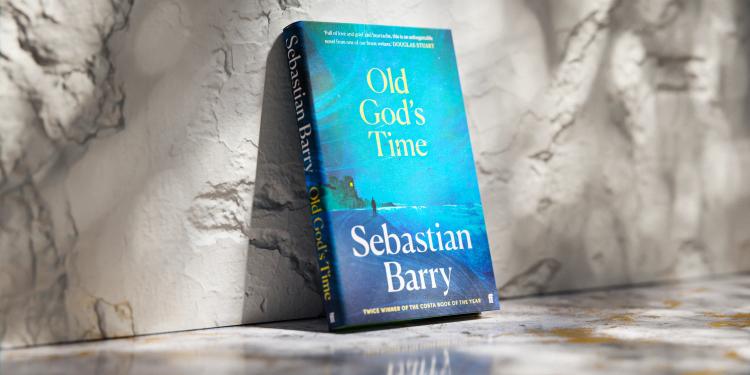

Book recommendations

In his beautiful, haunting novel, in which nothing is quite what it seems, Sebastian Barry explores what we live through, what we live with, and what may survive of us

Recently retired policeman Tom Kettle is settling into the quiet of his new home, a lean-to annexed to a Victorian Castle overlooking the Irish Sea. For months he has barely seen a soul, catching only glimpses of his eccentric landlord and a nervous young mother who has moved in next door.

Occasionally, fond memories of the past return - of his family, his beloved wife June and their two children. But when two former colleagues turn up at his door with questions about a decades-old case, one which Tom never quite came to terms with, he finds himself pulled into the darkest currents of his past.

Sometime in the sixties old Mr Tomelty had put up an incongruous lean-to addition to his Victorian castle. It was a granny flat of modest size but with some nice touches befitting a putative relative. The carpentry at least was excellent and one wall was encased in something called ‘beauty board’, its veneer capturing light and mutating it into soft brown darknesses.

This premises, with its little echoing bedroom, its tiny entrance hall, a few hundred books still in their boxes and his two old gun cases from his army days, was where Tom Kettle had in his own words ‘washed up’. The books remembering, if sometimes these days he did not, his old interests. The history of Palestine, of Malaya, old Irish legends, discarded gods, a dozen random matters that at one time or another he had stuck his inquisitive nose into. The stirring sound of the sea below the picture window had been the initial allure but everything about the place pleased him – the mock-Gothic architecture, including the pointless castellation on the roofline, the square of hedges in the garden that provided a windbreak and a suntrap, the broken granite jetties on the shoreline, the island skulking in the near distance, even the crumbling sewerage pipes sticking out into the water. The placid tidal pools reminded him of the easily fascinated child he once had been, sixty years ago, the distant calling of today’s children playing in their invisible gardens giving a sort of vaguely tormenting counterpoint. Vague torment was his forte, he thought. The sheeting rain, the sheeting sunlight, the poor heroes of fishermen trying to bring their rowing boats back against the ferocious current into the little cut-stone harbour, as neat and nice as anything in New Ross where he had worked as a very young policeman – it all seemed delightful to him. Even now in winter when winter was only interested in its own unfriendly harshness.

He loved to sit in his sun-faded wicker chair in the dead centre of his living room, feet pointed towards the affecting murmurs of the sea, smoking his cigarillos. Watching the cormorants on the flourish of black rocks to the left of the island. His neighbour in the cottage next door had set up a gun-rest on his balcony and sometimes in the evenings would shoot at the cormorants and the seagulls as they stood there on the rocks innocently, thinking themselves far from human concerns. A few falling like fairground ducks. As peaceably, as quietly, as you can do such a thing. He had not been to the island but in the summer he had witnessed the parties of people going out to it in the rowing boats. The boatmen leaning into the oars, the current ravishing the keels. He had not been, he did not wish to go, he was quite content just to gaze out. Just to do that. To him this was the whole point of retirement, of existence – to be stationary, happy and useless.

That untroubled February afternoon a knocking on the door disturbed him in his nest. In all the nine months he had lived there, not a soul had bothered him aside from the postman, and on one peculiar occasion Mr Tomelty himself, in his gardener’s weeds, asking for a cup of sugar, which Tom had not been able to provide. He never took sugar because he had a touch of diabetes. Otherwise, he had had his kingdom and his thoughts to himself. Although why did he say that, when his daughter had been out to see him a dozen times? But Winnie could never be said to disturb him, and anyway it was his duty to entertain her. His son never came, not so far, not because he didn’t wish to, but because he lived and worked in New Mexico, out near the Arizona border. He was a locum on one of the pueblos.

Mr Tomelty had portioned out his property into segments: Tom’s place, and the Drawing Room Flat, and indeed the Turret Flat, currently – suddenly – occupied by a young mother and her child, who had arrived in the dark midwinter before Christmas, in a rare snowfall. No doubt Mr Tomelty was an efficient landlord. He was certainly wealthy, owning this property, Queenstown Castle, and also an imposing hotel on the seafront in Dunleary, called The Tomelty Arms, an aristocratic sort of name. But his usual guise, at least in Tom’s experience, was that of an age-bent gardener, passing along the path under the picture window with a creaking wheelbarrow, like a figure in a fairy tale. All summer and autumn old Mr Tomelty had looked for weeds and found them and ferried them off to his swelling dunghill. Only winter had interrupted his task.

The knocking came mercilessly again. Now, for good measure, the doorbell. Then again. Tom pulled his bulky, solid form up from the chair, promptly enough, as if answering some instinct of duty – or perhaps merely humanity. But it was also an obscure bother to him. Yes, he had grown to love this interesting inactivity and privacy – perhaps too much, he thought, and duty still lurked in him. The shaky imperative of forty years in the police, despite everything.

Sebastian Barry

© Hannah CunninghamHe felt a little lock in his smile before it reached the full width of older days. Full welcome, full enthusiasm, full energy, seemed risky to him somehow

Through the glass door he could see the outlines of two men, possibly in dark suits – but it was hard to tell as the big rhododendron behind them lent them an inky halo, and the daylight was losing its grip on things anyway. These were the few weeks of the rhododendron’s heartfelt blooming, despite the wind and the cold and the rain. Tom recognised the shifting-about that the figures were engaged in, even through the frosted glass. People not sure of their welcome. Mormons maybe.

His front door didn’t sit well on its hinges and the lower edge scraped dramatically. There was a regrettable fan-shaped mark on the tiles. He opened it, it released its tiny screech, and to his surprise two young detectives from his old division stood there. He was puzzled, and a little alarmed, but he knew them immediately. Not quite by name, but nearly. How could he not? They were kitted out in that unmistakable civilian mufti that clearly announced they were not civilians. They had the poorly shaven faces of men who rose early and there was an air about them that whether he liked it or not drew him right back to his own early days policing, the unlikely innocence of it.

‘How are you doing, Mr Kettle?’ said the one on the right, a nice big lump of a young man with a brushstroke for a moustache, a touch Hitlerian if the truth were known. ‘I hope you won’t mind us coming out – disturbing you?’

‘I don’t mind, I don’t mind, you’re not, you’re not,’ said Tom, doing his best to conceal the lie. ‘You’re welcome. Is everything alright?’ Many times he had brought unwelcome news himself to people in their houses – to people in their private minds, in their dreamlike privacy, to which he had added only troubles, inevitably. The hopeful, worried faces, the gobsmacked listening, sometimes the terrible crying. ‘Are you coming in?’

They were. Inside the door they said their names – the wide man was Wilson and the other was O’Casey – which right enough he seemed to half-remember, and they exchanged pleasantries about the awful weather and how snug his quarters were – ‘very cosy,’ Wilson said – and then he set about making them tea in his galley kitchen. Indeed it might as well have been on a boat. He asked Wilson to turn on the overhead light and after gazing about a few moments Wilson located the switch and obeyed. The meagre bulb was only forty watts, he must do something about that. He was going to apologise for the books still being in boxes but he said nothing. Then the two young fellas sat themselves down on invitation and they fired the professional bonhomies back and forth through the bead curtains with the happy ease of men in a dangerous profession. Policing always had its salt of danger, like the sea itself. They were fairly at ease with him, but also respectful, as befitted his former rank, and maybe also the loss of it.

Even as they talked Tom felt obliged to whatever gods ruled that fake castle to gaze out occasionally on the copper-dark sea just now getting scrubbed over bit by bit by worse darkness. It was four in the afternoon and night was creeping in to take everything away till only the weak lights of the lamps on Coliemore Harbour would bounce themselves a few yards out onto the water, speckling the darkling waves. The Muglins beacon beyond the island would soon spark to life and even further out, deeper than he knew, away off on the horizon, the Kish Lighthouse herself would begin to show her heavy light, laboriously sweeping the heaving deeps. He thought of the fish in there, lurking about like corner boys. Were there porpoises this time of year? Conger eels coiling in the darkness. Pollock with their leaden bodies and indifference to being caught, like failed criminals.

Soon the pot and the three cups were set on an old Indian side table that Tom had won in a long-ago golf tournament. The really good players, Jimmy Benson and what was that fella’s name, McCutcheon, had been off sick from the flu that was going around at that time, so his meagre talents had carried the day. He always smiled when he thought of that but he didn’t smile just now. The nickel tray improved to silver in the light.

He was mildly troubled that he had no sugar to offer them.

He turned the wicker chair about so he could face them and, summoning again his old friendly self which he wasn’t sure he still possessed, he lowered himself onto the creaking reeds and smiled broadly. He felt a little lock in his smile before it reached the full width of older days. Full welcome, full enthusiasm, full energy, seemed risky to him somehow.

‘We got the heads-up from the chief that you might be able to help us with something,’ said the second man, O’Casey, as if just for contrast a long thin person, with that severe leanness that probably made all his clothes look too big on him, to the despair of his wife, if he had one. Tom at this point was just letting the tea steep in the pot a few moments and his head was moving from side to side. When his friend Inspector Butt had come from Bombay in the seventies to try to probe the strangenesses of Irish policing – no guns, Ramesh could not get over that – he had witnessed that enchanting head movement, and mysteriously adopted it. It went with the table.

‘Well, sure,’ he said, ‘I’m always here to help, I told Fleming that.’ Indeed he had, regrettably, told Detective Superintendent Fleming that, as he went out the door on the last day in Harcourt Street, with a burning headache after the send-off the night before – not from drinking, because he was a teetotaller, but from only reaching his bed in the small hours. Tom’s wife June’s ‘mother’, the dreadful Mrs Carr, had scandalised them both when they were a young couple with kids by insisting those selfsame kids, Joe and Winnie, were in bed by six, until they were all of ten years old. Mrs Carr was a termagant but she had been right about that. Sleep was the mother of health.

‘It’s something that’s come up and he thought, the chief thought, it might be useful to hear your thoughts on it,’ said the detective, ‘and, you know.’

‘Oh yes?’ said Tom, not uninterested, but all the same with a strange surge of reluctance and even dread – deep, deep down. ‘Do you know, lads, the truth is I have no thoughts – I’m trying to have none, anyhow.’

They both laughed.

Old God’s Time by Sebastian Barry