Everything you need to know about the Booker Prize 2023 shortlist

As the Booker Prize 2023 shortlist is announced, we’ve pulled together the most interesting facts and trends that have emerged in this year’s selection

In her accomplished and unsettling second novel, Sarah Bernstein explores themes of prejudice, abuse and guilt through the eyes of a singularly unreliable narrator

Whether you’re new to the book or have read it and would like to explore it more deeply, here is our comprehensive guide, featuring insights from critics, our judges and the book’s author and translator, as well as discussion points and suggestions for further reading.

A woman moves from the place of her birth to a ‘remote northern country’ to be housekeeper to her brother, whose wife has just left him. Soon after she arrives, a series of unfortunate events occurs: collective bovine hysteria; the death of a ewe and her nearly-born lamb; a local dog’s phantom pregnancy; a potato blight.

She notices that the community’s suspicion about incomers in general seems to be directed particularly in her case. She feels their hostility growing, pressing at the edges of her brother’s property. Inside the house, although she tends to her brother and his home with the utmost care and attention, he too begins to fall ill…

Narrator

The lead character, who is not named, is the youngest female sibling in a large family that has always treated her like a servant. She has spent her whole life being put-upon and exploited, existing only to tend to the needs of others. She goes to be her eldest brother’s housekeeper in a house outside a small town in an unnamed country where she doesn’t speak the language. After her brother leaves on business, the townspeople appear to hold the narrator responsible for various disturbing natural occurrences. The entire book is presented from her point of view and while we see the locals’ fear and distrust of her, despite her misguided attempts to forge a connection with them, we are left to guess at the reality of her effect on others, and what exactly leaves everyone she encounters feeling so troubled.

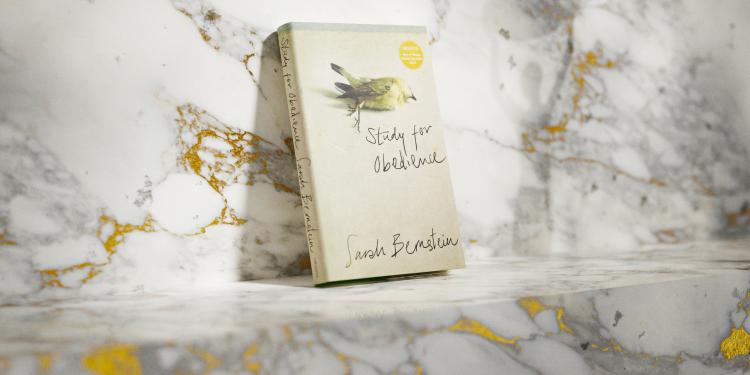

Study for Obedience by Sarah Bernstein

Sarah Bernstein is a Canadian writer and scholar who was born in Montreal and now lives in the Scottish Highlands, where she teaches literature and creative writing. In 2015, she published Now Comes the Lightning, an acclaimed collection of prose poems. Study for Obedience, shortlisted for the Booker Prize 2023, is Bernstein’s second novel. Her debut, The Coming Bad Days, was published in 2021. Her fiction, poetry and essays have appeared in publications such as Contemporary Women’s Writing, MAP magazine, Granta and ROOM Magazine. In 2023, she was named by Granta as one of the best young writers in Britain.

Sarah Bernstein

© Alice Meikle‘An absurdist, darkly funny novel about the rise of xenophobia, as seen through the eyes of a stranger in an unnamed town – or is it? Bernstein’s urgent, crystalline prose upsets all our expectations, and what transpires is a meditation on survival itself. It has the uncanny charm of feeling like both a historical work – with its pastoral settings, petty superstitions, and suspicious villagers – and something bracingly modern. In this way it very cleverly, and with great irony, draws a link between a past we’d like to believe is behind us and our very charged present.’

Booker Prize judges 2023: (clockwise from top right) Mary Jean Chan, James Shapiro, Esi Edugyan, Robert Webb and Adjoa Andoh

© David Parry/Booker Prize FoundationSarah Crown, The TLS

‘On the surface, it is a simple story – so simple, in fact, that it borders on plotless: the narrator fills her days with domestic tasks, and fills the pages of her account with pleasing descriptions of the “picturesque” countryside. But if the narrative is loose-knit, the atmosphere clots and complicates with every passing sentence; the quotidian tasks and pleasures are cast into relief by a mounting sense of menace. Everything here feels subtly off-key, oddly angled, tilted towards darkness.’

Cal Revely-Calder, The Telegraph

‘Study for Obedience has a parable’s radiance: the air of the consequential, of a cast who represent us all. Yet it’s too alive a story to rest on obvious messages. Our sympathy for this outsider is muddled by her love of subservience – her peculiar desire to melt her identity into air. Bernstein’s writing is philosophically opaque, as well as electric and elegant. It’s unfortunately fashionable to speak of what novels “say”, to posit that they, and everything else, should convey a single-minded stance. Such childishness melts away before a novel such as this: one that reminds you, beautifully, that fiction is a moral art.’

Miriam Balanescu, The Guardian

‘Bernstein paints from a palette of dread, her fickle narrator imagining that the land itself is trying to “expel” her. Little actually happens, but, mirroring the protagonist’s daily ramblings through the woods, the novel is made up of philosophical, sometimes rhapsodic meanderings logged in meticulous, measured prose.’

Emily Rhodes, The Financial Times

‘An atmosphere of dread, surfacing violence and the uncanny permeates this remarkable novel, palpable even in its opening sentences: “It was the year the sow eradicated her piglets. It was a swift and menacing time.” Study for Obedience interrogates society’s hostility towards outsiders, but the true difficulty of this compelling book lies in its uncomfortable suggestion that when an outcast gains agency, this agency may not be used for society’s good.’

Allan Massie, The Scotsman

‘While enjoying and admiring many passages, I find myself repeatedly asking “what is it all about?” and finding no satisfying answer. This may well be due to my own inadequacy. Likewise, the narrative seems weak to me. “What,” Scott once remarked, “is the plot for but to bring in fine things?” – a good question of course. Well, there are fine things in abundance here, for Bernstein is a very gifted and intelligent writer. There are pages anyone might have been proud of writing. Yet I find myself sighing, “where’s the bloody plot?” Where indeed is the story, for a novel can do without a plot, at least without much of one, but it can’t really do without a story – and I never found myself asking “what happens next?”’

Frank Lawton, The Times

‘It’s all there: the DeLillo-like pulse of anxiety about undefined events; the whiplash sentence shifts; the grand claims made unequivocally; the piling up of clauses and the sudden clarity, followed by a retreat into poetic vagary. It can be exhilarating and confusing. Bernstein has created a mazy style in aid of narrators that get lost in themselves, And as in a maze, you may get lost too.’

Neil Hegarty, The Irish Times

‘The nature of care and the assumptions which underlie the notion of duty are examined, and their various corollaries exposed: carers can all too frequently be subject to degradation, abuse and humiliation; duty can mean relinquishing one’s own dreams and aspirations in the service of others. The protagonist has never experienced belonging, or life within a social order, and as a result has interiorised a sense of nothingness. This, then, is a story of abjection: its engendering and its consequences.’

Study for Obedience interrogates society’s hostility towards outsiders, but the true difficulty of this compelling book lies in its uncomfortable suggestion that when an outcast gains agency, this agency may not be used for society’s good

‘I was trying to think through what it might look like if certain (usually feminised) characteristics associated with passivity could take on a kind of power, especially over the people reinforcing those sorts of gendered norms. That idea comes from the painter Paula Rego – that obedience can, in a sense, also be murderous – it can be harmful to the person demanding obedience. I was also interested in the question of innocence and the really bizarre expectation that, in order for someone’s suffering to be recognised as legitimate, that person needs also to be innocent – whatever that means. The novel’s narrator is a character who has been disempowered and badly treated in a variety of ways and who has also abdicated moral responsibility in other areas of her life, so the question of innocence is a complicated one, for her as well as for us. The question of agency is, I think, also complicated by the narrator’s sense of her own fatedness – her sense of living in a cycle of history she can’t work her way out of.’

Read Sarah Bernstein’s full interview here.

Sarah Bernstein

© Alice MeiklesThe novel’s location is never revealed, other than being described by the narrator as a ‘remote northern country’. In your reading of the book, did you have a real country in mind, and if so which one? Why do you think the author chose to leave the setting nameless and open to interpretation?

The book contains several 21st-century references, such as social media and Microsoft Teams, yet the setting and mood feel almost 19th century. Did you feel that you were reading a modern novel, a historical work, or a book with a time and space all of its own?

One of the book’s epigraphs is a quote from the artist Paula Rego: ‘I can turn the tables and do as I want. I can make women stronger. I can make them obedient and murderous at the same time.’ How do you think this quote relates to the narrator? Clearly, she is obedient, but is she also capable of powerful and deadly acts?

On the one hand, the narrator is the book’s victim; persecuted on an individual level by her own family, and (although not made explicitly clear) as a Jewish woman by society at large and carrying the burden of the past. But to what extent is she also the book’s villain? Is there an interpretation of the book in which she is almost a witch or demon, cursing the villagers and slowly killing her brother, without being fully aware of her own destructive power?

At one point, the narrator discovers a strange mark carved into a wooden post outside her brother’s home. ‘It was not from an alphabet familiar to me, certainly not Latin or Greek; not Cyrillic, Hebrew or Arabic, none of these, no.’ Yet because of the other clues in the book, we might interpret the mark as something anti-semitic. The Booker judges said: ‘The author never uses the words “swastika”, but the reader understands this implicitly, and it’s chilling.’ Did you imagine the mark to be a swastika? What else might it be?

While both the narrator and her brother are Jewish, only she faces hostility from the local community, while he is embraced warmly and integrated into village life, suggesting there is something about her as an individual that repulses them, rather than her Jewishness alone. What do you think it is?

In the Guardian, Chris Power writes: ‘Reading a book in which details are so vaporous seeds interpretative doubt: might the fact the story’s setting doesn’t match any real-world country, and that the locals the narrator interacts so uneasily with remain ciphers, mean it should be read as a fable?’ Would you agree that the book has, in Power’s words, ‘a fable-like energy’ and if so how does that affect your interpretation of the events in the book?

Natural events - a dog with a phantom pregnancy, cows gone mad, piglets killed by their own mother - take on a deeper, darker significance in the book and lend it an air of folk horror. To what extent did you read the book as a horror story?

The book contains over a dozen references to other works of literature; passages which allude to writing by, among others, Virginia Woolf, Walt Whitman, Susan Sontag and Penelope Fitzgerald. Were you aware of any of these references while reading the novel, and why do you think the author decided to list them at the end of the novel?

Some critics have taken issue with the book’s lack of plot or story. Few things of significance happen, and those that do are open to interpretation because the narrator’s account is either unreliable or lacking essential detail. Did you feel this was a book with little or no plot, and can a book with almost no plot still be great?

The Jewish Chronicle: Sarah Bernstein: The Jewish author on the road to greatness

Public Books: ‘Gestures of refusal’: A conversation with Sarah Bernsteine

The Lottery and Other Stories by Shirley Jackson

Pew by Catherine Lacey

Cursed Bread by Sophie Mackintosh

The Enigma of Arrival by V. S. Naipaul

The Coming Bad Days by Sarah Bernstein

You Let Me In by Camilla Bruce