Reading list

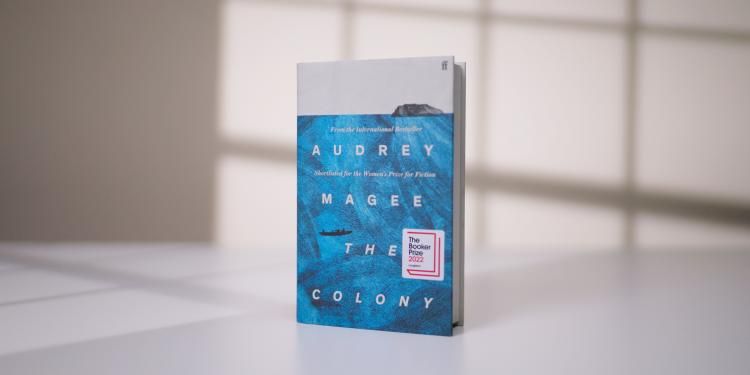

In Audrey Magee’s lyrical and brooding fable, two outsiders visit a small island off the west coast of Ireland, with unforeseen and haunting consequences. Read the opening chapter here

Mr Lloyd has decided to travel to the island by boat without engine - the authentic experience. Mr Masson will also soon be arriving for the summer. Both Englishman and Frenchman will strive to encapsulate the truth of this place - one in his paintings, the other with his faithful rendition of its speech, the language he hopes to preserve.

But the people who live on this rock - three miles wide and half a mile long - have their own views on what is being recorded, what is being taken and what is given in return. At the end of the summer, as the visitors head home, there will be a reckoning.

Read more extracts from this year’s longlisted titles here.

Read an interview with Audrey Magee here.

He handed the easel to the boatman, reaching down the pier wall towards the sea.

Have you got it?

I do, Mr Lloyd.

His brushes and paints were in a mahogany chest wrapped in layers of thick, white plastic. He carried the chest to the edge of the pier.

This one is heavy, he said.

It’ll be grand, Mr Lloyd. Pass it down.

He knelt on the concrete and slid the chest down the wall towards the boatman, the white plastic slipping under his fingers.

I can’t hold it, he said.

Let it go, Mr Lloyd.

He sat on his heels and watched the boatman tuck the chest and easel under the seat near the prow, binding each to the other with lurid blue string.

Are they secure?

They’re grand, Mr Lloyd.

I hope they’re secure.

As I said, they’re grand.

He stood up and brushed the dust and dirt from his trousers. The boatman lifted his arm, offering his hand.

Just yourself then, Mr Lloyd, sir.

Lloyd nodded. He handed his canvas pack to the boatman and stepped cautiously onto the ladder set into the crumbling pier.

Turn around, Mr Lloyd. Your back to me.

He looked down, at the small boat, at the sea. He hesitated. Stalled.

You’ll be grand, Mr Lloyd.

He turned and dropped his right leg to search for the first step beneath him, his hands gripping the rusting metal as his leg dangled, his eyes shut tight, against the possibilities

of catching skin

cutting fingers

blemishing hands

of slipping

on steps

coated in seaweed and slime

of falling

falling into the sea

The step is under you, Mr Lloyd.

I can’t find it.

Relax your knee, Mr Lloyd. Reach.

I can’t.

You’ll be grand.

He dropped his knee and found the step. He paused, gripping still to the ladder.

Only two steps left, Mr Lloyd.

He moved his hands down the ladder, then his legs. He stopped on the third step. He looked down, at the gap between his feet and the low-lying boat.

It’s too far.

Just reach with your leg, Mr Lloyd.

Lloyd shook his head, his body. He looked down again, at his backpack, his easel, his chest of paints bound already to the journey across the sea in a handmade boat. He dropped his right leg, then his left, but clung still to the ladder.

self-portrait I: falling

self-portrait II: drowning

self-portrait III: disappearing

self-portrait IV: under the water

self-portrait V: the disappeared

Audrey Magee

© Jonathan HessionLloyd sighed. He closed his eyes and lifted his face to the sun, surprised by its warmth when he had expected only northern cold, northern rain.

Well done to Audrey Magee for being longlisted for the #BookerPrize2022 with ‘The Colony’.@FaberBooks https://t.co/4mUmDIuqRP pic.twitter.com/TK4JEOUxz6

— The Booker Prizes (@TheBookerPrizes) July 26, 2022

Let go, Mr Lloyd.

I can’t.

You’ll be grand.

He crashed into the boat, tipping it to one side, soaking his trousers, his boots and socks, water seeping between his toes as the boatman pumped his right leg against the swirl of sea splashing over the top of the boat, his leg feverish until the currach was again balanced. The boatman bent forward, to rest on his knees. He was panting.

My feet are wet.

You’re lucky it’s only your feet, Mr Lloyd.

The boatman pointed at the stern.

Go and sit down, Mr Lloyd.

But my feet are wet.

The boatman stilled his breath.

That’s boats for you, Mr Lloyd.

Lloyd shuffed towards the back of the boat, hanging from the boatman’s callused hands as he turned to sit on a narrow, splintered plank.

I hate wet feet, he said.

He reached his hands towards the boatman.

I’ll take my backpack now. Thank you.

The boatman handed him his pack and Lloyd placed it on his knees, away from the water sloshing still about the bottom of the boat.

I won’t object if you change your mind, Mr Lloyd. And I’ll not charge you. Not all of it, anyway.

I’ll carry on as planned, thank you.

It’s not common any more. To cross like this.

I’m aware of that.

And it can be a hard crossing.

I’ve read that.

Harder than anywhere else.

Thank you. I’ll be fine.

He closed the buttons of his waxed coat and pulled on his new tweed cap, its green and brown tones blending with the rest of his clothing.

self-portrait: preparing for the sea crossing

He reached down his legs and flicked the beaded water from his trousers, from his socks, from the laces of his boots.

Will you be staying long, Mr Lloyd?

For the summer.

That’ll do you.

Lloyd straightened the pack on his lap.

I’m ready, he said.

Grand.

Shouldn’t we go?

Soon enough.

How long?

Not long.

But we’re missing all the daylight.

The boatman laughed.

It’s June, Mr Lloyd.

And?

Plenty of light left in that sky.

What’s the forecast?

The boatman looked at the sky.

Calm day, thank God.

But that could change.

It could, Mr Lloyd.

Will it?

Oh, it will, Mr Lloyd.

So we should go now. Before it changes.

Not yet, Mr Lloyd.

Lloyd sighed. He closed his eyes and lifted his face to the sun, surprised by its warmth when he had expected only northern cold, northern rain. He absorbed the heat for some minutes, and opened his eyes again. The boatman was standing as he had been, looking towards land, his body shifting with the rhythm of the water that lapped gently against the pier wall.

Lloyd sighed again.

I really think we should go, he said.

Not yet, Mr Lloyd.

I am very keen to get there. To settle in.

It’s early yet, Mr Lloyd.

The boatman reached into the inside of his jacket and took out a cigarette. He detached the filter and flicked it into the sea.

A fish might eat that, said Lloyd.

It might.

That’s not good for the fish.

The boatman shrugged.

It’ll be more careful next time.

Lloyd closed his eyes, but opened them again.

I want to leave, he said.

Not yet, Mr Lloyd.

I have paid you a lot of money, he said.

Indeed you have, Mr Lloyd, and I appreciate it.

And I’d like to go now.

I understand that.

So let’s go.

As I said, not yet, Mr Lloyd.

Why ever not? I’m ready.

The boatman drew deeply on the cigarette. Lloyd sighed, blowing through his lips, and poked at the boat, sticking his heels and fingers into the wooden frame coated with canvas and tar.

Did you build it? said Lloyd.

I did.

Did it take long?

It did.

How long?

Long enough.

self-portrait: conversation with the boatman

He pulled a small sketchpad and pencil from a side pocket on his pack. He turned to a blank sheet and began to draw the pier, stubby and inelegant but encrusted with barnacles and seaweed that glistened in the sunshine, the shells and fronds still wet from the morning tide. He drew the rope leading from the pier to the boat and was starting on the frame of the currach when the boatman spoke.

Here he is. The man himself.

Lloyd looked up.

Who?

Francis Gillan.

Who’s he?

The boatman tossed the last of his cigarette into the sea. He cupped his hands and blew into his palms, rubbing each into the other.

It’s a long way, Mr Lloyd.

And?

I can’t row it on my own.

You should have said.

I just did, Mr Lloyd.

Francis dropped from the ladder into the currach, landing lightly on the floor of the boat, his movements barely rippling the water.

Lloyd sighed

balletic

poised

movements unlike mine

He nodded at Francis.

Hello, he said.

Francis tugged the rope from the ring in the wall.

Dia is Muire dhuit, he said.

The first boatman laughed.

No English from him, he said. Not this morning, anyway.

The boatmen lifted long, skinny sticks, one in each hand.

We’ll go now, said the boatman.

We are so thrilled that Audrey Magee’s The Colony and Small Things Like These by @CKeeganFiction are on the #BookerPrize2022 longlist.

— Faber Books (@FaberBooks) July 26, 2022

Here is what the judges had to say about these two incredible novels: pic.twitter.com/r4mEcslXPE

They left the harbour, passing rocks blackened and washed smooth by waves, gulls resting on the stagnant surface, staring as they rowed past.

Lloyd returned his sketchpad and pencil to their pocket.

At last, he said.

The boatmen dropped the sticks into the water.

Are they oars?

They are indeed, Mr Lloyd.

They have no blades. No paddles.

Some do. Some don’t.

Don’t you need them?

If we get there, we don’t.

The men pushed against the wall and Lloyd gripped the sides of the boat, digging his fingers into the canvas and tar, into the coarse fragility of a homemade boat as it headed out into the Atlantic Ocean, into the strangeness, the unfamiliar

the not

willowed rivers

coxswains’ callings

muscled shoulders, tanned skin

sunglasses, caps and counting

not that

the familiar

no

They moved towards the harbour mouth, past small trawlers and rowing boats with outboard engines. The boatman pointed at a vessel that was smaller than the trawlers but larger than the currach.

That’s the one that’ll bring your bags, he said.

Lloyd nodded.

It’s how the other visitors come across.

Are there many visitors?

No.

That’s good.

You’d be better off on that boat, Mr Lloyd.

Lloyd closed his eyes, shutting out the boatman. He opened them again.

I’m happy in this one.

The big one is safer, Mr Lloyd. It has an engine and sails.

I’ll be fine.

Right so, Mr Lloyd, sir.

They left the harbour, passing rocks blackened and washed smooth by waves, gulls resting on the stagnant surface, staring as they rowed past.

self-portrait: with gulls and rocks

self-portrait: with boatmen, gulls and rocks

How long will it take?

Three, four hours. It depends.

It’s ten miles, isn’t it?

Nine. That other boat of mine takes a bit more than an hour.

I like this boat. It’s closer to the sea.

The boatman pulled on the oars.

It’s that all right.

Lloyd leaned to one side and dropped his hand into the sea, spreading his fingers to harrow the water.

self-portrait: becoming an island man

self-portrait: going native

He wiped his chilled hand over his trousers. He lifted his pack and laid it behind him.

That’s risky, said the boatman.

It’ll be fine, said Lloyd.

He leaned against the pack and moved his fingers as though drawing the boatmen while they rowed

small men

slight men

hips, shoulders, backs

flowing

over anchored legs

Your boat is a different shape to the pictures in my book.

Different boats for different parts, Mr Lloyd.

This one looks deeper.

Deeper boats for deeper waters. The shallow boats are grand for islands that are close in.

Not this one?

No, too far.

Is it safe?

This boat?

Yes.

The boatman shrugged.

It’s a bit late to be asking.

Lloyd laughed.

I suppose it is.

self-portrait: going native with the island men

The Colony by Audrey Magee is published by Faber, £14.99

The Colony by Audrey Magee