Book recommendations

Reading list

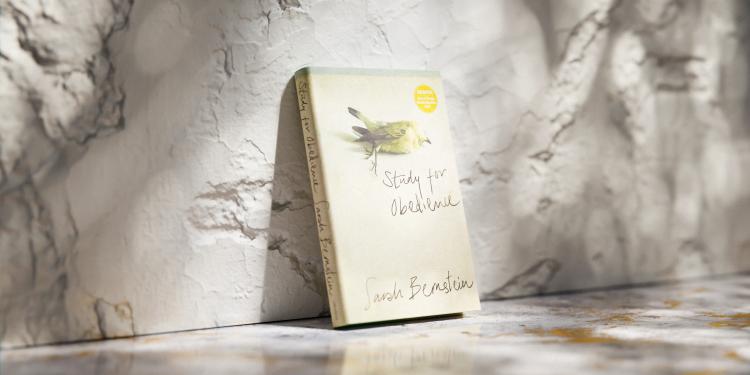

In her accomplished and unsettling second novel, Sarah Bernstein explores themes of prejudice, abuse and guilt through the eyes of a singularly unreliable narrator

A woman moves from the place of her birth to a ‘remote northern country’ to be housekeeper to her brother, whose wife has just left him. Soon after she arrives, a series of unfortunate events occurs: collective bovine hysteria; the death of a ewe and her nearly-born lamb; a local dog’s phantom pregnancy; a potato blight.

She notices that the community’s suspicion about incomers in general seems to be directed particularly in her case. She feels their hostility growing, pressing at the edges of her brother’s property. Inside the house, although she tends to her brother and his home with the utmost care and attention, he too begins to fall ill…

There was the house, standing at the end of a long dirt track and in a stand of trees, on a hill above a small, sparsely inhabited town. A creek marked the property boundary to one side, and at night the sound of its fretful flow came through my bedroom window. Looking down the long drive, one could see dense forest, a small town deep in the valley, and beyond, the mountains, higher than any I had seen before. The plot of land and the house which sat upon it belonged to my brother, my eldest brother. Why he ended up in this remote northern country, the country, it transpired, of our family’s ancestors, an obscure though reviled people who had been dogged across borders and put into pits, had doubtless to do, at least in part, with his sense of history, oriented as it was towards progress, turned towards the future, ever in search of efficiencies. From a practical point of view – and pragmatism was naturally of the utmost importance to my brother – he was also engaged in some perfectly reasonable, if slightly perverse, business dealings, for he was, or at least had been, a businessman involved in the successful selling and trading, importing and exporting, of a variety of goods and services, the specifics of which to this day remain a mystery to me.

I came to stay in the house upon his request and initially for a period of six months, leaving the country of our birth for this cold and faraway place where my brother had made his life, had at any rate made his money, of which there was, as I would come to see with my very own eyes, a great deal. I saw no reason to object – I had always wanted to live in the countryside, had often driven through the rural areas surrounding my natal city in the autumn to see the leaves in colour, to experience the fresh air, so different from the turgid air downtown, well known to be the primary cause of the high rates of infant mortality, not that I had children myself, no, no, nevertheless, the air quality and its deleterious effects on public health were of concern to me as much as they might have been to any other ordinary citizen. Moreover, as my brother pointed out, it was not as though I had any specific obligations or ties that could not be broken with ease. I allowed this. Here is how it was. I had so to speak thrown in the towel. My contemporaries had long surpassed me, had, whether by treachery or superior skill, secured their places in life and in their chosen professions. It was said that it was a terrible thing to realise a lifelong dream, and yet still I wondered why they could not let blood a bit. They bloated with success. There was so much time and nothing to be done. I had only a little bit of will. I was not in on the great joke. For a time I pursued a career as a journalist but eventually left the news agency at which I had been employed, not even in disgrace, my time there had run its course, there was nothing at all to mark my going. My efforts over the years to obtain a continuous contract of employment had been in vain, the process had been explained to me as a bureaucratic and not at all a personal one, and yet when I responded in kind, that is to say by invoking the usual bureaucratic processes and fully within my rights making a request according to the general data protection regulation guidelines under the suspicion something fishy was going on, the application was treated as a personal affront and it was made clear to me that I was not helping myself. In truth, I never had helped myself. I left quietly. No one was sorry to see me go. The job I held just prior to my departure to my brother’s home, in the country of our forebears, and which I would continue remotely from the same was as an audio typist for a legal firm, a job at which I excelled, typing quickly and accurately, knowing my work. Nevertheless, I sensed I was unwelcome in the office, which was lined with the usual legal appurtenances, binders and diplomas, leather and wood. I knew that my halting displays of personhood, my miserable insistence on continuing to appear in the office day after day, could only be disheartening to the jurists and paralegals whose voices I typed into a word processor swiftly, precisely, with devotion and even with love, and so they received my leaving announcement with unconcealed joy, throwing a farewell party in my honour, staging a kind of feast and donating lavish gifts. It did not take long for me to set my affairs in order, a matter of weeks, three months at the outside, and, the journey having passed without incident, here I was. The country air would be good for me, I felt, and the seclusion, when my brother did not need me I might take advantage of the various woodland paths maintained by local voluntary groups. I would be quiet.

Sarah Bernstein

© Alice MeikleAt the time of my arrival, my brother was not yet ailing. Truly he was in the very pink of health, the prime of his life; having recently freed himself from his wife and teenage children and their perennial demands, he was, he said, at last free to pursue his business ventures in peace

At the time of my arrival, my brother was not yet ailing. Truly he was in the very pink of health, the prime of his life; having recently freed himself from his wife and teenage children and their perennial demands, he was, he said, at last free to pursue his business ventures in peace. His investments had begun to pay off and, in the absence of his family, from whom he had, it transpired, long felt estranged, and since he spent a great deal of time away from his home, he found himself needing someone to look after the house, he told me one afternoon over the telephone. And who better than I, who from childhood had proven myself the most efficient, most doting manager of my siblings’ household affairs? When I did not respond immediately, he assured me that the house, although storied and ancient, although once belonging to the distinguished leaders of the historic crusade against our forebears, nevertheless had all the modern conveniences. These he enumerated, as though he were the agent of some new, dubious hotel: high-speed Internet, a variety of on-demand streaming services, a soaking tub, a rainfall shower, a memory foam mattress, hand-woven linens, a convection oven, a six-slice toaster, an ice machine, and so on and so forth. As my brother’s claims about the furnishings of his home proceeded by this logic of declension, it occurred to me as it had perhaps occurred to him that he knew very little about me and, what’s more, that this concerned him, the idea that he no longer knew what might please me. For instance, as he said the word ‘mattress’, his voice became suddenly panicked, as if he feared he had made the most irremediable blunder, that this mention of the mattress would be unacceptable, perhaps even offensive, to me. I was troubled by this sign of discontinuity in my brother’s total authority, it was clear to me that the business with his wife must have come as a blow to him, what little I knew of men suggested that they were constitutionally incapable of being alone, terrified of not being admired, and seemed to regard ageing and its effects as a personal failing. Yes, yes, I said. Of course I would come. Of course! I said, nearly shouting into the phone. When had I ever denied him, my eldest brother, or any of the succession of other siblings whose whereabouts were just then unknown to me, when had I ever denied any of them the smallest request? Of course I would come. Naturally, he said, recovering himself, he would arrange and pay for my journey, he would pick me up himself at the airport in his car, a new model he had only just acquired, and drive me back to the house. And he did do these things, he never reneged on promises or went back on his word, no matter how rashly given, no matter how intoxicated or coerced he had been at the moment of avowal, although it’s true in any case he gave his word freely and often, to friends and strangers alike, to business partners as well as adversaries, as far as my brother was concerned a thing, once said, was as good as done and that was all there was to it. When I exited the automatic doors of the airport, the navigation of which had taken me some time since the sensors did not at first register my movement, however exaggerated, so I had to wait until another recently deplaned passenger passed through the doors himself to exit, my brother’s car was already idling at the kerb. Through the window, he gestured to me to get in, and I did.

On the drive from the airport to his home, some two hours away, my brother admitted that his wife, in collusion with the children, had decamped to Lugano, where her people lived, without a word and so far as he could tell permanently and perhaps even in the dead of night. The match had been doomed from the start, my brother said as he drove through the rain, they had shared too much about themselves, knew too much about one another for mutual respect to be possible. What’s more, he went on, at various times, in alternating turns, they had committed the most grievous sins against one another, culminating finally in each speaking aloud the terrible truth of the other’s personality, truths they had long known about themselves and about one another, but about which they had come to a tacit agreement never to mention, never to discuss, never to give away the slightest hint that such knowledge existed. The wife, knowing the essential flaw in the husband’s heart, must never speak of it; likewise, the awful and indisputable fact of the wife’s character, this too must never be spoken by the husband. No, my brother said, not ever. Such was the basis of the marital relation. I opened the passenger-side window and the wet spring air blew in. I watched the passing landscape, the pale, incipient green of something left too long in the dark, I watched the sodden black branches as they passed, and then, yes, came the smell of spring. I felt a thrill run through me.

I recalled my own aborted attempts at intimacy, with men, with women, and all that I had ever come away with was a sense of my essential interchangeability. People touched me, when they touched me, with a series of predetermined gestures in no way adapted to

me, to my consciousness or sensations, limited though these were, insensible though I surely was. I had been so attentive to the particularities of their flesh, a smattering of freckles at the temple, bumps rising on the forearm, had cultivated this attention over time, painstakingly, aware of my inclination, congenital, towards vacancy, and yet this practice of contemplation never got me very far. My partners led me through the door, doing things to me they had done to others, doing things to me they could have done to anyone, anybody at all, and to put it plainly I was sure that, in each of their minds, with their eyes closed, they were with someone entirely other, not me – the tender kiss on the hairline, the holding of the back of the head, the grasping of the wrist, none of it was directed at me, all of it was for someone else, from before, some beloved, lost long ago. No, I thought, there was nothing I could say to my brother, no advice I could offer or consolation I could provide on the subject. All that was required, I felt, was one’s silence. Not to speak, not to say. That’s all.

Study for Obedience by Sarah Bernstein