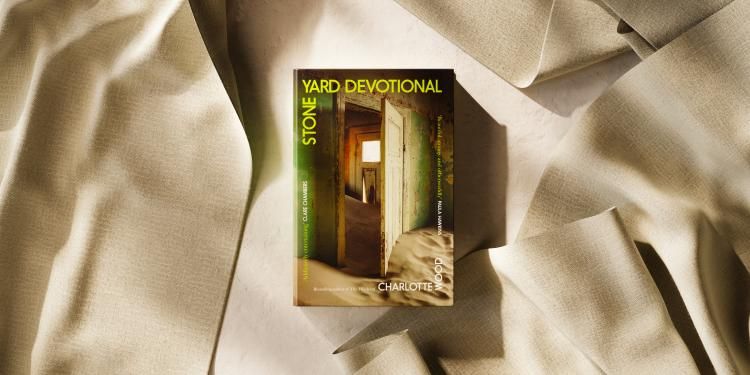

An extract from Stone Yard Devotional by Charlotte Wood

Stone Yard Devotional is longlisted for the Booker Prize 2024. Read an extract from the opening chapter here

Burnt out and in need of retreat, a middle-aged woman leaves Sydney to return to the place she grew up, taking refuge in a small religious community hidden away on the stark plains of the Australian outback. She doesn’t believe in God, or know what prayer is, and finds herself living a strange, reclusive existence almost by accident.

But disquiet interrupts this secluded life with three visitations. First comes a terrible mouse plague, each day signalling a new battle against the rising infestation. Second is the return of the skeletal remains of a sister who disappeared decades before, presumed murdered. And finally, a troubling visitor plunges the narrator further back into her past…

Published in the UK by Sceptre.

DAY ONE

Arrive finally at about three. The place has the feel of a 1970s health resort or eco-commune, but is not welcoming. Signs on fences, or stuck on little posts by driveways: no entry. no parking. A place of industry, not recreation.

I park in a nondescript spot near a fence, and sit in the quiet car.

~

On the way here I stopped in the town and visited my parents’ graves for the first time in thirty-five years. It took some time for me to find them in what is called the ‘lawn cemetery’, the newer part fenced off – why? – from the original town grave- yard with its crooked rows of tilting white headstones and crosses. That old part is overlooked by enormous black pine trees; ravens and cockatoos scream from their high branches. The lawn cemetery, by contrast, is a dull, flat expanse filled with gently curved rows of low, ugly headstones of identical dimensions. Neater, I suppose (but why should a cemetery be neat?).

There is no lawn, just dusty dead grass.

To find my parents I had to recall the cold, unsheltered feeling I had – physically, I mean – at each of their funerals. There had been the sensation of too much space around me there, at the place where my father, then later my mother, were sent into their adjacent shafts of opened earth. (It seemed callous to me back then, to lower a person into a hole in the ground using ropes and cords instead of arms.) But walking around the cemetery now, remembering that sensation helped me find the spot again. I stood before my mother’s and father’s gravestones, two machine-cut and polished pieces of stone. The colour and design of the stones and the words on them seemed to bear no trace of either of my parents, though I must have decided on, approved of, them.

Someone had pushed some ugly plastic flowers into the small metal grate beside the headstones. Perhaps there are volunteers who go around leaving fake flowers at unvisited graves. Who else would want to mark my parents’ burial place after all this time? The plastic of the flowers had turned grey, every part of them, though they must have once been luridly coloured like those I could see sticking up from the little metal vases at other headstones: ragged synthetic petals in puce and maroon and white with dark green stems, angled here and there with artificial nodules and leaves. I stood on the grass and looked at the ugly flowers, then at my parents’ names carved into each slab in front of me. And I realised: Your bones are here, beneath my feet. I squatted then, those few feet of earth between their bodies and mine, and I kissed my fingers and pressed them to the crackly grass.

Charlotte Wood

© Carly EarlI squatted then, those few feet of earth between their bodies and mine, and I kissed my fingers and pressed them to the crackly grass

~

Walking back to the car I remembered something else: a phone call, many months after my mother’s death. A man’s voice quietly telling me her headstone was ready. I recall standing by the laundry door with the phone in my hand, my outsides unaltered but everything within me plummeting. Like a sand- bank collapsing inside me.

~

Near the end of the drive the sky darkened, turned drizzly. The road coiled up a steep hill, entering a tunnel of thick bush – my car struggled on the wet bitumen – and then on the other side it opened out into these endless, shallow, angular plains, bare as rubbed suede.

Place names I thought I’d forgotten returned to me one by one: Chakola, Royalla, Bredbo, Bunyan. Jerangle, Bobundara, Kelton Plain, Rocky Plain, Dry Plain, like beads on a rosary. Like naming the bones of my own body.

~

A little after I arrive, the sun comes out. I get out and look around me, trying to work out where I should go. There are some skinny pencil pines, a few dripping eucalypts, a lot of silence. Three or four small wooden cabins painted a drab olive; green peaked tin roofs.

I wander the grounds for a time, eventually finding a shed marked office, and knock on the door. A woman appears, introduces herself as Sister Simone. She pronounces it Simone, traces of an accent (French?). Indeterminate age, business-like but soft-looking at the same time. Scrawnyish. Quite yellow teeth. She apologises for not having come out to greet me; she is busy, but a housekeeper will show me around if I wait for a bit. She tells me with a teeth-showing smile – more a grimace – that she’s looked me up on the internet and that my work sounds ‘very impressive’. Her tone seems lightly insulting. I smile and tell her the internet is very misleading. She pauses, then says coolly that saving God’s creatures most certainly is important work. She’s slightly cross, I think. Not accustomed to disagreement. We bare our teeth at each other again and she closes the office door.

~

Anita, the housekeeper. Chatty and broad-bummed. Shivering a little in her maroon fleece vest over a turquoise shirt, navy pants. She leads me around the buildings and grounds, and I trot behind her as she rattles on. She could never be a nun – imagine getting up for Vigils at five a.m. In winter! Plus, they can’t watch Netflix: ‘That’s never going to work for me.’

She unfolds her arms now and then to point at something – shop, old orchard, guest cabins; gestures further off to indicate the paddocks, a small dam – then refolds them against the cold and we take off towards a little stone chapel. I open my mouth to say, It’s okay, I don’t need to see inside, but don’t want to be rude. We push through a big wooden door. Anita’s chatter doesn’t stop but turns to a whisper, though there is nobody in the church. She has just learned, she says, that this is not called a chapel – chapels are privately owned. This is a Consecrated Church. When they come in here it’s called the Liturgy of the Hours, she whispers, enunciating these words as if from a foreign language. Which I suppose they are.

- By

- Charlotte Wood

- Published by

- Sceptre