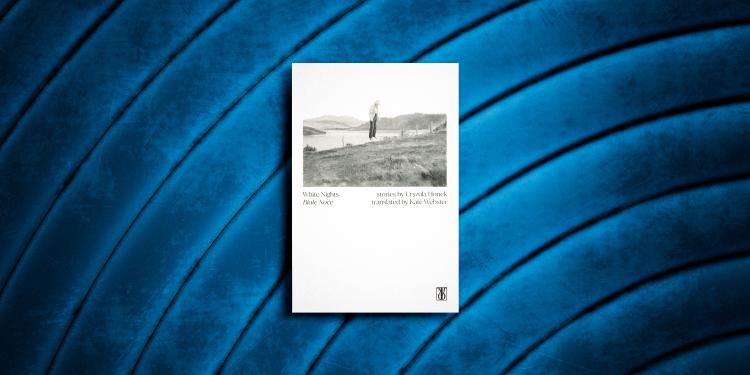

Reading guide: White Nights by Urszula Honek, translated by Kate Webster

A haunting series of connected stories concerning the tragedies and misfortunes that befall a group of people in a village in Poland’s Beskid Mountains

White Nights, originally written in Polish, is longlisted for the International Booker Prize 2024. Read an extract from the first story in the collection here

White Nights is a series of thirteen interconnected stories concerning the various tragedies and misfortunes that befall a group of people who all grew up and live(d) in the same village in the Beskid Niski region, in southern Poland. Each story centres itself around a different character and how it is that they manage to cope, survive or merely exist, despite, and often in ignorance of, the poverty, disappointment, tragedy, despair, brutality and general sense of futility that surrounds them.

A house like a chicken coop, so that if you leaned on it or kicked at it, all the planks would fall to the ground, and some would break in half, everything rotten. How it didn’t collapse on their heads over the years, I don’t know. Maybe they walked on tiptoe and didn’t cry out when they fucked, or when they had bust-ups, otherwise I don’t get it. Plus the house sits on the very edge of the hill, right next to the turn-off to Rożnowice. If you drove past in a lorry, you could high-five Pilot as he leaned out of the window. Everything inside must have been shaking when they were eating or sleeping, I wouldn’t have coped with it for that long, but what can you do if you’ve got no choice? And there was just the one main room, plus a kitchen and the crapper outside, and twelve mouths to feed – well, eleven and a half, cos Pilot only counted as half. Did I use to go there? Not much, only once or twice when I was little, Pilot and Andrzej would come to ours, or more often we’d play in the field, in the scrubland or Grodzki woods. But there’s one time I was there, I remember it, and I was maybe five years old. The entrance was more like a shed than a house, dirt beneath your feet, straw poking out from the walls and hanging from the ceiling, the plaster flaking, but that’s not what I remember most. The first time, I was scared of the dark, cos you entered in broad daylight and in there it was night, no windows in the hallway, only in the kitchen opposite, but it seemed distant and bright, like it wasn’t part of the house. I don’t know if that was all real, but I reckon I was onto something. Now it seems to me that when my time comes – and I’m the only one left of the three of us – I’ll walk down that hallway to my end.

Maybe if Pilot hadn’t been so hung up on that pond and that girl, he’d still be here.

Urszula Honek

The sun goes down gradually here, it’s not like you count to three and it’s suddenly so dark you can’t see your hand in front of your face. To begin with, the trees disappear into the gloom, then the roofs of the houses, the windows, the people, and finally the cows in the fields. The world turns red like it’s caught fire. You fear it slightly, but then a deep blue starts to show through, trying to extinguish the flames, steadying the heart. Every summer here starts and ends like this, unless it’s pouring with rain, then it’s ashen, as if people had taken dust from the coal wagons and sprayed it into the air, that’s how I’ve imagined it since I was a kid. When it’s pouring, sometimes storks come out onto the waterlogged meadows and sink their skinny legs in so deep that they can’t move, it’s a funny sight. The foxes – I like them the best – are keener to stick their heads out of their burrows, and by day they start toing and froing like taxis in the city centre. The redness confuses the humans more than the animals, they look up at the sky more often than usual, then clench their fists and keep walking, but if you stopped them and asked: “Where’d you go?”, they couldn’t tell you. They’d just stand there, like they’d been roused from a deep sleep, their mouths open. On days like that, Pilot would go up the hill with a shovel and see where he could start digging. He’d stand still in the red landscape and crane his neck.

He started from the north.

“I’ll get going on the pond from the edge of Firlit’s field,” he said suddenly outside the shop, with his frog-like cackle.

Nothing else, just that one sentence. His head was usually tilted backwards, but when he laughed it looked like he was about to fall over, cos his head went even further back, almost as far as his arse.

“Hey, Pilot, you’re fit for the circus, you could do backwards somersaults,” people would say, and I don’t think he realised they were taking the piss out of him.

At one point, I even saw him practising fucking gymnastics! Not as a child, he was already getting on a bit. I dropped round cos he hadn’t been at the shop for a few days, and he was usually there day in, day out, but his front door was closed. So I looked in the shed and there he was, touching his toes and doing star jumps. I was speechless. Had he been hiding away since he was a kid and dreaming of running off to join the circus? Of course, we all have dreams, but he’s quite skinny, a bit of a runt, and not too agile. He could dig wells, I’m not gonna lie, he got work when he wasn’t drinking, and there’d been no complaints there, but he wasn’t cut out for acrobatics. When he jumped, his feet barely left the ground and he fell over seven times out of ten. I stood there and I couldn’t stop watching him, one minute I wanted to laugh, the next I wanted to cry, it didn’t make sense.

The entrance was more like a shed than a house, dirt beneath your feet, straw poking out from the walls and hanging from the ceiling, the plaster flaking, but that’s not what I remember most.

The first time that happened with him – that I was sad and happy all at once – was when we were little, maybe in the second year of school. Sometimes he went to school, but more often he didn’t, he wouldn’t show up for weeks, then he’d come back for a bit, he never learned to read well, could barely write his own name. Since Andrzej and I were his closest friends, the teachers asked us: “Where’s Mariusz?”, cos that was Pilot’s name. But we just lowered our heads and shrugged to say we didn’t know – and that was the truth. We thought his folks had put him to work and weren’t letting him go to school, but it turned out that wasn’t it. He left the house every day, slinging his bag over his shoulder, even saying “go with God” to his mother, cos that’s what everyone here was taught to do, but he didn’t make it to the school gates. Instead, he lay in the ditches for six or seven hours, or hid in the bushes, and when word got out, he came to school black and blue. I don’t think his folks had ever beaten the shit out of him like that, though they did beat him regularly. And when someone asked why he’d been gone for so long and where those bruises and scabs had come from, he’d say that he’d gone to war, he was guarding the trenches, darting around the forests with the partisans. And that was the first time I got tears and laughter together. And now I wonder whether maybe he wasn’t making it up, maybe he really had seen war, defended his homeland, and shot at the enemy for his mother and father? Who the hell knows. I’ll be honest: I lived in Germany for a few years, and everyone knows they made lampshades from human skin, but still, people like Pilot are respected there now, welfare, nurses, clean hospitals, scented toilet paper, and the kind of sick pay where you don’t need to do anything ever again. That’s how it should be here too, not just all hype and no action. That kind of illness is even worse than when you’ve lost a leg, cos you can’t see it, they’re just plodding along, but they feel like they’re flying above the earth. Pilot had always been like that, he’d suddenly stop talking and just stare into space. You could talk to him, but by that point he’d flown somewhere far away and he seemed to feel better there, cos for a long time he wouldn’t want to come back. But when he said he was going to dig a pond, he laughed, and louder than usual, right from his core, like his insides were shaking. I’d only heard him laugh like that once before, twenty years earlier, when I let him ride my motorbike. At the time, his reaction surprised me, but now that I’m older and the lads are gone, I get it. So when he’d said about the pond, he fell silent, stared into the distance, then got up and left without a word.

He started digging on the most beautiful morning.

Kate Webster