Q&As with the 2021 nominated authors

Read our interviews with the nominated authors for this year’s Booker Prize

Q&A

'I have always had a problem with people who talk about Africa as though it is a country'

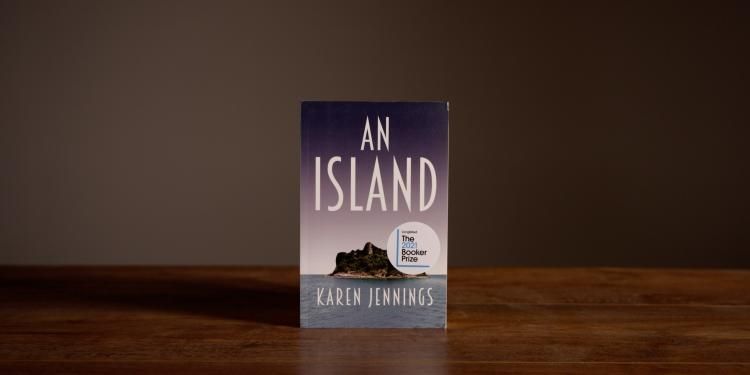

Karen Jennings speaks to us about why she’s uneasy with the term ‘literary canon’, and what she wanted to examine in her Booker Prize-longlisted An Island.

How does it feel to have An Island longlisted for the Booker?

I am not quite sure how to answer that because the truth is that after the initial surprise, well, then life just carries on as before, but now with a lot more emails to respond to! However, I am absolutely delighted for my publishers (Holland House in the UK and Karavan Press in South Africa). Both are small publishers – in fact, I’ve seen them referred to as micropublishers a few times – and it is so often the small publishers that are the ones who are willing to take the risk and to publish something that they really believe in. It is wonderful to see them getting recognition.

Which authors have influenced or inspired your own writing?

This is always an impossible question to answer. I have been influenced by a variety of authors and genres over the years, but I suppose my most enduring interest has been in social realism and in poetry.

What is your favourite Booker-winning or Booker-shortlisted novel?

I don’t necessarily have a favourite, but I will say that about 3 or 4 years ago I came upon a slim book in a second-hand bookshop. I read it, loved it, and have read it several times since then. That book is A Month in the Country by J.L. Carr. I thought I had come upon a secret gem. Only recently did I discover that it is a much-admired novel and that it was shortlisted for the Booker, in 1980 I believe.

What are you working on next?

I have a manuscript that I finished in 2019 and an unfinished manuscript in a drawer or box somewhere (I write by hand). The 2019 manuscript is with my agent (I just recently signed with Lucy Luck of C&W). The unfinished manuscript will have to wait. I need to do a bit more research and think a bit more before I feel confident that I can adequately engage with the subject matter. Other than that, I have begun a PhD in history this year, so writing my thesis must be the priority.

Your story takes place on a small island over four days but manages to encompass an entire lifespan and to suggest the politics of a number of possible nations. How did you formulate, and achieve, that ambitious combination?

I wanted to try to understand and engage with a number of very complex issues and was wary of doing so in a heavy-handed fashion. I decided that the best approach for me would be to simplify the story as far as possible, much as one might see done in a poem. By choosing a small location, and limiting the number of characters, even limiting the possibility of conversation, I felt that I could best serve the topic. It was not easy. In fact, I remember very little about writing this book other than walking the dogs every morning and muttering to myself, almost as a chant: ‘This book is going to kill me, this book is going to kill me.’

Samuel has been on the run from colonisers, spent time on the streets and decades in prison. Now he lives alone on an island. What did you want to examine through each of those difficult circumstances, or through the concatenation of them?

I wanted, in part, to try to understand what impact socio-political events and the legacy of those events might have on an individual. Samuel is not a good man, nor is he a bad man. He is simply ordinary. How has the past imposed itself on him? How does it make him feel about who he is and what his place in the world is?

The stranger who washes up is tied to an oil drum. Is Samuel repeating the colonisers’ actions in relation to this migrant?

In Samuel’s behaviour we see, on the small scale, how xenophobia might be kindled. The way in which the threat of the outsider makes him think and behave in order to protect what he considers to be his own. This is, sadly, a universal topic.

Neither the island nor the country is ever named. Did you have somewhere in mind?

I have always had a problem with people who talk about Africa as though it is a country. I bristle when people say things like, ‘I went on holiday to Africa’, as they are clearly unaware or unwilling to acknowledge that Africa is a vast continent with many different countries and cultures. When people speak of Africa in this way, my mind always immediately goes to the Scramble for Africa. There’s a famous cartoon in which Africa is depicted as a cake, being sliced up and doled out to various European leaders. Though it might seem counterintuitive, this was part of what motivated me to “reduce” Africa in my novel. I wanted to go back to that cake, to those leaders, and to explore what the long-lasting effects of the Scramble for Africa might be. Since the Scramble affected all of Africa, this story might well represent similar experiences in a number of countries. I wanted to examine what the consequences of the Scramble might end up being for an ordinary African man today.

There is something almost mythical about this setup. Are there particular works of literature you feel it’s descended from?

As an undergraduate and also as a postgraduate, I was very taken with Ovid’s Metamorphoses. I was rather obsessed with it, in fact. I can imagine that text having had an enormous impact on me, though not necessarily consciously.

Is there, in your view, such a thing as a Commonwealth literary canon or culture, and if so, what would it comprise?

I become uneasy when I hear the words ‘literary canon’. Who decides what is important and meaningful? There can be nothing so finite without excluding the various experiences and interests of millions. Why promote such alienation?

Karen Jennings. © Carol Coelho