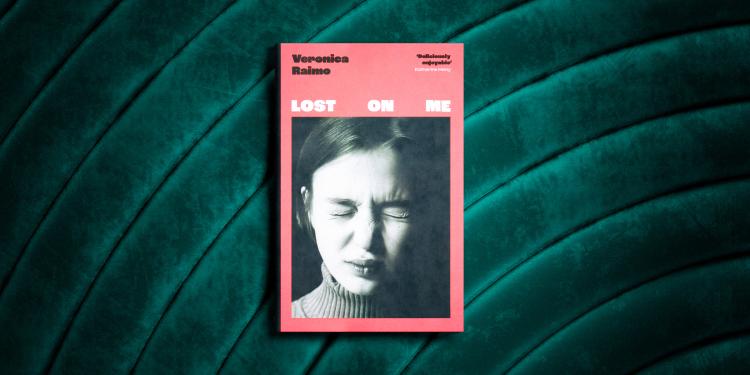

Reading guide: Lost on Me by Veronica Raimo, translated by Leah Janeczko

A funny, sharp, wonderfully readable novel that takes us to the heart of an obsessive, unpredictable Italian family

Lost on Me, originally written in Italian, is longlisted for the International Booker Prize 2024. Read an extract from the opening chapter here

Vero has grown up in Rome with her eccentric family: an omnipresent mother who is devoted to her own anxiety, a father ruled by hygienic and architectural obsessions, and a precocious genius brother at the centre of their attention. As she becomes an adult, Vero’s need to strike out on her own leads her into bizarre and comical situations. As she continues to plot escapades and her mother’s relentless tracking methods and guilt-tripping mastery thwart her at every turn, it is no wonder that Vero becomes a writer - and a liar - inventing stories in a bid for her own sanity.

My brother dies several times a month.

It’s always my mother who phones to inform me of his passing.

“Your brother’s not answering my calls,” she says in a Whisper.

To her, the telephone bears witness to our permanence on Earth, so if there’s no answer, the only possible explanation is the cessation of all vital functions.

When she calls to tell me my brother is gone, she’s not looking for reassurance. Instead she wants me to share in her grief. Suffering together is her form of happiness; misery shared is misery relished.

Sometimes the cause of death is banal: a gas leak, a head-on collision, a broken neck from a bad fall.

Other times the scenario is more complex.

My mother’s call last Easter Monday was followed by another one from a young Carabiniere officer.

“Your mother has reported your brother’s disappearance.

Can you confirm this?”

They hadn’t heard from each other for maybe a couple hours. He was out to lunch with his girlfriend, and she was agonizing over why he wasn’t out to lunch with the person who’d brought him into this world.

I tried to reassure the young carabiniere. Everything was under control.

“No,” he burst out, “everything is not under control. All hell has broken loose on our switchboard.”

Veronica Raimo

On that particular occasion my brother wasn’t yet dead, but was at death’s door. He was being held captive in a parking garage, having been kidnapped and tortured by henchmen sent out by the Italian Democratic Party. He’d recently become culture councillor of Rome’s third municipal district, and at times there were disagreements with fellow party members.

“Don’t bicker with anyone,” my mother had warned him.“

Mamma, I don’t bicker, I do politics.”

“All right, just make up afterwards.”

After ascertaining that her son is still alive, my mother always feels mortified. She pouts like a twelve-year-old girl. Her voice even turns into a twelve-year-old girl’s. How can you get angry at a little girl?

“You think I should bring the carabinieri some pastries?” she asks in that little voice.

Come to think of it, who knows why she called the carabinieri and not the regular police? I don’t dare pose the question, since it risks doubling the number of calls she’ll make next time. The fire department, for example, or civil protection. She’s never thought of them before.

When she’s in a state of panic, my mother bargains with the Lord and imposes fioretti on herself: no eating sweets, no going to the movies, no reading magazines, no listening to Rai Radio 3, for weeks, months, years. These days she can’t go to the hairdresser’s or watch TV. Sometimes the combination is no Radio 3 and no sweets. Or no coffee and no new shoes.

She mixes them, matches them—it depends.

I go over to see her because I’m worried.

“Ah, Verika, it’s you.” My mother calls me Verika. “I was hoping it was your brother.”

She still lives in the apartment where I grew up, in a residential district in the northeast outskirts of Rome. The same district where her son has been made culture councillor. I wish I could convince her to convert at least one of her fioretti into a good deed. “Do a little volunteer work,” I tell her. “I’m sure the Lord will approve.”

She shakes her head, and as she does she asks me to turn on the TV and tell her what’s going on in the world. Though she covers her eyes with her hands, I can see her peeking between her index and middle fingers. She gropes for the remote and turns up the volume. “Humph. You couldn’t hear a thing.”

While my brother was still being held hostage by the Democratic Party’s thugs, my mother awaited the fatal phone call, trembling. “I vowed I would throw myself out the window.”

“What a pleasant thought, Mamma. That way I’d have spent Easter Monday with my brother butchered and my mother splattered on the sidewalk.”

Then a thought strikes me. “So, if they’d killed me instead, would you still have jumped?”

Silence.

She doesn’t look at me because she still has one hand covering her eyes.

“Well? Would you have jumped?”

“Oh, don’t ask silly questions.”

On that particular occasion my brother wasn’t yet dead, but was at death’s door. He was being held captive in a parking garage, having been kidnapped and tortured by henchmen sent out by the Italian Democratic Party.

When I get back home and think about it, there’s something that doesn’t add up in her near-suicide scenario: there isn’t a single window in my parents’ apartment that anyone could possibly jump out of. They’re all too narrow, because they’ve been split in two.

My father had a fixation with dividing up rooms, for no reason at all. He would simply build a wall through them. He built walls in rooms—there’s no other way to put it.

There were four of us living together in a sixty-square-meter apartment, which he’d managed to split up into three bedrooms, a living room, a kitchen, a dinette, a veranda, and two bathrooms, plus a long tunnel of overhead storage space that ran the full length of the apartment and lowered the ceiling. A particularly tall person would’ve banged their head against it, but no one in our family had that problem.

There were no real doors to speak of—just sliding panels without locks. It was like living on a theater set: the rooms were purely symbolic, simulations for the benefit of spectators.

For part of my childhood, my bedroom existed only at night. During the day it became a hallway again. When it was time to go to sleep, I would close two folding doors and pull down a section of the wall that was actually a Murphy bed. In the morning it all disappeared; the set was changed.

Panels were slid back, curtains raised. Later, my bedroom was moved into my brother’s, a tiny rectangle squeezed into one corner of the room like a horizontally positioned broom closet. The window—like all the others—was bisected by the wall. If I wanted to look out at the world, I had to make do with an opening as wide as a minibar door.

“Just so you know, you wouldn’t have fit through the window,” I write to my mother.

“Thank you, dear,” she replies. “I’ll keep that in mind.”

Leah Janeczko