Katy Derbyshire interview: 'Respect for a book doesn’t mean opting for an obvious translation'

Longlisted for the International Booker Prize 2023, translator Katy Derbyshire talks about While We Were Dreaming in an exclusive interview

With While We Were Dreaming longlisted for the International Booker Prize 2023, its author talks about searching for his debut novel’s theme – and writing on an old typewriter

Read interviews with all of the longlisted authors and translators here.

How does it feel to be longlisted for the International Booker Prize 2023, and what would winning mean to you?

It’s an honour, and after all these years of writing, a wonderful recognition and appreciation that means a lot to me.

What were the inspirations behind While We Were Dreaming? What made you want to tell this particular story?

When I was on the path to becoming a writer, an author, I was searching for my first theme, my first subject, and I suddenly realised that those stormy times after and before the fall of the [Berlin] Wall – which I was a part of – could be transformed into a great tragedy, a great epic. All those figures, lost in time, struggling but still dreaming.

How long did it take to write While We Were Dreaming, and what does your writing process look like? Do you type or write in longhand? Are there multiple drafts or sudden bursts of activity? Is the plot and structure intricately mapped out in advance?

It took me six years. I had to find the right style for it – clear as glass but still poetic, rough but still romantic, fragmented but still epic – and then I had to compose all the episodes. For a long time, I was looking for the right form, for a way bring it all together, whether linear or non-linear… until one of my mentors told me: write a montage novel, like, among others, [John] Dos Passos. And I did. I wrote half of the novel with an old typewriter, but then I switched to a notebook, which made things easier, although typewriting did teach me a lot about the rhythm and precision of words and sentences.

Where do you write? What does your working space look like?

I live in a small flat, which is where I work – it’s full of books, films, art and music. It’s like a cave. To visitors (which are rare, besides my children or my girlfriend) it looks like complete chaos, but I know where every book, piece or scrap of paper is (almost!).

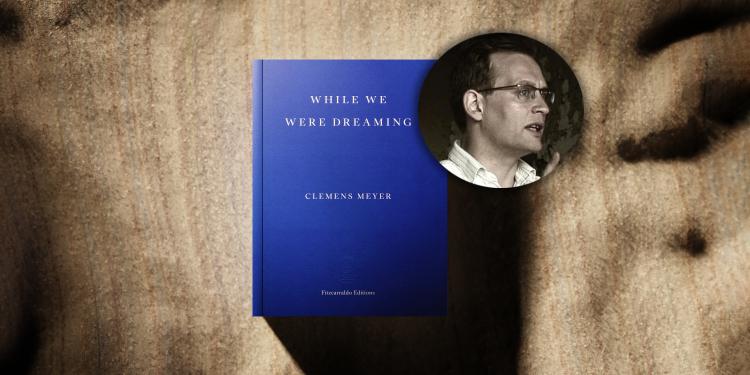

Clemens Meyer

I live in a small flat, which is where I work – it’s full of books, films, art and music. It’s like a cave. To visitors (which are rare, besides my children or my girlfriend) it looks like complete chaos

What was the experience of working with the book’s translator, Katy Derbyshire, like? How closely did you work together on the English edition? Did you offer any specific guidance or advice? Were there any surprising moments during your collaboration, or joyful moments, or challenges?

I completely trust Katy Derbyshire. She had already translated a few of my books and did a great job. Of course, she asked a lot of questions about some of the events in While We Were Dreaming, she wanted to know some background details, but it was a smooth process, she was in her element. We had some discussions over the title, but as my English is only intermediate, she had the final say. I’m thankful that the book is now available in English!

Why do you feel it’s important for us to celebrate translated fiction?

There is so much great literature around the world. Discovering new worlds via literature is important, discovering the immortal power of storytelling is important, discovering the magic of other languages is important, so we should celebrate translated fiction, always.

If you had to choose three works of fiction that have inspired your career the most, what would they be and why?

Manhattan Transfer by John Dos Passos. When I was reading it, around 1997, I thought, ‘Wow, that’s true modernism’. It was similar to [Alfred] Döblin’s Berlin Alexanderplatz, but more fragmented, more nervous, with all these shortcuts and cut-ups, the voices and influences of the big city. It was an overwhelming reading experience.

The Death Ship by B. Traven. Traven, who was German but moved to Mexico in 1918, wrote an unbelievably intense novel about a lost sailor with no passport, who travels across seas and oceans on board a so-called ‘death ship’, which is ultimately destined to sink because the owners want to cash the insurance. Expressionistic and modern, it brings together raw realism and epic mythology. It’s astonishing, especially when you remember it was written in the 1920s.

Franziska Linkerhand by Brigitte Reimann. I found myself falling in love with both the writer (although she died in 1973 at age 39) and the protagonist. It is the story of a young woman who is trying to change both the architecture of East German working-class prefabricated housing (or panel buildings), and the architecture of the contemporary models of love. Reimann’s prose has the same intensity of that of Faulkner or even Virginia Woolf, but inhabits its own socialistic realism, full of social critique, but also full of hopes and dreams. It’s completely hea

Katy Derbyshire

© Nane Diehl