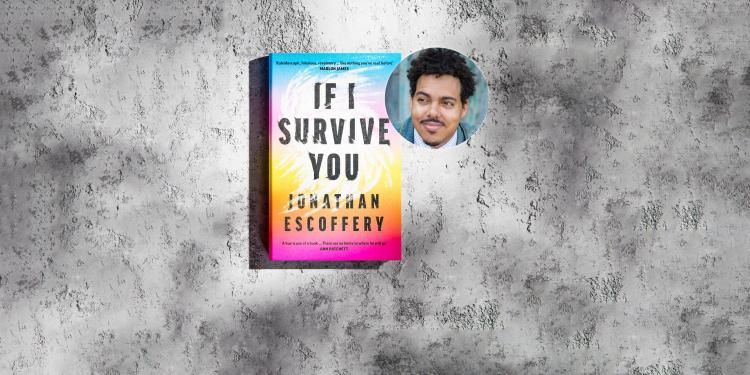

An extract from If I Survive You by Jonathan Escoffery

An exhilarating novel-in-stories that pulses with style, heart and barbed humour, while unravelling what it means to carve out an existence between cultures, homes and pay cheques

With If I Survive You shortlisted for the Booker Prize 2023, we spoke to Jonathan Escoffery about standalone stories, and exploring the fraught relationships between fathers and sons

Read interviews with all of the shortlisted and longlisted authors here.

How does it feel to be nominated for the Booker Prize 2023, and what would winning the prize mean to you?

It feels phenomenal to have the project I poured so much of myself into receive the global recognition that comes with the Booker Prize nomination. I think of If I Survive You as a transnational book, so acknowledgement from an organisation that honours fiction from all over the world feels particularly affirming. Seeing the communities I write about, especially those that have historically been treated as inconsequential, elevated to this level of visibility, is already an extraordinary win. Winning the prize would give this visibility longevity.

How long did it take to write If I Survive You, and what does your writing process look like? Do you type or write in longhand? Are there multiple drafts, long pauses, or sudden bursts of activity? Is there a significant amount of research and plotting before you begin writing?

It took approximately ten years to write If I Survive You, though there were many long pauses, as I moved homes frequently in search of ways to sustain myself and my writing practice. I don’t write much longhand, but I write a lot in my head and that’s what I did during those pauses. There were 50 or so drafts written.

I am always in the process of conducting research for my projects, though I do so during the writing process, and not necessarily beforehand. I write toward discovery and typically stop to plot out a story only when I feel particularly stuck, but find that looking back at what’s already on the page can guide me forward as well, because there may be a natural trajectory suggested in the early pages.

Where exactly do you write? What does your working space look like?

I prefer to write at my desk, on my desktop, to keep as consistent a writing habit as possible. My book was mostly written on my laptop, though, at my desk and at cafes and on trains, and in bed too. Wherever I work, I’m usually surrounded by stacks of books, some of which may have a tangential relationship with what I’m working on.

Jonathan Escoffery

© Cola Greenhill-CasadosMuch of the enjoyment of writing the book was in figuring out how to get my characters out of the trouble I created for them. Of course, in some cases, they don’t get out of it

If I Survive You has been described as a collection of short stories with an interconnected narrative, and as a novel-in-stories. How would you describe it, and why did you choose to write the book in this manner, rather than as a more traditional novel? Was it a conscious plan at the outset?

I knew from the outset that I wanted to structure it in such a way that the chapters worked as standalone stories, and the stories worked as chapters that built toward a larger narrative arc and toward a climax. I wanted to challenge myself, and thought this would be formally interesting, if not innovative, but I also suspect it closely resembles the episodic nature of human experience. It was when I stopped worrying about whether to label it as stories or as a novel that it finally came together.

As the title suggests, the book is ultimately a survival story. Trelawny and family are faced with constant obstacles – racism, Hurricane Andrew, the 2008 recession. As someone who, like the family in the book, also grew up in 1980/90s Miami, how much of the book is based on either personal experience or real people you’ve encountered?

I used some personal experiences and what I observed in the environment I grew up in as the backdrop and cultural context for the book, but I imagined my way into scenarios that dramatise issues my community deals with, while working to engage readers with every tool I had in my toolbox. I wanted the book to express emotional truths without limiting it to what literally happened, and much of the enjoyment of writing the book was in figuring out how to get my characters out of the trouble I created for them. Of course, in some cases, they don’t get out of it.

Much of the book is concerned with the question of identity. Trelawny, your focal character, is too white when in Jamaica, and too Black when in Miami. He longs for community among other Black people but never quite finds it. What made you want to explore the idea of belonging?

I’d say he’s considered too American in Jamaica, not culturally or phenotypically Black (American) enough in Miami, and too Black in the American Midwest. This answer is necessarily an oversimplification, which, in part, is why I felt the need to write an entire book about the nuances of identity and belonging. In part, this book was the result of my grappling with the question of who my protagonist is, or could be, recognising that there is a gap between the complex ways people discuss identity, especially where I am from (Miami), and many of the characters I had read about growing up.

If I Survive You by Jonathan Escoffery

The book’s serious subject matter – racism, poverty and prejudice – is tempered by humour throughout. Was this a conscious choice to help readers navigate potentially dark material? And does writing like this come naturally to you?

I agree that humour can help people digest material they might find uncomfortable – I think humour makes most reading more enjoyable. As much as I’d like to believe I can employ it at will as a strategy, I think that communicating through humour is a coping mechanism often used by people who are acutely aware of their relative powerlessness against systems that were designed to destroy them, and this is the mind frame we meet Trelawny in, and it was my state of mind while writing the book.

Many of the focal characters in the book are men. Black masculinity, fatherhood, complex father-and-son relationships and nuanced male emotions are at the heart of the book. What made you want to explore the male psyche and male relationships in this book?

I’m interested in what models we have for being good men, and in what potentially damaging messages we send men about how to be in the world, and in how those messages get passed from one generation to the next. I also wanted to explore the question of whether fraught relationships between fathers and sons can ever be repaired, and the associated costs of attempting to repair them.

Do you have a favourite Booker-winning or Booker-shortlisted novel and, if so, why?

I have a couple, but Marlon James’ A Brief History of Seven Killings brings together so many of the stories that I grew up hearing in my Jamaican household that I’d never seen elsewhere in literature. I remember streaming the ceremony when it won the Booker Prize and feeling such pride; it’s funny how someone else’s work can make you feel that. The book was also instructive formally in more ways than I can mention. It’s a natural predecessor of If I Survive You and the prize win made getting my book published much more possible. So thank you, Booker Prizes, and thank you to Marlon James.

Jonathan Escoffery

© Cola Greenhill-Casados