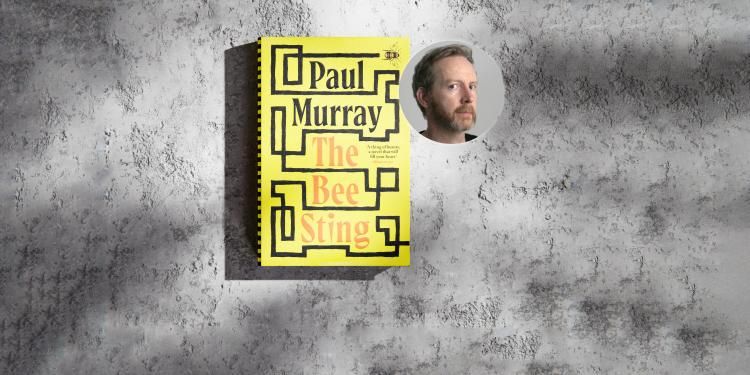

An extract from The Bee Sting by Paul Murray

A patch of ice on the road, a casual favour to a charming stranger, a bee caught beneath a bridal veil – can a single moment of bad luck change the direction of a life?

With The Bee Sting shortlisted for the Booker Prize 2023, we spoke to Paul Murray about getting the details of Ireland’s Midlands right, and why he wanted to write about climate change

Read interviews with all of the shortlisted and longlisted authors here.

How does it feel to be nominated for the Booker Prize for the second time, and what would winning the prize mean to you? Does it feel different this time around, 13 years later?

It’s great to be nominated, and to share the longlist with such amazing authors. I was last nominated in 2010 with Skippy Dies. Obviously the world has changed a lot since then, so it makes me very happy that this book has connected with people. The first time out I found the experience somewhat overwhelming. My friends keep telling me to enjoy it this time, and that’s what I’m trying to do.

There are four Irish authors on this year’s Booker longlist - more than any previous year - and some commentators have argued that there could have been even more. Ireland obviously has a rich literary tradition, but there seems to be a lot of exciting fiction coming out of the country just now - why do you think that might be?

I think it’s a combination of things. We have a very active Arts Council that grants funding to writers – established and emerging – with the explicit goal of buying them time to write their books. Writing is not a particularly remunerative profession, so that support can make a big difference. Also, and maybe even more important, when you’re starting out on the marathon of writing a novel, it’s a mark of faith and as such it’s hugely beneficial.

Beyond that – we have a very strong reading culture in Ireland. The libraries here are great, we have excellent, well-curated bookshops. So books are a part of the national conversation in a way they might not be elsewhere. The successes of the past meant that growing up I felt like writing was something that was available to me as a possible future, in a way that other art forms did not. Is this a particularly fertile period? I feel like there’s always been exciting fiction coming out of the country – the only time it seemed to lag was during the Celtic Tiger, when rents skyrocketed, and simultaneously all these highly-paid jobs materialized to tempt younger writers away from their novels.

How long did it take to write The Bee Sting, and what does your writing process look like? Do you type or write in longhand? Are there multiple drafts, long pauses, or sudden bursts of activity? Is there a significant amount of research and plotting before you begin writing?

It took about five years, give or take. I spent some time going down rabbit holes of one kind and another before I finally started in earnest. I always write the first draft in longhand, then I type it up, then there are two or three major revisions before I’ll send it to the editor. Once it’s rolling the process is pretty steady – I treat it like a regular job, show up at my desk from Monday to Friday week after week till it’s done. I don’t take any serious time off from it – I need to stay in touch with the material, and anyway even when I’m not working on it I’ll be thinking about it. So holidays feel somewhat redundant.

The last book I wrote was set in an investment bank, which entailed a lot of research. For this one I didn’t need to do any deep dives – it was more about getting the Midlands details right, the Millennial details right, the GAA stuff, and that could be researched by talking to people. The plot appears as I write – that is, once I start writing page 1, I’ll begin to get ideas for page 2, page 50, page 400. So there’s usually a fairly elaborate plan at a fairly early stage – though I try not to get too attached to it, because so much changes with the writing itself.

Paul Murray

© Lee PelligriniThe successes of the past meant that growing up I felt like writing was something that was available to me as a possible future, in a way that other art forms did not

Where exactly do you write? What does your working space look like?

I have a tiny studio in the city centre on the top floor of a strange schizoid building that’s split awkwardly between two takeaway restaurants. It’s very central but very quiet. During the COVID lockdown though I started working from home, and I’ve stayed here ever since. Again it’s a boxroom, but with a view of some trees instead of the back yard of a kebab shop.

Yours is the longest book on the longlist, and you’ve said in interviews that you always plan to write short books, but they just keep growing. In our age of diminishing attention spans, is it harder for long novels to keep readers gripped, or for authors to persuade publishers to publish them, and if so what’s your secret??

There’s a sense that a novel ought to come in at around 85,000 words, and it can definitely be hard to persuade readers to take on something longer. I’m wary myself of long books – it feels like such a commitment. But that’s an illusion. If a book is gripping, then you don’t care about the page count. Conversely, if a book is dull it will feel like a grind even if it’s only 200 pages.

That being said, I didn’t realize how long The Bee Sting was until I was about to send it to my editor, and I did expect some pushback. But she felt that the story had enough twists and turns to keep the reader engaged, and she didn’t want to cut purely for the sake of cutting. It was a real relief – another editor might not have been so brave. However I still dream of writing a 150-page, super-dense novella, like The Crying of Lot 49.

The novel brilliantly captures the frustrations of small-town life. How did you capture that small-town essence (not being from a small town yourself), and to what extent are the people and situations in the book based on real individuals or places? Also, how much of your own family is in the book?

I grew up in Dublin, but I have friends from small towns – a couple of my best friends married women from the Midlands, and it was the stories they told me that first got me thinking about setting a book there. Like everything in writing, it comes down to tiny details, the layout of the town, the phrases people use. ‘Well!’ is a big one in the Midlands. It’s how you say hello, but it’s often delivered in a tone of sardonic fatalism as if to suggest that there is no point saying anything more. Dublin itself can feel like a small town some of the time; you need to look elsewhere if you really want to disappear.

I didn’t put specific people or places in the book wholesale - typically real-life characters or situations never quite fit, no matter how perfect they seem. Instead it’s fragments of stories, bits of this character, that place. One true story I used though was the bee in the wedding veil – this happened to a friend of a friend on her wedding day, a bee flew into the car on the way to church and got trapped in her veil. But even there I had to change it – it didn’t work as a scene in itself, it had to appear as a yarn the townsfolk liked to spin.

I didn’t put my own family in the book, but my mother comes from a small town – near the border, not the midlands, and some of her stories showed up in a particular part of the narrative. Again, more to do with backdrop, ambience, then actual events.

The Bee Sting by Paul Murray

You’ve mentioned that Jonathan Frantzen’s The Corrections was an influence on The Bee Sting. Did any other novels inspire you – either in the way the book is structured, its humour, or certain characters?

William Faulkner’s novel As I Lay Dying was one of the first ‘grown-up’ novels I read. My mother gave it to me – I think there’s an affinity between that Southern world Faulkner describes and the part of the world she’s from. That was a major influence, tonally, and more so perhaps structurally, as he has the different members of the family taking turns to tell the story.

Who Will Run The Frog Hospital? by Lorrie Moore is a beautiful portrait of friendship, and I’m sure it informed the Cass chapters of the book. It’s very sweet and funny, which makes it all the more affecting when the darkness comes in; the contrast between that idealized friendship and the living compromise that is marriage, the urge at a certain point in life to swim back through the past to an easier time – Moore does all that so well.

The book has been described as ‘a novel about the past and our inability to ever outrun it’ - which could possibly be said of several other novels on this year’s longlist, many of which concern families navigating some sort of trauma. Is that how you would sum it up in roughly a dozen words? If not, how else?

That’s a pretty good description. Faulkner again has this fantastic line, ‘The past is never dead. It’s not even past.’ Time, the persistence of the past, these are things the novel as a form is very good at. That said, I really wanted to write about the present moment. Most of the book is set in the present, with all of its attendant terrors – the rise of fascism, the pornification of reality, the subordination of embodied experience to representations and so on. More than anything, I wanted to write about climate change. That sense of impending doom is something that feels different to the nuclear threat, for example, and gives a tone to the present that is new. Climate change relates to the past, obviously, but dwelling on its origins aren’t going to help us. We really need to find a new way of being to get through it and we haven’t found a way yet of doing that. In short what I’m interested is not so much the past coming back, but the ways it obscures the present and stops us from embracing the future.

Which book or books are you reading at the moment? In particular, are there any other Irish writers who you think deserve a place in the spotlight and haven’t had enough recognition?

I’m usually reading a bunch of things at the same time. Right now, I’m reading The Mirror and the Light – slowly, as I hate the thought of finishing it and having to leave that world. Before that I read Close to Home, Michael Magee’s brilliant West Belfast Bildungsroman. In terms of a place in the spotlight – well, there are so many outstanding writers working in Ireland at the moment. Soldier Sailor by Claire Kilroy is a novel about motherhood, and captures the chaos, exhaustion, and almost unbearable moments of joy so perfectly. It’s very moving, also very funny.

Do you have a favourite Booker-winning or Booker-shortlisted novel and, if so, why?

I loved Anna Burns’s Milkman. Again, we’re in West Belfast, this time at the height of the Troubles. The sense of paranoia and threat is overwhelming; everybody’s watching everybody else, friend and foe alike, and every word is scrutinised for hidden meanings, with the result that it becomes effectively impossible to speak – ‘whatever you say, say nothing,’ as Heaney had it. How can the writer convey a world that has made itself opaque? Anna Burns comes up with this ingenious solution whereby all of the names are removed, so it’s Somebody McSomebody, Maybe-boyfriend, Third Brother-in-Law, faceless figures circling each other in a bad dream. It’s gripping, tense, also very funny, as if Beckett had written a political thriller. It’s one of those rare instances of an experiment that pays off perfectly, and it was wonderful to see it win!

What are you working on next?

I’m halfway through a children’s book; I’ll try to finish that before starting another novel. I’m looking forward to just reading for a while, letting the grass grow, so to speak.

Paul Murray

© Cliona O'Flaherty