Sara Collins on Andrea Levy: She changed our minds about history

Author Sara Collins reflects on Andrea Levy’s unparalleled ability to write about Jamaica’s colonial history, with her signature dash of levity

Andrea Levy’s 2010 bittersweet novel about the last days of slavery in Jamaica is powerful and intimate – and full of mischievous surprise. Read an extract from our June Book of the Month here

Set during the turbulent years of slavery and the early years of freedom that followed, The Long Song is a thrilling journey through that time in the company of people who lived it. Based on the lives of the people who live and work on the Amity sugar plantation, the narrative centres around July, a slave girl with an indomitable spirit for survival.

The Long Song was shortlisted for the Booker Prize in 2010 and is published in the UK by Tinder Press.

SO, READER, KITTY’S ONLY child is born in upon the world at last. Kitty called her daughter July, for when she was still a callow girl, Miss Martha, who did oversee the infant workers of the third gang, had once ventured to teach Kitty to write in words the months that make up the year. Although the month of her pickney’s birth was December, it was only the graceful wave of Miss Martha’s arm as she scratched the flowing curls of the word July in the dirt that the older Kitty could call to mind. Kitty softly whispered the word July into her pickney’s ear and July her daughter became.

And what a squealing, tempestuous, fuss-making child she was. The quivering pink tongue and toothless gums in July’s shrieking mouth were more familiar to her mama than her baby’s arms and feet. With such agitation coming hourly from this newly born creature, Kitty did believe that this pickney must have been ripped from some more charmed existence. That she howled for the injustice that found her now a slave in an airless hut, in a crib too small, and being mothered by an ugly-skinned black woman who did not have the faintest notion as to why her pickney did yell so.

Kitty paced her tiny hut for most of the hours in the night to try to bring peace to this cursed child’s heart. Then, when the child was calmed enough for Kitty’s eyelids to at last close in sleep, the driver blowing a shrill note upon the conch bade her open them once more for another day of work. Only when Kitty was ready to feed this baby, so her working day could commence, did this child decide the time was right to sleep like the dead. And only after she had wrapped the sleeping child to her back and begun her work on the second gang—clearing and carrying the bundles of spent cane from the factory to the trash house—did Kitty feel the gentle swelling of her pickney’s lungs as July awakened to demand her missing food.

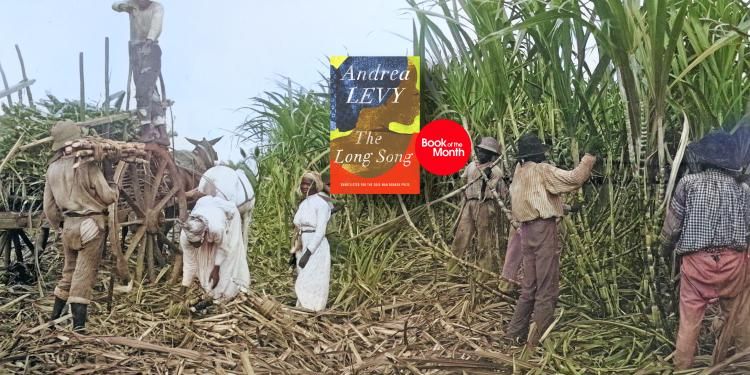

Workers in sugar cane fields in the Caribbean, circa 1890 [digitally colorized]

© Archive Farms/Getty ImagesOh, pity poor Kitty, for no sound so vexed the negroes that worked around her than the constant screeching of the child that was bound to her throughout the day. All in her second gang agreed that not even the shrill creaking of the carts that carried the cane from the fields to the mill—yes, even the broken-down one that Cornet Jump did drive—did pain them so much.

The call of the driver, Mason Jackson, as he summoned luckless slaves to unload that heaping cane from the carts was piercing—true—but it did not rupture the ears like that pickney. And the groaning sighs that always exhaled from Miss Anne and Miss Betsy as their sore heads were piled up high with the spiky bundles of cane, rang quite soft inc comparison. As did their slip-slop shuffling as they humped the weeping poles to where they would be crushed.

The rasping of the wooden cattle mill as it laggardly turned and the weary clip-clopping of the beasts’ hooves as Benjamin Brown guided them to tread their pointless progress around and around, never again seemed quite so loud to him. Even the squelching of the cloying juice being squeezed from the splitting poles or the raucous jabber of Miss Bessy and Miss Sarah as they reaped the spent cane from the floor about him, did not play so sharply upon his nerves.

And Dublin Hilton, the distiller-man (him who did know if the liquor would granulate from just gazing upon it or inhaling the vapour), will tell you that not even the crackling of the flames under his coppers, the bubbling slurp of the boiling sugar, nor the deep rumbling from the hogsheads as the filled barrels were rolled along the ground, could keep that pickney’s howl from finding his ears.

The Long Song by Andrea Levy

Kitty paced her tiny hut for most of the hours in the night to try to bring peace to this cursed child’s heart. Then, when the child was calmed enough for Kitty’s eyelids to at last close in sleep, the driver blowing a shrill note upon the conch bade her open them once more for another day of work.

Come, only the firing of the driver’s cowskin whip, as he directed which to be taken where, did all within that second gang confess, was more vexing to them than the torturous din that emitted from the tiny creature tied to Miss Kitty’s back. ‘A likkle rum ’pon the child’s tongue, Miss Kitty,’ Peggy Jump, from the first gang, did yell from her door at the close of each day. While, ‘Shake the pickney soft!’ was Elizabeth Millar’s suggestion and, ‘See, Obeah—she mus’ haf a likkle spell,’ was the thinking of Kitty’s friend, Miss Fanny.

But what Kitty’s neighbours did not observe was that sometimes, late into the still of night, Kitty could calm July by singing a song soft unto her. ‘Mama gon’ rock, mama gon’ hold, little girl-child mine.’ Then July would turn her black eyes on to Kitty, her lips gently mimicking the movement of her mama’s mouth as she sang. That beguiled child would then hug Kitty—her little arms squeezing about her neck while she fondly dribbled tender wet kisses upon her mama.

Kitty would bounce her precious girl-child upon her knee and July would chuckle with an unbounded mirth that chirped as bright as fledglings in a nest. At those times there was no slapping, no cussing, no cursing, for July would gaze upon her mama with so deep an expression of love that Kitty felt it as heat. ‘Mama gon’ rock, mama gon’ hold, little girlchild mine.’ Sometimes, within this fond reverie, all was good. Until, that is, Kitty did venture to lay July back down upon her crib to sleep, for then that rascal child’s mouth would suddenly gape wide as a hole made for cane, as she began her yelling once more.

Excerpted from The Long Song by Andrea Levy. Copyright © 2010. Excerpted by permission of Headline Publishing Group. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Sugar cane cutters, Jamaica, circa 1905

© Print Collector/Getty Images