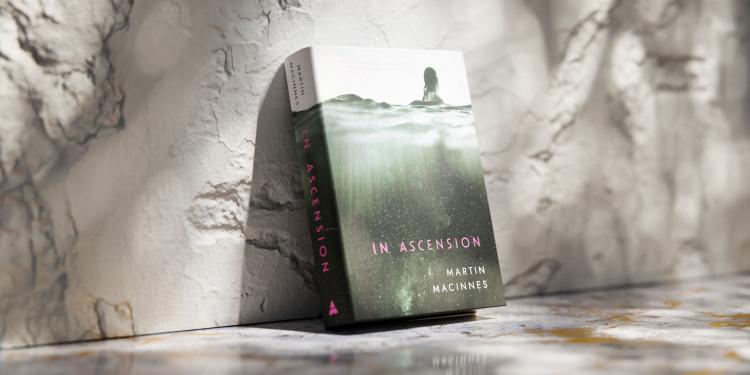

Book recommendations

Exploring the natural world with wonder and reverence, this compassionate, deeply inquisitive epic reaches outward to confront the great questions of existence, while looking inward to illuminate the human heart

Leigh grew up in Rotterdam, drawn to the waterfront as an escape from her unhappy home life. Enchanted by the undersea world of her childhood, she excels in marine biology, travelling the globe to study ancient organisms.

When a trench is discovered in the Atlantic Ocean, Leigh joins the exploration team, hoping to find evidence of Earth’s first life forms. What she instead finds calls into question everything we know about our own beginnings, and leaves her facing an impossible choice: to remain with her family, or to embark on a journey across the breadth of the cosmos.

I looked into imagined depths, the base of the vent broiling with archaea and bacteria, churning through the gases emitted by the opened earth, a cycle of transformation beginning. The possibility of life, mineral into organic, objects creating themselves in a frenzy of feeling, striving not to end, briefly distinct from what surrounds them before coming apart again, back into disparate chemicals. I took a breath, felt a stabbing in my abdomen: anxiety, indigestion, the trailing memory of the illness picked up in the water. I clutched at the pain, grasping myself, and looked back, turning away from the edge and towards the ship, the low roofs of the decks, the clip of the neat doors closing onto snug cabins. I flashed the rest of the dive team an OK sign, kicked backwards from the stern, tumbled into the water.

Something had got inside us, a compulsion, a desire, a need to return. It was automatic and involuntary, a magnetic attraction drawing us in again and again. While the sub continued its descent, all five of us made several dives. This time, and in spite of the earlier symptoms, there was no trepidation, no hesitancy at all.

It was exhilarating. I have no words for what I saw and what I felt as I descended, exploring the upper level of the sub’s journey, the sunlight layer above the oval vent. I was not afraid. I pulled the full bodysuit over me, tipped backwards from the stern, and swept through the bright water for as long as my oxygen allowed. Afterwards I lay out on the deck, chest inflating and deflating rapidly, images spinning through my head. Waiting out the period until the next dive I towelled up and went indoors, back to the theatre, which, under Amy’s direction, was continuing to beam near-live footage from Scintilla’s journey beneath us.

To begin with, we couldn’t see anything. The sub kept getting stuck, tangled in free-floating weeds. But it was trained for this, and Amy cheered like a proud parent as it freed itself. Even by mid-range in the sunlight level the water was opaque. Scintilla adjusted its lighting, and the whole theatre flickered. I was getting impatient, and decided to go out for some air again, watch the water from the deck, where a little group had formed. Though we couldn’t see anything from here – the sub was hundreds of metres down already – it was satisfying to look on. For this – the fourth launch, the one that aimed for Hades – all non-essential ship work was suspended, and the atmosphere on deck was optimistic, collegiate, with just that hint of tension surviving from earlier.

Martin MacInnes

© Gary DoakGoing into the water was in the first instance an escape, and maybe in some sense it still was. Maybe what I thought was an objective and impersonal interest in the origin and development of cellular life was in fact something smaller, an attempt to flee my own history but also an acceptably disguised way of exploring it

While the water continued to pull me in, I was drawn, equally involuntarily, to my past. I returned to the ocean, as I returned to my childhood in Rotterdam, to Geert’s inexplicable beatings and to the nights following when Fenna mended me, kneaded me, and ushered me back as best she could. I looked back on the events as if they’d happened to another person, pitying this character as I would a stranger. But if she was a stranger, she’d still shaped the person I’d become. I didn’t want to think about this connection to her, didn’t want to admit it, sitting out on my towel in the sunshine.

I resisted being so easily explained, but I couldn’t help suspecting there was something in it. I wanted desperately for my life to be my own creation, to not have my present behaviour reduced to things that happened when I was young. My swims in the Nieuwe Maas were a reaction to Geert’s beatings and the site where I first discovered hope. Going into the water was in the first instance an escape, and maybe in some sense it still was. Maybe what I thought was an objective and impersonal interest in the origin and development of cellular life was in fact something smaller, an attempt to flee my own history but also an acceptably disguised way of exploring it. Maybe, rather than investigating the origins of life, I was merely and regrettably pursuing my own individual history. While I opened my eyes and with difficulty raised myself on deck, gazing out again into the ultramarine, fierce sunlight bouncing off the blue, I recalled the life forms I studied, further insight into which I believed existed in the vent below us now, the same organisms that populated and substantiated the pain I felt as a child. They were, in a sense, the physical constituents accompanying and embodying that earlier drama, my nine-year-old self hugging her cramping stomach the day after a beating. But they were more than that – their purpose was infinitely variable, they were the source, I thought, of joy and exhilaration as much as they were terror, pain. They were the source of everything, inside us and beyond us, before us and long after we were succeeded. While I studied it, I had to admit I was entangled in it too. It couldn’t be otherwise – I came from it. And as part of this honesty I might have to face that my mind – my ‘character’, as I might call it, which I still willed in some naive way as my own creation, an infinitely regressive loop – was not separate and cut off either. Entangled in its thicket, I looked into the water with eyes that were born there, several billion years before. This challenged me, reduced me and provoked me, but it also instilled in me a desire to keep going, to keep pushing, to continue this exploration just as far as I could take it, across the remainder of my conscious days.

We huddled in the theatre again, watching the spectral, loamy greys and whites of the sub’s beam as it crawled through the midnight layer. My mind was full of fractal sponges and long, leaf-like creatures built completely from repetition, self-similar organisms stating themselves again and again, the creatures of the Avalon period, the original radiation of multicellular life. But in reality, I saw little. Anything we observed here – anything living; and Ursula, an expert on cetaceans, believed large vertebrates may well exist here – fed primarily on extremophile archaea and the filtered organic fog of bodies torn apart at the sunlight heights. The sub swivelled just a little and the white wash of its beam through the outer darkness illuminated an inestimable distance – 2 metres or 200 metres, laterally – and I saw glimpses of tiny particulate matter, microcosms of a formerly coherent whole, the spray of a body, which fed this dark life here and below the midnight layer too, the twilight and the hadal – and even the sub-hadal, the below-underworld, should such a place exist. The generosity of porous life, I thought, watching what I believed was the disintegrated water-torn body of something that had lived, had sensed, had felt, had possessed its own wishes. Death begetting life. I was moved by this, stupidly; the sacrifice of everything that lived, everything that turned to mist. Silica mats descending and giving rise to the same conditions that created the sea vent. Diatoms and coccoliths’ skeletons and shells sinking to the last, building up beds of chalk and limestone across billions of years. The silent weather of a body, pushing onto the ocean and the atmosphere, sustaining new life, continued life, bringing—

Everything stopped. Everything went dead. ‘Fuck!’ Amy shouted. The feed cut to absolute black as the theatre, in turn, was plunged into invisibility. Pockets of blue light shone from phones, people murmuring; someone found a switch. Not an electrical problem – power continued to run through the ship. Not a local problem on the projector either. So it was the sub itself, Scintilla – the feed had gone, still only descending through the upper regions of the midnight layer.

We played the recorded images back, as if attempting to pretend it wasn’t true. Felix and I went to the kitchen and put out a spread. Food helped. There was a lot of confusion in the hours that followed; rumours, attempts at clarification, conflicting information, all driven by the absence of any clear statement from Stefan, Amy and the team, locked in the control room. The most dramatic rumour was that something had struck the sub, shattering the camera lens – protected behind reinforced plexiglass – and compromised the whole structure. Some said the mission was over, we had no choice but to abort it. This idea, of going back, was devastating; I wasn’t prepared for it. Others said it was only visual contact that was lost, and while this was a huge blow, it didn’t affect our goal of charting the vent’s absolute depth. In the early evening Stefan called us back and announced, in the theatre, that until we had established exactly what had happened, no further dives would be permitted.

In Ascension by Martin MacInnes