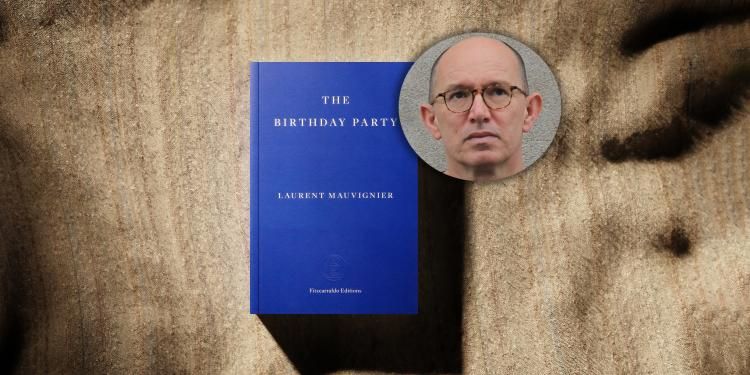

Daniel Levin Becker interview: 'I’ve never read a book like The Birthday Party'

Longlisted for the International Booker Prize 2023, translator Daniel Levin Becker talks about The Birthday Party in an exclusive interview

With The Birthday Party longlisted for the International Booker Prize 2023, its author talks about writing a novel in the vein of Stephen King, but with the language of Marcel Proust

Read interviews with all of the longlisted authors and translators here.

How does it feel to be longlisted for the International Booker Prize 2023, and what would winning mean to you?

I’m very happy and very proud. Authors need to have their work recognised beyond the borders of their own language, because in a sense that’s how their work becomes meaningful, when it emancipates itself from being read through a ‘national’ lens, which always locks the work into a certain setting, the ‘local colour’ aspect preventing it from touching on more universal questions. Winning this prize would mean that my book is able to share human issues common to all, beyond borders, that it can speak profoundly to anyone across the world, and that anyone, wherever they may be, can share in its concerns and, I hope, its emotions.

What were the inspirations behind The Birthday Party? What made you want to tell this particular story?

Initially, it was a script for a medium-length film that I wanted to direct. The film drew on the conventions of the home invasion movie. The more it seemed that the film wasn’t going to be made, the more I asked myself how a book could make use of the story, and with which literary methods. I told myself that literature, more so than cinema, could capture the span and the dilation of time, the psychological excavation of each character, the way that their pasts resurge in the narrative. In a nutshell: a novel in the vein of Stephen King… with the language of Marcel Proust (relatively speaking, of course!). I think it’s important to say that there are two films I very much had in mind: The Visitors, dir. Elia Kazan (1972) and Day of the Outlaw, dir. André de Toth (1959). And a few books, including Saturday by Ian McEwan, some novels by the Spanish writer Javier Marias and by the American novelists Cormac McCarthy and Joyce Carol Oates, as well as authors whose work on language nourishes my own writing, like the Portuguese writer Antonio Lobo Antunes and the Hungarian writer László Krasznahorkai.

How long did it take to write The Birthday Party, and what does your writing process look like? Do you type or write in longhand? Are there multiple drafts or sudden bursts of activity? Is the plot and structure intricately mapped out in advance?

This book was a very particular case, because it was the adaptation of a screenplay into a novel. I had the whole story and all the chapters. But I gave myself some constraints: each chapter had to be ten pages long. Sometimes there was a lot to say, so it went quickly; other times, very little, a character enters a room and just goes to sit down. But it had to be ten pages long. So I forced myself to accompany the character: it was a chance to get to know their past, their motivations, their way of thinking. I wrote a first version that was over 1,000 pages long.

Afterwards, I deleted a lot, pointless sentences, adjectives, etc. I didn’t remove any scenes from the book, but within each scene I cleaned up and slimmed down the text considerably. The book lost over 400 pages that way. I went over every word, at least ten hours a day for six or seven months. That was the rewriting stage. The actual writing would happen a few hours every evening. But the writing of the book occurred at a particular moment in my life. My son had leukaemia, and I was shut in with him during the day. It was before lockdown, but I was already in lockdown: I have to admit that I felt a real pleasure in the evenings when I left my own confinement by returning to these characters who were even more held ‘hostage’ than me. It took a year and a half.

Where do you write? What does your working space look like?

I’ve been writing on the same desk since childhood; I’ve moved 32 times in four decades with the desk! With regards to the rest, I need a wall in front of me, never a window, I can’t write if the view in front of me is too beautiful. I need earplugs to close up the space around me. What I want to hear is my breathing when I write, the rhythm of my sentences. I try to isolate myself not to block out external sounds, but to hear the phrasing; the inner, rhythmic life of each sentence.

Laurent Mauvignier

The book was the adaptation of a screenplay into a novel. I had the whole story and all the chapters. But I gave myself some constraints: each chapter had to be ten pages long

What was the experience of working with the book’s translator, Daniel Levin Becker, like? How closely did you work together on the English edition? Did you offer any specific guidance or advice? Were there any surprising moments during your collaboration, or joyful moments, or challenges?

Since Daniel lives in Paris, it was very easy for us to meet. Daniel sent me a few questions by email, to which I tried my best to respond. Sometimes these touched on very specific points and other times on more general questions. Daniel is also a poet, he’s a member of the Oulipo poetic movement, and his approach to language isn’t that of a translator in the traditional sense: it is also that of a poet who is sensitive to the musicality of the text, to the way in which the writing evolves from the start to the end of the book: at the start, the sentences are long and capacious and double back on themselves. As the book moves towards its ‘heart of darkness’, the language dislocates, deconstructs, falls apart. This movement was important to the book’s musicality, and Daniel understood that very well. Just as he understood that the dialogue (often the weakest part of a novel) was very important in creating the musicality and structure of a paragraph, even of a whole chapter.

Why do you feel it’s important for us to celebrate translated fiction?

Every language has its own spirit, and every nation has a unique literary practise: translation is a kind of safeguard of the teeming biodiversity of literature. Celebrating translated literature means celebrating alterity, diversity and abundance, and celebrating our own calling into question, the better to reinvent ourselves. Let us imagine for a few seconds a world where we can only read books written in our own language; a world where the only literary universes at our disposal come from inside our own languages, our own relationship to the world. It would undoubtedly be very limited and restrictive. How can literature truly come alive in us without seeing it transformed when we read totally different universes and approaches?

If you had to choose three works of fiction that have inspired your career the most, what would they be and why?

Light in August by William Faulkner, In Search of Lost Time by Marcel Proust and In Cold Blood by Truman Capote. Of course, it’s unfair and very difficult to discard so many books that have been just as fundamental as these three (I’m thinking of Conrad, Flaubert, Hugo in particular, so many others including the writers of the Nouveau Roman, Beckett, Duras, Claude Simon). But I chose these three titles because each one has built my relationship to my primary literary practise, which is novel-writing.

Faulkner taught me, in a certain way, to look reality in the face, to see that great art could be built from places and human experiences where literature doesn’t usually belong. It’s a question I often asked myself in my youth: how could I be a writer, I who come from a world that will never be spoken about?

From Proust, I learned deep immersion in the human spirit, its psychology and its depths, but also, and above all, the art of making the past rise up like a suddenly renewed and immediate image. Reading Proust made me want to find a language that unfolds its story within that infinity of factors which are the length and the dilation of time, and psychological analysis. It’s know as the Zeno paradox: the arrow approaches its target, and the closer it gets, the further away it seems. The more you get into the detail of a scene, the more closely you observe it, the more it seems immense and unattainable. What I owe to Proust lies in this feeling that writing a book, a scene, is to open up a vertigo; the infinite in a single detail.

Truman Capote’s book gripped me with its violence, but also – and above all – its analytical approach to the characters and to the situations. The novelist outlines a set of proceedings, and it’s the notion of process, of method, of analytical approach, that greatly, and increasingly, inspires me in my work.

Daniel Levin Becker