Video

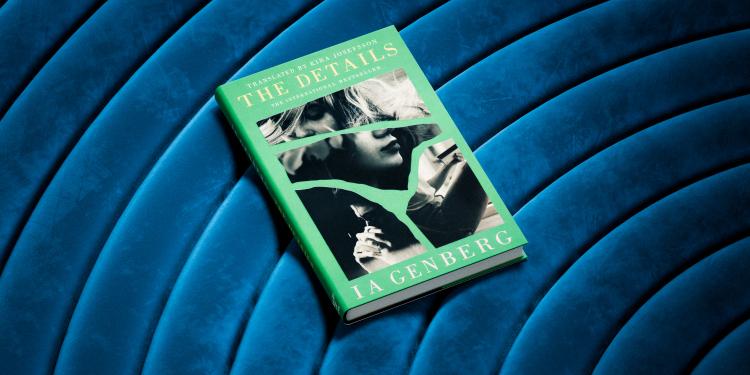

In exhilarating, provocative prose, Ia Genberg reveals an intimate and powerful celebration of what it means to be human

Whether you’re new to The Details or have read it and would like to explore it more deeply, here is our comprehensive guide, featuring insights from critics, our judges and the book’s author and translator, as well as discussion points and suggestions for further reading.

A famous broadcaster writes a forgotten love letter; a friend abruptly disappears; a lover leaves something unexpected behind; a traumatised woman is consumed by her own anxiety. In the throes of a high fever, a woman lies bedridden. Suddenly, she is struck with an urge to revisit a particular novel from her past. Inside the book is an inscription: a message from an ex-girlfriend. Pages from her past begin to flip, full of things she cannot forget and people who cannot be forgotten. Johanna, that same ex-girlfriend, now a famous TV host. Niki, the friend who disappeared all those years ago. Alejandro, who appears like a storm in precisely the right moment. And Birgitte, whose elusive qualities shield a painful secret. Who is the real subject of a portrait, the person being painted or the one holding the brush?

In exhilarating, provocative prose, Ia Genberg reveals an intimate and powerful celebration of what it means to be human. Translated from Swedish by Kira Josefsson.

The narrator

The narrator of The Details is unnamed, yet throughout the narrative, a picture emerges of an intelligent middle-aged woman. She has love affairs with both men and women, all of whom echo and impact upon her life.

Johanna

Johanna is the narrator’s ex-girlfriend and first love, who goes on to become a famous TV host. During their relationship, Johanna gifts the narrator a copy of Paul Auster’s The New York Trilogy in 1996 when she is overcome with malaria after she had been on a trip to the Serengeti. Johanna and the narrator share a love of reading (‘Literature was our favourite game,’ she writes), introducing each other to authors and books, the divergent tastes fostering discussion and debate throughout their relationship.

Niki

Niki was the narrator’s flatmate at university. She consequently disappeared, leaving a lasting impact on the narrator.

Alejandro

Alejandro, a Chilean-German dancer who appeared like a storm, and with whom the narrator had an intense love affair.

Birgitte

Birgitte is the narrator’s mother and her fourth memory. She is described as a woman adrift, with elusive qualities, all shaped by childhood trauma. Birgitte gave birth to the narrator during a ‘psychotic break’, and her behaviours during her childhood inform the narrator’s own cautionary approach to trust.

Swedish author Ia Genberg began her writing career as a journalist. She published her debut novel Sweet Friday in 2012 and another novel, Belated Farewell in 2013. These were followed by the short story collection Small Comfort, and four other tales about money in 2018.

The Details, her first book to be translated into English, was an instant Swedish bestseller and has since sold in 29 territories across the world. She is the winner of the August Prize 2022 and the Aftonbladet Literary Prize 2023.

Ia Genberg

Kira Josefsson is a writer, editor and translator working between English and Swedish.

The recipient of a PEN/Heim grant, she translates some of the most interesting contemporary Swedish voices, like Hanna Johansson, Judith Kiros – and Ia Genberg. Based in Queens, New York, she serves on the editorial board of Glänta, a journal of arts and politics, and regularly writes on US events in the Swedish press.

Kira Josefsson

Catherine Lacey, The New York Times

‘“As far as the dead are concerned, chronology has no import and all that matters are the details,” Genberg writes in the last chapter, and though this isn’t the kind of novel given to spoilers, there are elements here best left for a reader to discover firsthand.

The literal fever that begins the book mirrors the feverish beginnings and endings of these relationships, as well as the fever of reading — how it forces the reader inward, then leaves an invisible imprint in its wake. Genberg’s marvelous prose is also a kind of fever, mesmerizing and hot to the touch.’

Eliza Smith, LitHub

‘It’s difficult to describe the experience of reading Ia Genberg’s English language debut (winner of the August Prize, Sweden’s most prestigious book award) beyond saying that it resembles a fever dream—which is appropriate, given that the narrator herself is in bed with a rising fever, as she recalls four important people from her past […] Genberg’s prose is a feat of characterization, a triumph of lending language and profundity to observations of daily life. At a tight 150 pages, I didn’t read it so much as subconsciously absorb it.’

The New Yorker

‘This elliptical novel, narrated by an unnamed woman who is confined to her bed by a high fever, consists of four character studies. During her illness, the woman picks up a book—an edition of Paul Auster’s “New York Trilogy”—inscribed to her by a former lover. Flipping through it brings back vivid recollections of that woman, whose frosty personality “was part of her—and not as deficiency but as tool, a useful little patch of ice.” These reminiscences lead to others: first of a wayward roommate; then of a “hurricane” ex-boyfriend; and finally of the narrator’s traumatized mother. She relates her textured insights into human nature through small moments. “As far as the dead are concerned,” she muses, “all that matters are the details, the degree of density.”’

‘Ia Genberg writes with a remarkably sharp eye about a series of messy relationships between friends, family and lovers. Using, as she says, ‘details, rather than information’, she gives us not simply the ‘residue of life presented in a combination of letters’ but an evocation of contemporary Stockholm and a moving portrait of her narrator. She has at times a melancholic eye, but her wit and liveliness constantly break through.’

The International Booker Prize 2024 Judges; William Kentridge, Natalie Diaz, Eleanor Wachtel, Romesh Gunesekera and Aaron Robertson.

Hugo GlendinningThe Details is told in only four chapters, each centred on a pivotal person within the narrator’s life. Why do you think the author chose to adopt this structure? Does the focus of each section enhance the reading experience of the novel as a whole?

The Details lacks a conventional plot, with arguably no beginning, middle or end. Many details emerge from a fever dream of the narrator’s memory in a fragmentary and non-linear manner. With its lack of chronology, what role does time play in the novel? How did it give you a sense of perspective throughout, and particularly at the end of your reading?

The synopsis of The Details asks ‘Who is the real subject of a portrait, the person being painted or the one holding the brush?’ After reading the novel, what do you make of this query? Discuss the overarching impression you received of the narrator and whether Genberg intended to write one character study, or five.

During the novel, the narrator notes that we are all ‘traces of the people we rub up against’. To what extent do you agree that these encounters, be they fleeting or prolonged, echo upon us – are we all the sum of many parts?

‘By the time I was staring at the stoop of the brownstone where Paul Auster and Siri Hustvedt lived their lives and wrote their books, I was in a serious relationship with a man who in that moment was eating pancakes with my daughter at a nearby café.’ The Details features an array of literary references, from the moment the narrator picks up The New York Trilogy on page one. ‘There’s not much I can recall from that summer – but I’ll never forget our apartment, the book, or her,’ she says. The author uses literature as a narrative device throughout the novel. What role does she intend it to play, and is she successful in this deployment?

If I Survive You by Jonathan Escoffery

The Years by Annie Ernaux, translated by Alison L Strayer

The New York Trilogy by Paul Auster

The My Struggle series by Karl Ove Knausgaard, translated by Don Bartlett

If I Survive You by Jonathan Escoffery