Interview

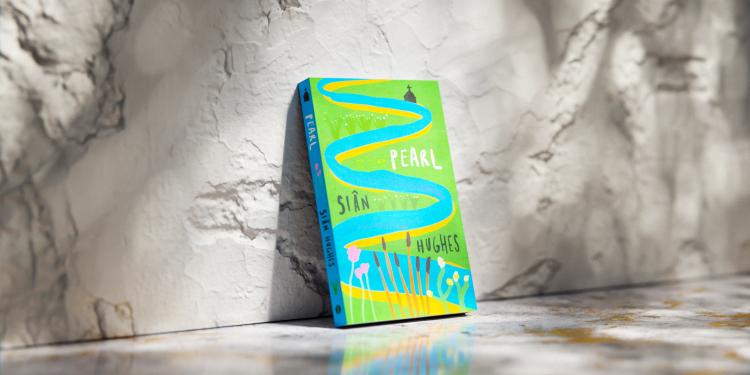

Siân Hughes contemplates both the power and the fragility of the human mind in her haunting debut novel, which was inspired by the medieval poem of the same name

Marianne is eight years old when her mother goes missing. Left behind with her baby brother and grieving father in a ramshackle house on the edge of a small village, she clings to the fragmented memories of her mother’s love; the smell of fresh herbs, the games they played, and the songs and stories of her childhood.

As time passes, Marianne struggles to adjust, fixated on her mother’s disappearance and the secrets she’s sure her father is keeping from her. Discovering a medieval poem called Pearl - and trusting in its promise of consolation - Marianne sets out to make a visual illustration of it, a task that she returns to over and over but somehow never manages to complete.

Tormented by an unmarked gravestone in an abandoned chapel and the tidal pull of the river, her childhood home begins to crumble as the past leads her down a path of self-destruction. But can art heal Marianne? And will her own future as a mother help her find peace?

If you head out of our village down the lower road to the old watermill, you come alongside a row of dark ugly ponds we called the pits. They are surrounded by trees, some half-fallen in, and the surface is greasy with dead leaves. When I first learned to ride a bike we would come along here, my mother in front, going very slowly to allow me to keep up. She had to keep looping back or wobbling into the middle of the lane to wait for me. When we came to the pits she would cycle on the wrong side of the road, far away from them. It didn’t matter. There were hardly ever any cars.

Every time we went past she would tell me the place was haunted, which was why she kept as far away from the water as she could. She told me how, years ago, a beautiful girl was walking home along this lane after the Wakes, and a young boy followed her, perhaps, some say he did, some say he didn’t, and she was found drowned in the pit. The reason it was haunted was he was never punished. No one was punished. So she can never be at rest.

And then further on down the lane my mother would loop back around on her bike and cycle alongside me and say, perhaps they were punished, in the end, because that man grew old in a cottage not far from our house, and by the time he died the whole place was grown over with hawthorn like Sleeping Beauty’s castle. Those creepers worked their way into the windows and doors, wrapping themselves around the porch so it fell away from the front of the house, the garden a mass of thorns you had to cut your way out of. Nothing would stop those thorns from growing stronger and stronger the more you cut them.

When the old man lay dying he called for his brother, claiming that he had something important to say, and the brother had to take a ladder and lean it up to the bedroom window to hear him because his wife never would let him in the door, but it was too late. And all the years he lived in that house with his wife there was never a child. Not one.

I knew she meant the thorns were the dead girl come back to find him, they were her fingers climbing into him, breaking down the mortar and sucking the life out of the house, that it was the dead girl who stopped the babies from coming to that house. I asked her, had she seen the house with the creepers, was it still there? She said, yes, we go past it all the time but you would hardly notice it now it is so fallen in and grown over. The garden is full of rhubarb and raspberries gone to seed, and some people go in through where the hedge is collapsed and help themselves. I would never go in it myself, she would say. I would never SET FOOT.

Siân Hughes

I realised that almost any physical symptom could now be attributed to my mother’s disappearance. Headaches, sickness, sleeplessness, sleepiness, dirty fingernails, eczema patches, a snotty nose, tooth decay, unbrushed hair, nits

I was terrified of the pits. Each time we cycled past I would imagine the girl floating in the water, her long dress ballooning out, her poor cold feet sticking up out of the water all yellow, her face hidden in the peaty scum. I could barely keep my eyes looking straight ahead, and drifted out into the middle nearer to where my mother cycled along the opposite ditch. Sometimes she would let me hold on to the rack on the back of her bike and be pulled along and out under the trees that closed over the lane, away from the darkness and coldness that belonged in that place.

When did they first tell me they thought she had drowned? Not right away. Weeks certainly, maybe months after she stepped outside. I didn’t believe them. I said, ‘No! She always cycles on the other side of the road, she would never SET FOOT. She hated that place, where the girl drowned.’ And all the time I was saying, ‘No, no, no!’ it sounded to me like my voice was going further and further away, smaller and smaller into the distance until I was shouting silently into a long thin tube. All around the tube was darkness, but at the end of the tunnel was a bright, lit circle of water with a girl lying face down in it.

I didn’t know that I was passing out. I had heard the word fainting. But no one had ever described what that might feel like if it happened to me. I thought this sudden loss of hearing down to the most distant whisper, this reduction in what I could see to a small faraway circle, were permanent losses. I thought in that moment that I would never again see or hear anything the way I used to. And in a way I was right.

I blacked out onto the stone floor in the kitchen, knocked out the last of my milk teeth, and gave myself mild concussion. I was glad of it. It stopped them talking about the water, for one thing. And I very quickly discovered that this was a way to avoid going to school. Each morning I was asked if I still had a headache. If I had a headache I was allowed to stay in bed and eat Marmite sandwiches and leave the crusts and draw pictures and look out of the window.

After a week or so the doctor came to visit me. He said it was unusual for someone my age to still be suffering from concussion after this long. That maybe I ought to go for an X-ray. That I had no other symptoms, no dizziness or sickness, but that maybe they ought to check. He said all this to my father in the doorway, and so handed me some useful weapons in my fight against school. Dizziness, sickness. When I ran out of headaches I tried these out. I was too cunning to use the doctor’s exact words. I experimented with different ways to describe dizziness. ‘I feel like I am on a roundabout and I can’t get off,’ or ‘Everything spins around me.’

Mostly Edward shrugged and said, ‘Me too, sweetie,’ and let me lie in bed. I realised that almost any physical symptom could now be attributed to my mother’s disappearance. Headaches, sickness, sleeplessness, sleepiness, dirty fingernails, eczema patches, a snotty nose, tooth decay, unbrushed hair, nits. Especially nits. Nothing was off limits.

Around the time I passed out on the kitchen floor Lindsey came to look after Joe every day so Edward could go back to work. If I claimed to be ill, all he had to do was tell Lindsey I was staying home, and get out of there.

I adored Lindsey. She painted bright colours on my chewed fingernails. She let me stroke her fluffy yellow jumper. She brushed my hair so much it stood up in static fluff, and tried to plait it flat. She didn’t try to tell me freckles were beautiful, or that my hair looked nice. She said, ‘You can put on foundation when you’re older, if you want. Some highlights might help.’

She kept the electric fire on all day, and the television, and she didn’t mind how many times Joe watched the same episode of Thomas the Tank Engine. She made us things to eat out of cardboard boxes in the freezer. She read my horoscope in her magazines and it was always about boyfriends. She talked to her sister on the phone for hours with the receiver tucked between her shoulder and her ear while she carried Joe on one hip. She was so skinny his legs wrapped right around her. She smelled of Dolly Mixture and apple peel. Any time she put Joe down he cried, so she carried him around all day. She could put makeup on with one hand while Joe balanced on her waist. She let him hold the little tubes of paint for her. She had a special brush for putting powder on her face and she tickled my nose with it.

If I drew her a picture she said, ‘Oh, you are good with your hands. I bet you got that from your mother, bless her.’ I don’t think my mother ever drew or painted, but I took the compliment anyway. I liked to get her talking about my mother, even though she’d never met her. I would bring her random things from around the house and say it was my mother’s favourite, or that she had made it, or found it in the garden. Half the time I made it up.

When the school attendance lady eventually came round I was lying on the sofa in my pyjamas watching Pigeon Street on our new television eating sliced-bread sandwiches with ready-sliced cheese. The attendance lady was dressed head to foot in shiny brown things. Shiny brown shoes, shiny pale brown tights, a shiny brown polo neck jumper, a shiny brown skirt that creaked. I guess it must have been leather. I had never seen anything like it before. Lindsey tidied up an armchair and offered her tea. Lindsey asked how she liked her tea. I answered for her. ‘Brown,’ I said. ‘She likes her tea brown.’ I thought this was quite funny.

The brown lady opened her shiny brown handbag and took out a notebook and pen. ‘So,’ she said, snapping the bag shut again, ‘I understand you recently lost your mother. Is that right?’ It was perhaps the first time anyone described it that way. I had carelessly, foolishly, lost my mother. I had failed to keep hold of her and let her slip away. I had been playing a game in the garden with her, and forgotten where I put her. I had stopped thinking about her for a minute, then remembered too late.

I realised now why the police had asked me so many questions. Where had I been, what had I been doing, what time was it when? All the questions you ask someone who has lost something. Where did you last see it? Did you take it outside with you?

It was one of the things that maddened me about my parents. If I said to either one of them, ‘I can’t find my shoe,’ or teddy or cardigan, they would say, ‘It’s exactly where you left it.’ If pushed, Edward liked to say, ‘According to the laws of physics, Marianne, matter can be neither created nor destroyed. It has therefore not disappeared from the face of the earth.’

I narrowed my eyes at the brown lady, and concentrated on not crying. I tried hard to rub out the picture in my head of my mother saying, ‘Think, Marianne! I must be exactly where you left me. Where did you leave me this time? Where could I be? Have you left me in the garden maybe?’ I swallowed hard and said, ‘According to the laws of physics, matter can neither be created nor destroyed.’ I kept staring at her very hard to prove I was not really crying even though my face was quite wet.

She looked at me a long time before replying. What she said was, ‘What are you reading at the moment?’ As if everyone over the age of six is reading something at the moment. I was having a lot of trouble reading, so I told her the last thing I remembered reading when my mother was there. The Fall of Jericho. The army marched around and around the walls, with their feet keeping perfect time, until the walls simply crumbled. She asked me if I thought that really happened. And I said, yes, why not? How else do you get the walls around a city to all fall down?

‘Oh, I don’t know,’ she said, ‘maybe some kind of explosive?’ I quite liked the brown lady after that. Which is a good job, as she came to visit me a lot.

Pearl by Siân Hughes