn’t go to Africa again.’) The best of the African books are An Ice-Cream War (shortlisted for the Booker Prize in 1982) and Brazzaville Beach (1990). The former is about a little-known campaign in East Africa during the First World War, which ‘continued after the Armistice because no one told them to stop.’ It opens in Boyd’s best comic style, with an exchange between former President Teddy Roosevelt and his son: ‘What do you think would happen if I shot an elephant in the balls?’ ‘Father, I think it would hurt a great deal.’ But it is a serious novel too, about the futility of human planning in the face of the chaotic forces of war. Brazzaville Beach explores the idea that chimpanzees – like humans, and unlike other animals – fight wars with each other, and asks how far removed we are from them. It is a fan favourite: ‘I still get letters about it,’ Boyd said this year in The Mirror and the Road: Conversations with William Boyd.

(A word about names: you may have noticed – Hope Clearwater, Salvador Carriscant, Logan Mountstuart – that Boyd likes to give his characters unusual names. This, he told The Irish Times, is ‘a trick of the trade – don’t just call them John Smith or Sally Watts. Come up with something a bit individual, and immediately the character starts to live.’ And he uses forenames that sound like surnames – Amory Clay, Lorimer Black, Henderson Dores – because ‘it creates distance from the character’ and means the author can call the character by their first name without sounding too close to them.)

An Ice Cream War and Brazzaville Beach by William Boyd

‘I see myself as a comic novelist,’ Boyd says in The Mirror and the Road. ‘My vision of the world is that it’s absurd and stupid and makes no sense, and attempts to make it make sense are doomed to failure.’ It’s a vision he has pursued throughout his career, with several novels that make pure enjoyment their prime force.

Stars and Bars (1984), the only of Boyd’s novels set wholly in the United States, is a perfect example. An Evelyn Waugh-flavoured story of an innocent abroad, it takes the luckless Englishman Henderson Dores and plants him in America, to see how badly he copes. There’s a sense from the opening lines – ‘Look at Henderson Dores walking up Park Avenue…’ – that he’s a plaything for the author’s, and our, amusement. Cue lots of capers, bordering on antics, involving pleasingly exaggerated characters, like an aggressive dinner party scene (‘OK, so the Reds take over England. Who gives a sick dog’s dump?’) and our hero being chased the length of Manhattan by a lunatic with a knife.

Stars and Bars by William Boyd

Boyd’s first published novel was a comedy too: A Good Man in Africa (1981) has a typically labyrinthine Boyd plot involving bribery, blackmail and adultery, starring the overweight and oversexed Morgan Leafy, a British government employee in Kinjanja (a lightly fictionalised Nigeria). He is not, needless to say, the good man of the title – but if he was, he wouldn’t be half as funny, with a bracing cynicism that recalls not just Waugh but Kingsley Amis too.

Boyd’s commitment to showing his reader a fun time continues today, with his 2020 novel Trio, set in the film industry in the late 1960s. (Novelists love to set their books in adjacent artistic fields, as there are parallels with their own experience of creativity, but the details are sexier than someone sitting at a desk all day.) It’s a rollercoaster story involving an alcoholic writer, a lovelorn actress and a closeted gay movie producer, that asks little of the reader other than to hang on and enjoy the ride.

A Good Man in Africa by William Boyd

Boyd’s experience of film work – he has written almost as many screenplays as he has novels – has given him a sound understanding of what keeps the pages turning and the reader’s heart pumping. After Any Human Heart, he wrote several thrillers: admittedly a fluid category, since Boyd has always, even in other books, been more interested in strong plots than many of his literary contemporaries.

The most celebrated of these is Restless (2006), which gained Boyd a new readership via the Richard & Judy Book Club, and won the Costa Novel of the Year award. (Boyd has won major literary awards infrequently for such an acclaimed author. ‘Even back then I wasn’t that bothered,’ he said, a little unconvincingly, of his debut A Good Man in Africa winning not one but two prizes.) Restless is a story where a young woman discovers that her grandmother was a Russian emigré spy in the Second World War, where its settings (of wartime Britain, of the hot summer of 1976) are as convincing as the Manila of The Blue Afternoon, and where Boyd’s characteristically cheeky blend of fact and fiction (did the British secret service really work undercover to bluff the USA into the war?) keeps the reader guessing in more ways than one.

Restless by WIlliam Boyd

Boyd’s other thrillers are Ordinary Thunderstorms (2009) and Solo (2013). The former, replete with playful clichés of the form (a character dies with the words, ‘Whatever you do, don’t—‘; a chapter ends with ‘And then everything went black’), is an inquiry into how a man in our modern connected world can disappear, and as close to a Hollywood thriller in book form as Boyd has written. The latter is a Hollywood thriller, or might be soon: Solo was a James Bond continuation novel which, unusually for Bond but not for Boyd, was set in Africa. It is one of a series of authorised post-Ian Fleming stories about the world’s most famous spy, the first of which (Colonel Sun) was written in 1968 by future Booker Prize winner Kingsley Amis.

Ordinary Thunderstorms and Solo by William Boyd

In one sense Boyd, although ‘a realist novelist, unapologetically’, has always been interested in playing with form as a writer: Brazzaville Beach switches between first and third person; The New Confessions takes the form of a fake autobiography; and in Any Human Heart, Logan Mountstuart’s journals begin and end with the same unusual word (you’ll have to look it up).

But the place where Boyd most lets his authorial hair down is in his short fiction. He has published four collections of stories, and, he says, ‘I use my short stories as a way of flexing muscles I wouldn’t flex in my novels. You wouldn’t want to spend two years writing a novel to see if [an experiment] worked, but you can do it over a few days with a short story.’

It’s this impulse that has given us stories like ‘Extracts from the Journal of Flying Officer J’, a surreal fantasy set in an alternative England; ‘Long Story Short’, a story about whether the story’s narrator is really William Boyd; ‘Beulah Berlin’, a story in the form of an A-Z of the character’s life; and ‘Lunch’, which concludes with a perfectly grammatical sentence that ends with the word ‘lunch’ three times in a row. (Again, you’ll have to look it up.)

The masterpiece of the experimental Boyd, however, is undoubtedly Nat Tate: An American Artist 1928-1960 (1998). This short book (Boyd claims it is another of his ‘whole life’ novels, which is a stretch) is a fictional biography of a painter Boyd invented, and it was published as an authentic account with the collaboration of people like David Bowie (whose art imprint published it) and Gore Vidal (who provided a cover quote). The paintings of Tate’s which punctuate the text were done by Boyd himself, and the whole joke was revealed only at the book’s London launch.

Nat Tate brings us full circle in Boyd’s work. It was inspired by a Sunday Times review of The New Confessions, where the reviewer found John James Todd’s story so convincing that ‘hypnotised by the realism of its autobiographical form, I found myself rifling through the pages for photographs’. That gave Boyd an idea, and Nat Tate is littered with photos of the fictional artist and real people from the art world, to enhance the subterfuge. And in another delicious connection, the story of Nat Tate in the book comes mostly through the written records of his friend and confidante, an English literary figure that Boyd readers might recognise. It is Logan Mountstuart, ‘whose journals,’ Boyd writes with a twinkle in his eye, ‘I am currently editing’.

Nat Tate: An American Artist 1928–1960 by William Boyd