Read an extract from The Line of Beauty by Alan Hollinghurst

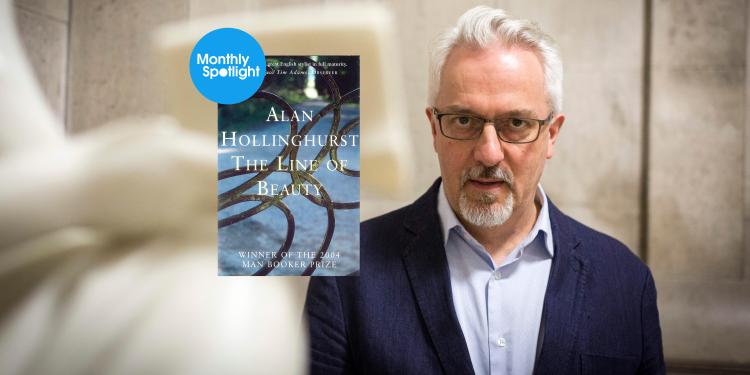

Alan Hollinghurst’s 2004 Booker Prize-winning novel defines a decade, as a young man navigates a world of privilege to which he can never truly belong

To mark the 20th anniversary, the author reflects on the transformative impact of his Booker triumph with The Line of Beauty – a novel that propelled LGBTQIA+ narratives into the literary mainstream

Your novel The Line of Beauty won the Booker Prize in 2004. How did it feel to win, and what impact did the win have on your career, both immediately and over the years that followed? How do you look back on the experience of winning 20 years later?

I’m not an especially competitive person, and having been shortlisted for the Prize ten years earlier I felt I had the advantage of a certain detachment from the whole thing: wonderful to be shortlisted, fabulous to win, but absolutely fine not to win. The Line of Beauty had come out five months earlier, and had generally been well received, and I was happy to have got that far. Winning, of course, changed my life and my prospects at once: a huge increase in income, foreign rights sold in many new territories, and the start of nearly two years of whizzing round the world talking about the book. I decided to ride the wave and get the most out of it, and it was a very happy experience – only slowly undermined, towards the end, by a feeling that I couldn’t keep answering the same ten questions for much longer. I was pining to be alone at my desk and writing something new.

Were there any memorable moments during the Booker Prize ceremony or in the run-up to it? How did you celebrate your win?

I was teaching at Princeton at the time, so I missed all the nerve-racking build-up back home in the UK. Picador, my publishers, flew me back the day before the ceremony, and I went through the whole evening of the prize-giving in a state of dreamlike passivity and calm, which I can’t really explain, but was very grateful for. There was a quite strong expectation that David Mitchell would win, and the TV cameramen (who of course know the outcome in advance) appeared to be gathered round his table; but then my name was read out, and they swivelled as one towards me. I’ve never liked being the centre of attention, but fortunately I’d scribbled down a few words before leaving for the dinner, and was able to say something vaguely coherent. Then suddenly I was talking to Kirsty Wark on Newsnight, then at an international press conference, then at a marvellous party at Soho House into the small hours. Then a 5am start for a 48-hour blur of interviews.

2004 Man Booker Prize winer, Alan Hollinghurst

Immediately after the prize announcement, several publications noted that The Line of Beauty was ‘the first gay novel’ to win the prize. What did you make of comments like that? Did they seem overly simplistic, or did you feel that the book – and its Booker success – was opening doors for other writers? How do you think the book would be perceived had it been published now, two decades later?

It was the fourth novel I’d published, all of them written from a gay perspective, so to me it just seemed how things were. I had two main feelings about that kind of press attention – that it was predictable and trivial and occasionally funny (‘Gay Sex Wins Booker’ I remember was one headline), and that it was a cheering sign that gay content and point-of-view, and gay sex, indeed, hadn’t been reasons to disqualify the book from attention but were celebrated as part of its interest. If a fuss was made about the novel’s gayness, it seemed also to suggest that the time was at hand when it might no longer cause a fuss.

The novel celebrates its 20th anniversary this year, and is set around 40 years ago, yet it continues to find new audiences. What is it about the book that you think speaks to modern readers and are you surprised how much it has endured?

It’s really not something I can explain – though I’m very glad it still sells and happy when people tell me they’ve enjoyed it. Perhaps to those who lived through the 1980s it has deeper resonances. And to younger readers it is informative about a period they didn’t experience. I remember realising when it was filmed in 2006 that it had become historic in a new way – Dan Stevens, who played Nick, was born in 1982 and barely remembered Thatcher in power, and here he was dancing with her at a party.

There was a quite strong expectation that David Mitchell would win, and the TV cameramen appeared to be gathered round his table

The book paints a vivid picture of the 1980s, from the AIDS crisis to the dramatic socio-economic changes of the time. Where did you draw your inspiration and references from? Were there any particular accounts from the time – or other works of fiction – you used for research?

Well, I had lived through that period and had pretty vivid memories of its political and social convulsions, and of the devastations of AIDS. I moved to London in 1981 and lived for the first two years in Notting Hill, so I had a clear sense of the geographical terrain of the novel. I’ve always been wary of research – beyond the basic need to get things right – and I treasure small details that trigger the imagination, which is really what counts when writing any kind of novel. I read Alan Clark’s Diaries, which revealed to me the surprisingly sexual dimension of Thatcher’s hold over her almost entirely male cabinets. And I read Ian Gilmour’s Dancing with Dogma, whose cover photo of Gilmour and Thatcher on the dancefloor gave me the idea for a key scene in my book. Beyond that I just made it all up.

Tell us about a book that made you want to become a writer. How did it inspire you to embark on your own creative journey, and how did it influence your writing style or aspirations as an author?

All through my teenage and student years I wrote poems, and my models were drawn from wonderful anthologies we had at school: Fifteen Poets: From Chaucer to Arnold, which was the book that really inculcated the language, syntax and expressive possibilities of poetry into my system, and large chunks of which – Keats, Tennyson, Wordsworth – I learned by heart and remember still; and Poets of Our Time (1965),which got me reading, and imitating, Laurie Lee, Ted Hughes and R. S. Thomas. These books set me going on a lifetime of reading poetry, which I stopped producing myself as soon as I got drawn into writing novels. But I think I took from this early immersion in poets of all kinds an interest in sound and rhythm and structure that has stood me in good stead.

From Tolkien I took an enduring, nearly mystical sense of landscape, and from Wodehouse a model of social comedy which would be deepened later on by reading Austen and Henry James and Waugh

Was there a book that defined your early or teenage years, or that made you fall in love with reading? In what ways did it shape you, or your worldview?

My twin fictional obsessions in the period from childhood into adolescence were Tolkien (I read The Lord of the Rings six times in succession) and P. G. Wodehouse, whom I still read with joy, and who in his way made just as deep an impression on me as Tolkien, whom I now find very hard to get through. They were both fantasists, one solemn, one extremely funny, but from Tolkien I took an enduring, nearly mystical sense of landscape, and from Wodehouse a model of social comedy which would be deepened later on by reading Austen and Henry James and Waugh. I’m always very grateful to, and remember, books that make me laugh, and also those which create a strong and particular sense of place.

Which book you are currently reading, and what made you pick it up?

I’m reading Peter Parker’s huge new anthology, Some Men in London – an astonishing collage of diaries, letters, newspaper reports depicting the day-to-day existence of gay men in London between the end of the War and the Sexual Offences Act of 1967. Peter and I were born a mere seven days apart, and went to the same school, and though we rarely see each other now I have a nice sense of our pursuing parallel careers in exploring the gay past — one of us as a novelist, the other as a nearly omniscient biographer and critic: I never stop learning things from him.

What would you consider your all-time favourite book? How has it left a lasting impression on you?

The Portrait of a Lady – the book in which Henry James spreads his wings, and shows, almost to his own astonishment, what he, and the English novel, are now capable of.

Lastly, is there a hidden gem from the Booker Library – an underappreciated title from among the 600+ books that have been nominated for the Booker and International Booker Prizes over the past half-century – that you would recommend to others, and if so why?

Penelope Fitzgerald’s Offshore, which won in 1979, and was scorned at the time by male pundits for being short and by an old woman: two of the things that are its particular strengths. It’s still less celebrated than other books from her marvellous late-flowering career, but seems to me the most magical of all of them. I’ve read it many times, never able to understand how she does it, how a book of a mere 130 pages can contain so much of life and history and comedy and despair.

Offshore by Penelope Fitzgerald

Winner The Booker Prize 2004