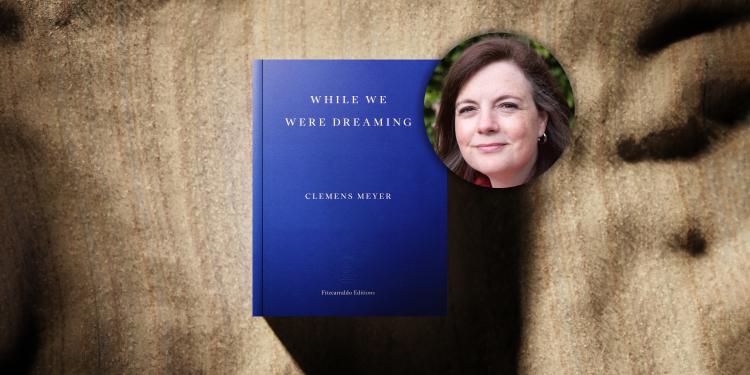

Clemens Meyer interview: 'I had to find the right style – rough but romantic'

Longlisted for the International Booker Prize 2023, author Clemens Meyer talks about While We Were Dreaming in an exclusive interview

With While We Were Dreaming longlisted for the International Booker Prize 2023, its translator talks about how the book has haunted her since 2006 – and calling on her fellow word nerds for support

Read interviews with all of the longlisted authors and translators here.

How does it feel to be longlisted for the International Booker Prize 2023 – an award which recognises the art of translation in such a way that the translators and author share the prize money equally should they win – and what would winning the prize mean to you?

It feels amazing! It feels like an acknowledgement of the love and effort we translators put into our work, and I hope it gets more attention for all the nominated books. Translated fiction can struggle for space in the UK’s crowded market, partly because the writers aren’t usually on the ground to do signings, events and so on. So shining a light on these thirteen titles is invaluable – and for me, it confirms my belief in Clemens Meyer’s incredible novel While We Were Dreaming. Plus it’s five literary experts saying: Yes, Katy, you are pretty good at your job.

How long did it take to translate the book, and what does your working process look like? Do you read the book multiple times first? Do you translate it in the order it’s written?

Although the novel is Clemens’ debut, it’s the fourth of his books that I’ve translated. I think the translation itself took about six to eight months, but because the book itself has been haunting me since it first came out in 2006, the process feels much longer – like the previous three translations were laying the ground for this one over the years.

I’m not sure how many times I’ve read the book now but I definitely took a good long wallow in it immediately before I sat down to translate the whole thing. And then, yes, I start at the beginning and work through to the end. One idiosyncrasy, I suppose, is that I always read back the previous day’s work before I move on to translating – that way I feel like I’m immersing myself in the tone again, and I hope also catching any booboos, killing yesterday’s spur-of-the-moment darlings.

I also workshop parts of my translation at our monthly translation lab in Berlin: a group of very supportive fellow word nerds who are happy to say: Katy, that doesn’t work for me, but what if you did it like this…? And then there are a couple more read-throughs, edits, and so on.

I’ve written more about the process in a translation journal for the Toledo Programme in Berlin.

What was the experience of working with Clemens Meyer like? How closely did you work together? Was it a very collaborative process? Were there any surprising moments during your collaboration, or joyful moments, or challenges?

Our collaboration isn’t necessarily on the page, as such. Over the years, Clemens and I have spent time together in Edinburgh, Berlin, London and his home town of Leipzig, where the novel is set. Sometimes doing events together and sometimes just hanging out. A couple of years ago, he showed me and his Italian translator Roberta Gado around some of the settings for his short-story collection Dark Satellites, also largely in Leipzig. So we saw the outsides and insides of a few pubs, a burger bar with a carpet, a particular wall alongside the railway tracks… I think what we’ve built is a kind of trust that means Clemens doesn’t worry too much about my translation. Obviously, I send him an email or a text message if I have questions. And sometimes I really want songs or characters’ names to resonate with an Anglophone readership, and I’ll ask Clemens if it’s OK to change them. Sometimes he says yes, sometimes he says no.

Katy Derbyshire

© Nane DiehlIf Jamaican musicians hadn’t melded New Orleans-style rhythm & blues with mento and calypso, we wouldn’t have reggae and all its many offshoots. Translated fiction helps that cross-pollination to come about, helps keep literature vibrant

Aside from the book, what other writing did you draw inspiration from for your translation?

You know, in this case the book itself stood alone, perhaps because I now know Clemens’s work so well. For previous translations I’ve read Hemingway short stories, sex workers’ writing, a gangster memoir, e.e. cummings, Grimms’ fairy tales, David Peace, Wolfgang Hilbig translated by Isabel Cole, and I think parts of the Qur’an. For While We Were Dreaming, I did try watching Top Boy to get a feeling for how teenage boys talk, especially about drugs – but it felt too much of its own time and place. It wouldn’t make sense for boys in 1990s Leipzig to sound like Dushane and Sully.

What was your path to becoming a translator of literary fiction? What would you say to someone who is considering such a career for themselves?

I started translating non-literary stuff because it was one of the few steady jobs I could do in Berlin without German qualifications, back in the late ’90s. So I was earning a living and enjoying the mechanics of translation, but not necessarily the material. As my German got more sophisticated I discovered more and more books I wanted English-speakers to be able to read – I became a real evangelist! But from there to actually getting literary translations published was a leap. I didn’t have any connections to UK publishing at all. The turning point was twofold: A German publisher recommended me to a British house (the great Anthea Bell was busy) and I attended the British Centre for Literary Translation’s summer school, where I met some amazing people, including Stefan Tobler, who later set up And Other Stories and published my first translation of Clemens Meyer, the collection All the Lights. It took me a long time to say out loud that I wanted to translate literature, and a lot of sample translations, submissions to journals, organising of events and general graft to get there.

If you’re considering it, I’d say: make sure you have a day job, work on writing you love, spend time in the country or countries of your source language, try and cultivate a thick skin but keep on keeping on. And read, read, read, in both languages!

Why do you feel it’s important for us to celebrate translated fiction?

I don’t think translated fiction has any inherent value that un-translated fiction doesn’t have; reading it won’t make us better people or necessarily teach us anything about its settings. But if we’re celebrating fiction, why should we limit ourselves to work created only in one language? Why restrict our horizons when there’s a whole world out there? I like to imagine translation enabling a criss-crossing of ideas between writers and readers – and writers and other writers – around the globe. Perhaps the best comparison might be music: put simply, if Jamaican musicians hadn’t melded New Orleans-style rhythm & blues with mento and calypso (themselves composed of many influences), we wouldn’t have reggae and all its many offshoots. Translated fiction helps that cross-pollination to come about, helps keep literature vibrant.

If you had to choose three works of fiction that have inspired your career the most, what would they be and why?

Conrad the Factory-Made Boy by Christine Nöstlinger, translated by Anthea Bell, is the first translated book I remember reading, in class at middle school. It’s an anarchic tale of a perfect boy wrongly delivered in a tin can to a chaotic single woman, and aside from not quite understanding the layout of their block of flats, it seemed like a perfectly normal – if wildly outrageous – book at the time. I assume I didn’t even know it was translated, or indeed set in Austria. But it certainly enriched my childhood reading, and my son loved it later on. I’d say that experience taught me that translated fiction isn’t necessarily exotic.

I love Breon Mitchell’s 2009 retranslation of The Tin Drum, Günter Grass’s classic. It’s so exuberantly done, really embracing the possibilities the English language grants us. Even the first page features gorgeous words such as cartilaginous, impales, manifold… and the rhythm is deeply satisfying, with one paragraph ending ‘and drops his polychrome plans’. To me, it’s an example of how deep respect for a book doesn’t necessarily mean opting for the most obvious translation – Mitchell celebrates the narrator’s tone in each of his choices. It has been genuinely inspiring.

The most recent work of fiction to inspire me, career-wise, is Jen Calleja’s Vehicle. The author translates from German, writes poetry and prose, runs a small press and is also a musician. Her novel is great feminist fun, part let’s-get-the-band-back-together roadtrip, part a Scooby-gang of rogue researchers in a dystopian future, part experimental narrative. I’m reading it for the second time right now and it’s seeping into my dreams. The book centres translation as a creative act of rebellion – against a closed and conservative society, and also against personal isolation. What could be more inspiring for a literary translator?

Clemens Meyer