Video

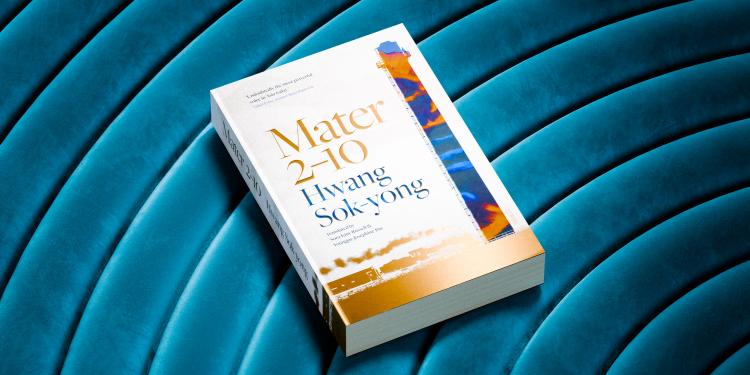

An epic, multi-generational tale that threads together a century of national history, written by one of South Korea’s most important authors

Whether you’re new to Mater 2-10 or have read it and would like to explore it more deeply, here is our comprehensive guide, featuring insights from critics, our judges and the book’s author and translator, as well as discussion points and suggestions for further reading.

An epic, multi-generational tale that threads together a century of Korean history. Centred on three generations of a family of rail workers and a laid-off factory employee staging a high-altitude sit-in, Mater 2-10 vividly depicts the lives of ordinary working Koreans, starting from the Japanese colonial era, continuing through Liberation, and right up to the twenty-first century.

Yi Jino

Yi Jino leads the story within Mater 2-0. He is a mid-fifties factory worker and staunch unionist who has recently been laid off from his job. As a result, he decides to stage a protest and climbs to the top of a large chimney, refusing to be moved. Jino remains there in defiance, attempting to shame the factory owners into negotiating with the union. While there, Jino reminisces and is visited by ghosts of his past – family members, friends, and those who have made an impression on his life; with their life experiences interwoven with Korea’s political history during the Japanese occupation.

Baekman

Jino’s great-grandfather was a railroad worker, a machinist, during the period Korea was colonised by Japan. He had taught himself to read and write, all while learning Japanese working as a clerk and day labourer. He passes his passion for trains and the railroads on to his son and grandson.

Icheol

Icheol is Jino’s granduncle. He is an activist, joining the communist party during the Japanese occupation. As he protests and fights for workers’ rights, he catches the attention of the police and ends up under perpetual scrutiny.

Ilcheol

Ilcheol is Jino’s grandfather. He follows in his father’s footsteps to work on the railways as a train engineer, he initially focuses on his career until the end of the Second World War, when he becomes a union leader. Like his bother, he then becomes a target with the police. Eventually, he defects to the North.

Geumi

Geumi is Jino’s grandmother. She was a precocious child and, unusually for a girl from the country, attended primary school. Geumi had the ability to see ghosts and had psychic-like abilities.

Jisan

Jisan is Jino’s father, and also a railroad worker. He follows his father to the North, only to return as a wounded prisoner of war.

Hwang Sok-yong was born in 1943 and is arguably Korea’s most renowned author. In 1993, he was imprisoned for five years for travelling to North Korea to promote exchange between artists in the two Koreas. The recipient of Korea’s highest literary prizes, he has been shortlisted for the Prix Femina étranger and was awarded the Émile Guimet Prize for his novel At Dusk, which was also nominated for the International Booker Prize. His novels and short stories are published all over the world. Previous novels include Princess Bari, Familiar Things, The Ancient Garden, Mister Han, The Guest, and The Shadow of Arms. His powerful memoir is entitled The Prisoner.

Hwang Sok-yong

© Gary Doak / Alamy Stock PhotoSora Kim-Russell has translated numerous works of Korean fiction, including Hwang Sok-yong’s Princess Bari (Garnet Publishing, 2015), Familiar Things (Scribe, 2017), and At Dusk (Scribe, 2018), which was longlisted for the 2019 Man Booker International Prize.

Winner of the 2019 LTI Korea Award for Aspiring Translators and the 2021 Korea Times Modern Korean Literature Translation Award, Youngjae Josephine Bae’s translations include Imaginary Athens: urban space and memory in Berlin, Tokyo, and Seoul (Routledge, 2020) and A Global History of Ginseng: imperialism, modernity, and orientalism (Routledge, 2022). Her latest translation of the short story ‘Blessings’ by Kang Hwa-gil will be published in the upcoming issue of Azalea: journal of Korean literature and culture. She lives in Seoul, South Korea.

Sora Kim-Russell

© Courtesy Sora Kim-RussellMaya Jaggi, the Guardian

‘Mater 2-10 is a vital reminder that, while the Berlin Wall may have fallen, the Cold War lives on in a divided Korea. It traces the roots of postwar persecution of labour activists smeared as “commies”. Decades of torture of political opponents in Japanese-built prisons are revealed as a “legacy of the Japanese Empire”. Hwang’s aim, he writes, was to plug a gap in Korean fiction, which typically reduces industrial workers to “historical specks of dust”. Not only does he breathe life into vivid protagonists, but the novel so inhabits their perspective that we share the shock and disbelief as their hard-won freedom is snatched away.’

Irish Times

‘This book has “major work by major writer” written all over it, and it is certainly a novel of epic ambition and mostly convincing delivery. It is important not least because of its long perspective in depicting the plight of those marginalised by a succession of colonial influences: Japan, the US and global capitalism.’

Readings.com.au

‘Mater 2-10 is a stunning achievement. It is at once a powerful account that captures a nation’s longing for a rail line that would connect North and South, a magical-realist novel that manages to reflect the lives of modern industrial workers, and a culmination of Hwang’s career — a masterpiece thirty years in the making.’

Patrick McShane, Asian Review of Books

‘The story can be read as either an earnest story with noted sympathy for the workers’ movement and the activism of the Josen Communist Party during the struggle against the Japanese. Indeed the author claims the story was inspired by an aging former activist he met in Pyeongyang during an illegal trip to North Korea. Conversely, it could also be a satire of those who claim to work for the common man, but who are often more involved in esoteric ideological discussion than in actual work, as when the leaders of the communist movement in Korea don’t live in Korea at all and spend far too much time discussing and debating the “Party line” when fellow activists are being tortured to death.’

‘A large and comprehensive book about a Korea we rarely see in the West, blending the sweeping historical narrative of a nation with an individual’s quest for justice. Hwang highlights the political struggles of the working class with the story of a complicated national history of occupation and freedom, all seen through the lens of Jino, on his perch on top of a factory chimney, where he is staging a protest against being unfairly laid-off.’

The International Booker Prize 2024 Judges; William Kentridge, Natalie Diaz, Eleanor Wachtel, Romesh Gunesekera and Aaron Robertson.

Hugo Glendinning‘There was no writing material in jail: there wasn’t even any decent toilet paper. I stored up my experiences in my memory. When I came out of prison I wrote 8 novels in 10 years. There are still ideas I haven’t written yet.

‘I gained a lot from prison. I spent two years on hunger strike and protesting. I read a lot. But then I realised that reading alone is not as good as sharing it. To read, you must also communicate with people. You cannot read in isolation. So I took exercise with the my fellow-inmates and learned to live life everyday. PEN International sent me a book once a month for five years, which improved my English.’

Read more at London Korean Links

‘Seventy years after the liberation from Japan, the peninsula is still divided. We went through the Korean War, which was both a civil war and an international conflict, and Europe, the Far East, indeed the whole world devolved into a state of Cold War… I believe it is vital for us to work to quickly change the status on the Peninsula from one of armistice to one of permanent peace lest we find ourselves in yet another war.’

Read the full interview at The Skinny

Hwang Sok-Yong

In the translators’ note at the beginning of the novel, Sora Kim-Russell and Youngjae Josephine Bae write: ‘It was somewhere around when the characters were forced to change their names and conform to Japanese ways that the hidden violence of translation became more apparent’. As a result, they looked for ways to ‘decolonise their translation’. People’s names, places and objects remain Korean. How do you think this serves the story, and do you feel it cultivated a more authentic, or immersive, reading experience for Mater 2-10?

Mater 2-10 begins with Yi Jino, a factory worker and unionist who has been laid off, staging a ‘sit-in’ on top of an industrial chimney. Discuss what Yi Jino’s protest might be seen to symbolise.

In 1993, Hwang Sok-yong was imprisoned for five years for breaching South Korean security laws for travelling to North Korea to promote exchange between artists. He is a renowned activist and socialist. Where do you see the author’s personal and political beliefs intertwine with the plot of Mater 2-10?

At one point in the novel, Jino is told by Geumi that her brother-in-law used to be a communist. ‘Jino didn’t understand what this meant until he was all grown up, and by then he had come to the bitter realisation that his future had already been decided for him.’ (Page 100.) What is meant by this, and why had his future as a manual worker been pre-determined?

Much of Mater 2-10 is concerned with documenting the real lives of working-class Koreans across generations, particularly the period of 1910 to 1945 when Korea was colonised by Japan. Hwang Sok-yong writes this in a way he terms ‘mindam realism’, with mindam defined as ‘halfway between folklore and plain talk’. Do you think the author is successful in educating the reader on the plight of ordinary Koreans, through this unique blend of oral history spliced with elements of magical realism?

History.com: How Japan Took Control of Korea

History.com: Korean War

At Dusk by Hwang Sok-yong, translated by Sora Kim-Russell

Whale by Cheon Myeong-kwan, translated by Chi-Young Kim

The Vegetarian by Han Kang, translated by Deborah Smith

The Specters of Algeria by Yeo Jung Hwang

Whale by Cheon Myeong-Kwan