Q&As with the 2021 nominated authors

Read our interviews with the nominated authors for this year’s Booker Prize

Q&A

'Psychological trauma, when not attended to, is passed down like a baton'

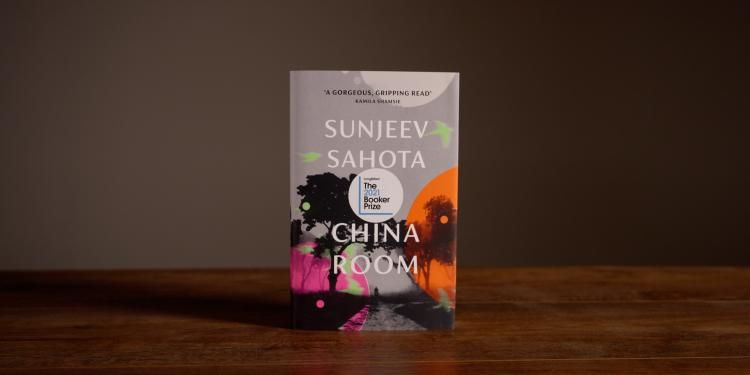

Sunjeev Sahota speaks to us about avoiding sentimentality and writing his Booker Prize-longlisted China Room.

How does it feel to have China Room longlisted for the Booker?

I was very moved when I found out. It’s such a personal book and so this longlisting feels quite personal, too.

Which authors have influenced or inspired your own writing?

Joan Didion’s terse lyricism inspires me, and I hope I’ve learned something about drama and humour from reading Beckett.

What is your favourite Booker-winning or Booker-shortlisted novel?

Disgrace. The Conservationist. Amongst Women.

What are you working on next?

Another novel.

China Room opens with a fable-like setup: three women married to three brothers; none of the women knows which brother she is married to. There are many possible plots that could grow from there – did you know for a while which one you wanted to write?

I knew that there would be a misidentification, but the full consequences of it were bleary to me until I alighted on the narrative of the great-grandson. Somehow, and perhaps this is apt, given that the book is interested in occlusion and ideas of inheritance, I needed the lens of a more personal narrator to bring into proper focus the 1929 narrative.

A portion of your book is full-blown romance. The thrill of that is both conveyed and offset by extremely precise prose. Can you tell us a bit about your writing process in that part of the story?

Precision debars sentimentality, which is important for me to avoid. More generally, I do try to withhold as much as possible, to both clear a space in which ideas and feelings can be perceived and not asserted, and to also reflect the fact that in life everyone, even those closest to you, is in the deepest sense a stranger. I like it when fiction respects the reality that no one truly knows anyone else, when characters aren’t fully knowable. For the lovers in the novel, this withholding in the prose creates a gap which it is hoped the reader rushes to fill with their own hopes – I think this tension between knowing and longing is necessary to how the novel works. In the contemporary romance, however, the withholding manifests as all silence and noticing, at least on the narrator’s part, which feels right to me because, not only is he wary, he is also spellbound by Radhika. He really does believe that he loves her.

There are two strands to the narrative. On the surface, the modern-day strand is a return to the setting of the historical one. But they are unified by more than that, and in particular by a legacy of disenfranchisement – for women, and for immigrants to the UK. You might even say the traumas of the contemporary narrator are a stacked-up inheritance. To what extent do you think historic forms of prejudice are invisibly borne elsewhere?

We’ve always intuited – from the unexplained sadness of a parent, the freighted attitude in a room – that psychological trauma, when not attended to, is passed down, like a baton, and recent science seems to not only bear this handover out, but explains that this happens via alterations in our genetic markers. What’s fascinating is that studies also (tentatively) suggest that if you can reckon with the trauma, then subsequent generations are spared. This is what the narrator means when he says towards the end of the novel that ‘the underlying hurt does not go away and can only be paid attention to’: we must work out a way to accept our pain, which doesn’t, of course, mean that the pain is acceptable.

Sunjeev Sahota . © GL Portrait / Alamy