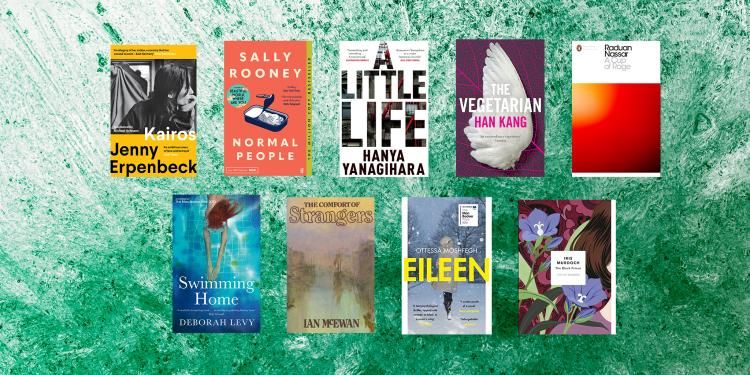

10 of the most heartbreaking books from the Booker Library

Sometimes we all need a book that will give us a good cry. These deeply emotional novels from the Booker Prize archives will break your heart – and mend it again

Inspired by this year’s International Booker Prize-winning novel, we’ve curated a selection of reads from the Booker Library that explore the darker depths of human interactions

Complex relationships lie at the heart of many great fictional reads, and toxic dynamics are no exception. Great literature has the unique ability to pull back the curtain on the darker elements of human nature, and expose the cruelty and manipulation at the heart of relationships between couples, friends and relatives.

This year’s International Booker Prize winner, Kairos by Jenny Erpenbeck, translated by Michael Hofman, is one such book – which presents the intimate and devastating story of an age-gap affair in terminal decline. ‘How can something that seems right in the beginning, turn into something wrong?’ Erpenbeck said in a recent interview with the Booker Prizes website, revealing her inspiration behind the novel – it was this ‘transition’ that interested her.

Deeply flawed relationships have captivated many authors within the Booker Prizes’ canon. So, to celebrate Kairos’s win, we have rummaged through the shelves to find other books that grapple with toxic bonds just as unflinchingly as the 2024 International Booker Prize winner.

Set against the backdrop of a divided Germany, this year’s International Booker Prize winner explores a doomed affair between a young woman and an older man in 1980s East Berlin. Katharina, a student, and Hans, a worldly retired academic, are drawn together through a chance encounter. Bound initially by shared passions for music and art, the couple gradually descend into manipulation and cruelty, yet neither is able to escape their situation.

Erpenbeck chooses not to shy away from uncomfortable moments, writing with a neutral lens about Hans and Katharina’s jealousy and sadomasochism, violence and cruelty. It’s a love story that offers parallels with the trajectory of the GDR – a country moving from idealism to self-destruction. Eleanor Wachtel, Chair of the International Booker Prize 2024 judges, said Kairos was ‘a devastating, even brutal love affair’. What makes it so unusual, Wachtel said, ‘is that it is both beautiful and uncomfortable, personal and political’. ‘Like the GDR, it starts with optimism and trust, then unravels.’

Sally Rooney’s bestselling novel, longlisted for the Booker Prize in 2018, captivated readers with its nuanced exploration of millennial love. Connell and Marianne’s tender, will-they-won’t-they relationship spans their school and university years. This is a coming-of-age story during which the pair remain in each other’s gravitational pull, despite distance and their individual struggles.

Both characters are damaged in different ways: Connell battles depression, while Marianne, who grew up surrounded by familial abuse and gendered violence, struggles with self-destruction and seeks validation through men. While studying in Sweden, she enters a troubling relationship with Lukas, a photographer, marked by a disturbing blend of dominance and submission. ‘Could he really do the gruesome things he does to her and believe at the same time that he’s acting out of love?’ Marianne asks, considering her escape. Rooney’s novel deftly portrays the complexities of relationships, including those that both heal and harm.

In 2015, Hanya Yanagihara’s A Little Life became a publishing sensation, evolving from a sleeper hit into one of the most buzzed-about titles of the year. Selling millions of copies and amassing a devoted online following, the novel’s success is all the more remarkable, given it is an often harrowing 700-page examination of deep trauma and enduring abuse.

Four graduates attempt to find their way in New York City, broke, adrift, and buoyed only by their friendship and ambition. Jude serves as their centre of gravity, a man whose shocking past shadows his present, trapping him in relentless cycles of suffering. In his early forties, Jude enters a profoundly abusive relationship after a meeting at a dinner party. Caleb’s disdain for Jude’s vulnerabilities manifests in physical and emotional cruelty, which Jude tolerates, believing he doesn’t deserve any better after a lifetime of abuse.

Despite being labeled as ‘torture porn’ by some critics, A Little Life continues to find new readers. Its unflinching portrayal of trauma and resilience ensures that it remains a powerful, if contentious, exploration of the limits of human endurance.

‘Before my wife turned vegetarian, I thought of her as completely unremarkable in every way,’ begins Han Kang’s The Vegetarian. The novel, told in three parts, offers a harrowing account of one woman’s decision to stop eating meat, and assert her bodily autonomy. Tellingly, the story is told through every viewpoint but her own.

Yeong-hye’s husband and family oppose her choice, while her seemingly simple act of rebellion unravels their control over her, exposing the deep-seated, societal violence embedded in their relationships. As a reading experience, the novel is profoundly unsettling: there are force feedings, violence, sexual assaults and institutionalism. Han Kang’s writing is concerned with the male gaze, and set in her native South Korea, The Vegetarian offers a searing feminist critique of the patriarchy and gendered violence.

In 2016, the novel became the first winner of the International Booker Prize after the award was restructured to mirror the English-language prize, presented annually for a single book.

In A Cup of Rage, Raduan Nassar crafts an explosive affair between an older man and a younger female journalist over the course of a single night in the Brazilian outback. Their relationship rapidly disintegrates into a vicious battle of wills and egos: ‘Our love was a kind of cannibalism; we fed on each other, consuming the flesh of our desires,’ Nassar writes.

Written in the 1970s by the reclusive Brazilian author Raduan Nassar and translated from Portuguese by Stefan Tobler 40 years later, the novel was longlisted for the International Booker Prize in 2016. Comprised of seven chapters which rattle along using unbroken sentences, the structure often demands careful reading; it builds in tension, often buckling under the weight of the tussle unfolding. The narrative is almost entirely dictated by the man’s internal monologue, transitioning from lust to fury, and rage to desperation. Expect vitriolic insults and warring egos – with a dash of eroticism – in this anxiety-ridden read.

An interloper exposes cracks in a marriage in Swimming Home, Deborah Levy’s family drama, which was shortlisted for the Booker Prize in 2012. Kitty Finch interrupts Joe and Isabel Barnes’ vacation on the French Riviera when she is found floating face down, but alive, in the swimming pool of their villa. Her arrival is anything but ordinary and as Kitty’s presence disrupts their tranquillity, Isabel’s decision to welcome her into their fold raises questions about her own motivations. Despite Joe’s history of infidelity, Isabel, a war correspondent, is far from a passive victim. Levy’s dreamlike prose, ethereal and hypnotic, hints at hidden agendas and unspoken desires. ‘Is it Kitty really who is wreaking chaos, or was it there anyway, in Isabel and Joe’s marriage?’ Levy asked, in a 2017 interview on BBC Radio 4 Bookclub. It’s up to the reader to find out.

A romantic European getaway takes a dark turn in The Comfort of Strangers, Ian McEwan’s chilling 1981 shortlisted novella, which follows a well-to-do English couple as they unintentionally become entangled with two locals with sinister intentions.

In the labyrinthine streets of Venice, Colin and Mary encounter Robert, a seedy bar owner, and his disabled wife, Caroline. As they are drawn into the couple’s orbit, it is clear all is not what it seems. There’s a twisted dynamic of pain and pleasure within their relationship and Caroline discloses Robert’s violent tendencies, which inflicted a lifelong injury on her: ‘It was not so much that he wanted to possess her, but rather that he wanted to take her to a place where no one else could ever follow’. A desire for dominance lies at the heart of McEwan’s eerie novel, with a narrative that threatens to throw readers off balance at every page-turn.

Ottessa Moshfegh’s debut full-length work thrust her into the spotlight when published in 2015. Set in the New England suburbs in December 1964, the novel follows the bleak existence of 24-year-old Eileen Dunlop. Trapped in a suffocating routine of caring for her verbally abusive, alcoholic father and her dead-end job at a juvenile correctional facility for troubled boys, Eileen yearns to escape. When the glamorous Rebecca Saint John arrives at the prison as a new counsellor, Eileen’s fascination quickly escalates into obsession. Yet, as their relationship deepens, it takes a sinister turn, leading Eileen down a path of shocking violence.

Moshfegh has a reputation for pushing boundaries and exploring the darker recesses of human nature through her writing, and she does just that and more here, while navigating an imbalance of power. The novel was shortlisted for the Booker Prize in 2016 and saw Moshfegh hailed as a ‘crucial’ voice in American literature by the LA Times.

By the time she wrote The Black Prince, Iris Murdoch had already been shortlisted for the Booker Prize twice, for The Nice and the Good in 1969, and Bruno’s Dream a year later.

Widely regarded as her best work, The Black Prince is part metafictional thriller, part love story, where ex-tax collector Bradley Pearson wishes to devote his retirement to writing ‘a masterpiece’. He’s a deeply unlikable man – pretentious, cruel, dismissive, and narcissistic. He is also determined to seduce Julian, his friend’s daughter, 30 years his junior. Preying on her naivety, Bradley whisks her away to a seaside cottage to evade her mother and father and the pair declare love. But their short-lived romance quickly unravels when Julian finds out Bradley’s real age, and he violently assaults her.

‘More than almost any other writer, [Murdoch] understands the currents beneath the surface: the way that inappropriate crushes, egotism, loathing, loneliness, can overcome apparently calm lives,’ wrote novelist Charlotte Mendelson, reviewing the book for the Guardian. Murdoch’s ability to explore the deep and often disturbing undercurrents of human behaviour in The Black Prince solidified her reputation as a masterful storyteller, and was shortlisted for the Booker Prize in 1973.